When biologists refer to the 'wild type', we mean that there is a dominant phenotype or trait that most organisms in a species possess. For example, most Drosophila melangaster (the fly commonly used in genetics) have red eyes--red eyes are the wild type, while white eyes are often referred to as the 'mutant' phenotype.

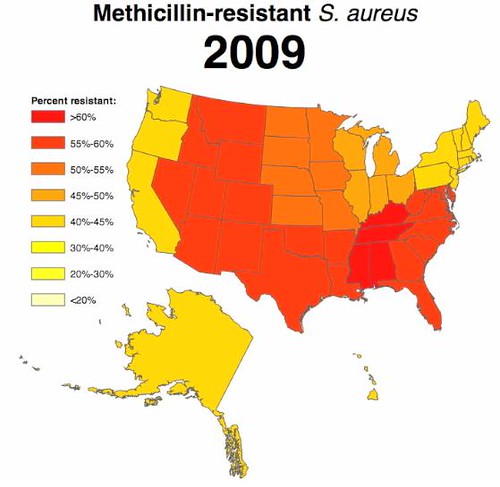

If there's any good news about antibiotic resistance, it's that the wild type regarding resistance among commensal bacteria (those that live on and in us and that don't typically cause disease) is still sensitivity to antibiotics, not resistance. Only 1.6% of Staphylococcus aureus (the "SA" in MRSA) isolated from healthy people are resistant to methicillin (although this is an increase from 0.8%). But those S. aureus isolated from diseased patients are very different. Here's what clinical isolates of S. aureus look like at the state level in 2009:

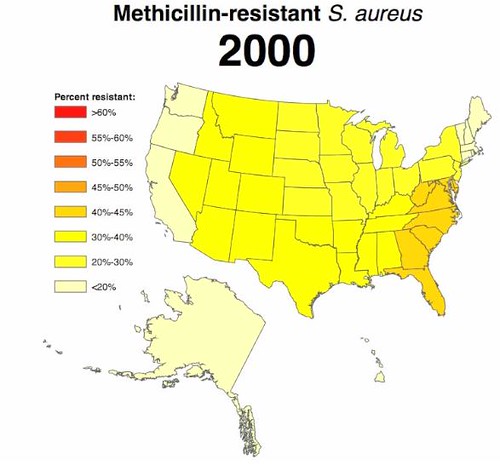

By contrast, here was the situation in 2000:

At this point, in the hospital, resistance in S. aureus is the wild-type.

An aside: For reasons that aren't obvious to me, Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi always seem to do the worst for every drug resistance that CDDEP maps. Any thoughts as to why?

Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi have the worst health in the U.S. The people are already battling obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and a ton of other factors that make them more susceptible to all infections. Antibiotic use in these states is high for many reasons, so resistance develops. I think it's just a consequence of overall health in these states being absolutely horrible.

How Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus spread World wide

Uncontrolled prescription of broad spectrum antibiotics made organisms to resist it.So a secondary infection by S.aureus course serious condition.

So, if the current trend continues (are there resons to think it won't?), how long until all S. aureus (at least in the U.S. clinical setting) is methicillin-resistant?