This article is reposted from the old Wordpress incarnation of Not Exactly Rocket Science. The blog is on holiday until the start of October, when I'll return with fresh material.

You don't normally hear continents described as speedy, but it's now clear that some are much faster than others. India, in particular, is the Ferrari of continents and now, scientists have discovered why.

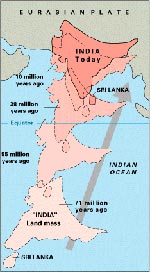

Rewind 150 million years and the Earth looked very different. Most of the land in today's southern hemisphere were united in a single super-continent called Gondwana, including Africa, Australia, South America, Antarctica, India and Arabia.

Rewind 150 million years and the Earth looked very different. Most of the land in today's southern hemisphere were united in a single super-continent called Gondwana, including Africa, Australia, South America, Antarctica, India and Arabia.

The Earth's crust is not a stationary shell but an ever-shifting mosaic of tectonic plates that constantly (albeit slowly) reshape the face of the planet. Underneath the crust lies the much hotter mantle, and plumes of super-heated rock occasionally erupt out of this layer, causing hotspots of volcanic activity.

Geologists believe that a particularly large 'mantle plume' kick-started the break-up of Gondwana. Now, Prakash Kumar and colleagues from the National Geophysical Research Institute in India have found that the plume also gave India a turbo boost.

Thirty years ago, Tom Jordan discovered that the old continents have thick roots made of light and buoyant material that extend deep into the mantle, like the keels of ships. Now, Prakash suggests that the plume that broke up Gondwana also melted off most of India's roots, turning it into a free-floating raft among strongly anchored peers.

Thirty years ago, Tom Jordan discovered that the old continents have thick roots made of light and buoyant material that extend deep into the mantle, like the keels of ships. Now, Prakash suggests that the plume that broke up Gondwana also melted off most of India's roots, turning it into a free-floating raft among strongly anchored peers.

Prakash used a new technique developed by German scientists, called the 'S-wave receiver function', to measure the depth of these continental roots with unprecedented accuracy.

Using seismic measuring stations dotted all around the southern hemisphere, they showed that the Indian continent is surprisingly thin, extending a mere 100km into the mantle. The other continents go much deeper - Australia's and Antarctica's plates are up to 200km thick, while Africa's roots extend for 300km at their deepest point.

It wasn't always that way. Earlier studies have shown that India's rocky roots are rich in diamonds, and these typically form in deep roots, some 140km below the crust, and migrate upwards. Their presence underneath India suggests that its roots used to be much deeper, leading Prakash to suggest that they were melted away by the plume that split Gondwana.

This process greatly speeded up India's movements, giving it a top speed of 20cm per year. That may not seem like much, but it's considerably faster than Africa and Australia, which move at about 2-4 cm per year, or Antarctica, which is relatively stationary. If we sped these other continents up to the pace of an Olympic sprinter, India would be zooming past at sports car speed.

This process greatly speeded up India's movements, giving it a top speed of 20cm per year. That may not seem like much, but it's considerably faster than Africa and Australia, which move at about 2-4 cm per year, or Antarctica, which is relatively stationary. If we sped these other continents up to the pace of an Olympic sprinter, India would be zooming past at sports car speed.

As it drifted upwards, it crashed into Asia at geologically break-neck speed, crunching the land at the collision zone and creating the largest and tallest mountain range on Earth - the Himalayas

More geology:

- Megaflood in English Channel separated Britain from France

- Bleached corals recover in the wake of hurricanes

- Blood Falls - bacteria thrive for millions of years beneath a rusty Antarctic glacier

- Climate scientists recruit elephant seals to study Antarctica's waters

- Snow-making bacteria are everywhere

Reference: Kumar, Yuan, Kumar, Kind, Li & Chadha. 2007. The rapid drift of the Indian tectonic plate. 2007. Nature 449: 894-897.

"a free-floating raft among strongly anchored peers"

Has that statement been pier reviewed?

:D

Mr.Prakash Said depth of the root is 100 KM how about Eurasian plate

if the Indian plate is free to float on the mantle why it was not moved in another direction instead of NE direction towards Eurasian plates?

dose the magnetic record is available for the Indian Plate?

regards

siva

Wow, that is fascinating. I can't wait to show this to my children.

The title is misleading, since India is not a continent.

Huh! I find it interesting that this might imply the Himalayas are unique in the history of the planet, since they required such an unusual set of circumstances.