One of the things I always wondered was why Galileo's Eppur si muove! (And yet, it moves!) was such a big deal. Yes, he was talking about heliocentricity, and the Earth moving around the Sun instead of the other way around.

But I was a little bit puzzled. Why, after all, would the Earth moving be such a revolutionary idea? Every night, if you look up and watch the skies over time, you'll see something like this:

The sky rotates! Not only do the stars in the night sky rotate, but the Sun's path through the sky also goes along one of the same paths that the stars do, as does the Moon. (For a spectacular video, go here, or here for my writeup of it.)

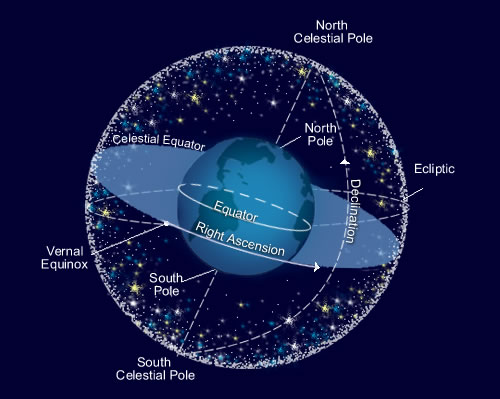

So, it always seemed to me that there are two possible explanations for this observed phenomenon. The first one is that the entire sky -- everything in the heavens above the clouds -- is rotating once a day. The ancients thought of this as a "celestial sphere", thinking that everything in the heavens was on a huge, fixed sphere that rotated once a day.

But the second possibility is that the Earth is rotating, and we only see the heavens appear to rotate because we, ourselves, are on something that rotates. In fact, if we define our rotation as clockwise, we will see the heavens appear to rotate counterclockwise. (This is a large image, I know.)

So, why was "eppur si muove" such a big deal? Didn't we know about this second possibility? Didn't people at least consider it?

The answer, shockingly, is no, not really. Why didn't we consider it? Because looking up and noticing that the heavens rotate predated our idea that the Earth could be round. If the Earth is flat, then it wouldn't make sense for it to rotate, would it?

The huge mistake is that once we discovered the Earth was round (in about 300 B.C., by the way), we didn't reconsider this problem. We didn't go back and say, "Hey, you know what? Instead of this celestial sphere idea, maybe it's just us that's spinning!" And so we held onto the idea of a fixed Earth for nearly 2,000 more years.

I can't help but wonder, if we went back and critically re-examined our assumptions and conclusions based on what we know now, if we would uncover some fantastic possibilities that could challenge our current scientific views of the Universe? Or, if everything we have concluded to this point really is the scientific best we can do with what we know?

Actally, a Greek philosopher, Aristarchus of Samos, hypothesized a heliocentric solar system shortly after the earth was found to be round.

well, i suppose it could *actually* be turtles all the way down...

:)

Nicole Oresme (1323–1382) considered the proposition that the Earth rotated on its axis, producing the apparent motion of the skies.

The idea was so revolutionary because it meant, for the first time, that mankind wasn't the center of creation. That's why it was so hard to accept, especially in the Monotheistic world. The idea that the universe exists with earth simply one of the players, and not in the leading role, was almost unthinkable. If god made us on the sixth and final day, and no less than in his own image, why would he put us anywhere but in the center? It was an affront to God to think else.

You had to be very original, and to be born at the right era (after the peak of the renaissance, with it's humanistic ideas), to be able to see things differently. I'm sure we have our own paradigms, and that some Galileo or Einstein will come along one day and shatter them to bits. Most of us are thinking "Light Speed" or "Time Travel" as options for revolutionary thought. The only thing is, we won't know what will be shattered until it's done - because right now we're so convinced the thing is true, we're not even thinking about it.

The same thing happened to physicists in the last century.

They initially believed that fission of uranium was impossible based on the plum pudding model of the nucleus. After they adopted the liquid drop model of the nucleus, they continued believing that fission was impossible in spite of the fact the liquid model made it fairly easy to explain fission. That's why it took a chemist to solve the problem!

A slightly similar thing is happening now in enzymology and structural biology. Namely the biochemists are starting to actually *learn* about Quantum, and using it to explain the models, rather than just using it as a catch-all explanation for why their models sometimes don't work.

Well, isn't that essentially what a big part of science is? Taking new discoveries and then reapplying them to old theories to see if the theories still stand up? I guess the question is really are there any major theories that we have yet to go back and test based on what has been discovered in modern times. With all of the PHD candidates doing all that they can to try and come up with that "original idea" I am betting that there are plenty of people doing a pretty good job finding old theories that can hopefully be proven wrong.

Edit to above post: (I wasnt finished yet)

I certainly hope that isnt the case though. Proving old theories wrong is one of the most exciting things. The media brings it up in headlines quite often but it is so rarely the case that an strong theory was proven to be incorrect. Most often it is just some crackpot who was recently abducted by aliens pulling some data out of his behind.

Recall that during the previous century Martin Luther initiated the Protestant Reformation, and then Henry VIII (who had been granted the title "Defender of the Faith" for his critique of Luther) split off the Church of England in order to divorce his wife. By the early 17th century the Catholic Church felt quite vulnerable, and they were worried (with some justification) that if Galileo's ideas became widely accepted it would be a threat to their own authority. Somewhere along the line Galileo managed to antagonize the wrong person, who sicced the Inquisition on him. That would be the same Inquisition that was busy burning heretics and witches all over Europe.

I'd say the simplest explanation is that we naturally view the ground beneath us to be fixed and (mostly) immovable -- to consider it moving or rotating contradicts our immediate experience. Knowing nothing else, if the ground I'm standing on seems to be motionless, and the stars overhead appear to be moving, it seems pretty straightforward to assume that they're moving, not me.

I always thought that the "and yet it moves" comment was a reference to the Jovian moons. Galileo spotted the Jovian moons moving night after night through the telescope, apparently rotating about Jupiter. I don't know much about Galileo's personality, but I imagine the first scientist to see this would be very excited to share the news. This would have been an awesome wonder to experience, and to realize what it meant.

A smaller version of this wonder would be Rutherford detecting electrons bouncing back from gold foil.

tedd

Aristarchus, who was mentioned above, was used by Copernicus to give credence to his ideas, since authorities were heavily relied upon by academics at that time.

And really, Copernicus' idea wasn't really persecuted at first, especially since there wasn't any deciding data to confirm it. Had Galileo been more diplomatic (and hadn't had a seriously flawed argument for heliocentrism in his book), it's possible he would have fared better as well.

But aside from authorities like the Bible and Aristotle (who mattered far more to scholastics of the time than did Aristarchus), there were before Newton seemingly important objections to heliocentrism. What keeps the earth revolving, for instance? Why don't we experience gale force winds, as the earth whips around rapidly (like the earlier objection, the answer hinges upon conservation of momentum)? Why don't we feel the earth moving? Why don't we see parallax of stars (could they really be that far away?)?

Without good answers to the objections, Galileo seemed to many to be altogether too arrogant on insisting on heliocentrism. Most clerics wouldn't well understand the importance of Venus's phases, although scientists seemed to do so.

It wasn't especially easy to understand the non-anthropocentric nature of heliocentrism without a good grasp of physics. Religion and reliance upon ancient authorities bolstered anthropocentric objections, of course, but I have the feeling that people wouldn't have been especially happy to be told that their long-held phenomenological "truths" were actually not true regardless. Telling people that their "common sense" deceived them has never been made scientists very popular to the masses, and it remains a strong reason for anti-evolution prejudice.

Glen Davidson

http://tinyurl.com/mxaa3p

I think the idea was around for a long time, but like in Eco's Name of the Rose, the preservers of knowledge at the time kept eradicating the idea every time it sprung up, since it contradicted "dogmatic knowledge". We in the time of the internet are so used to new ideas popping up, getting instantly disseminated and instantly evaluated and categorized as "confirmed, plausible or busted", we can't imagine how slow knowledge spread at the time. Knowledge could literally die with a person, and how often do we find "letter written by X to Y" as first description of new finds, when the number of people of knowledge went from one to two, cutting that likelihood in half. Ethan probably has more readers than Galileo had in his lifetime.

When I read about the biggest problems in science at the moment, I do often wonder "Maybe there's something missing. Something really obvious that we're too set in our ways to notice.

Think of the hell aether-era physicists had to go through in order to explain all the strange and seemingly contradictory ways in which light behaves. All those convoluted theories and experiments they had to come up with, only to come back with more answers than questions.

It took one simple, elegant, "obvious" explanation to open up a whole new world of possibilities and technologies: there is no aether, there is no absolute reference frame.

Not to mention photons and what came later...

Makes one think about string theory, branes, multiverses, etc... maybe there is just something in our current understanding of quantum physics that we are assuming to be the only obvious explanation that simply is not true.

Knowing that this has happened so many times in the past really gets me wondering about when it will happen again that we all go "How did we not see this before! it was staring us right in the face this whole time!" and what new doors it'll open this time.

---

http://noamgr.wordpress.com

@ Tedd #11: Rutherford didn't detect electrons bouncing off of gold foil; he detected alpha particles bounding off it. An alpha particle is the nucleus of a helium atom (2 protons + 2 neutrons). You may be thinking of beta radiation.

Geocentrism has some advantages for observational astronomy. All your measurements are going to be in the reference frame of your place on earth, so if you're using a heliocentric model, you have two extra changes of coordinates. Before the telescope, there were no observational differences (phases of Venus, etc), and before Kepler no computational advantages (Copernicus' model wasn't any more accurate or simple).

It wasn't until better astronomical technology opened up observational problems that new models were needed, and Copernicus had the good timing to be suggesting one at the time.

Which is not to say Copernicus didn't have an amazing insight---he did. But it was a success largely because it filled new needs, otherwise it would probably have become just a historical footnote.

I can think of several ideas that I bet will meet their end as a result of things we already know.

1) the notion that only humans are cognitively aware and have things like cultures. That anthropomorphisation is a bad word.

2) the notion that there is a fundamental distinction between things that are alive and things that are not.

3) that "life" on Earth does not continue to originate all the time

I think you miss a point here. Rotating Earth was just an alternative way to say that stars and the Earth rotated in relation to each other, and the Church had no opposition to that - it was just mathematical modelling. Galileo's great sin was to claim that the Earth really orbited around the Sun, because that explained the phases of Venus. Psalm 104:5 explicitly states that the Earth can never ne moved. "Eppur si muove" was about annual, not daily motion.

And who was the first to conclude that the Earth is round? Not Pythagoras. The Mediterraneans were late in the game, because the Med is so narrow in N-S direction that the small change in stars could be ignored, if it was even noticed.

The Polynesians, the greatest sailors of all time, probably had it figured out by the time they had established the Lapita Culture as far south as Tonga (ca. 1000 BC). Polynesian navigators used marker stars to reach the right latitude and then sailed east or west to the island they were aiming at. They had several hundred named stars, e.g. the marker for Hawai'i was Hokule'a (Arcturus). That strategy works only if you know the Earth is round.

I suspect the first was someone who sailed the long east coast of Asia, but I have no data to present about Chinese traditions.

You should, perhaps, go and find out why the earth was consider at the centre by many Christians.

It wasn't because it was so important, rather the opposite.

The heavens pure and unsullied, the earth not so much (i.e. unpure and sullied).

Though once it was known that it was a sphere, I suspect inertia kept it central in many peoples minds; most people don't investigate what they know to be true.

@#5 Robert:

oh sure. but remember, Fleischmann and Pons are chemists too.

:)

Does anyone have a good explanation of why dark matter, dark energy, and inflationary theory aren't considered ad hoc modifications to big bang theory and therefore good indicators that (at least) one of our fundamental principles of physics is mistaken?

It is pareidolia. When you have a certain way of looking at things, you get blinded to seeing things in other ways. It is fundamentally a type 1 error, a false positive. You âseeâ the result before all the data are in and your brain can only interpret it in terms of the model that you have.

This is the major reason for the difficulty in changing scientific paradigms. The old scientists canât see things the new way because their brains force pareidolia on them.

Cody #21, because those emperors of physics at the top have such fine and nice hypotheses; if you canât see and understand those hypotheses it is because you are not fit to be a physicist and don't deserve to be funded.

@#20 rob:

But remember, Taleyarkhan is a physicist.

:-p

Ethan Siegel, my question.

Sunrise and Sunset.

Are there replacement words which are accurate?

I would like to use them if they have been invented.

thirtyfiveup,

There are, as far as I know, no replacement words. We still talk about "rising" and "setting" of the Sun, Moon, planets, and constellations. While we know now that these are just "apparent" risings and settings, we still use the same words.

Perhaps we should invent them?

Thanks for answering.

Stupid word inventions: appsing and appting

Several commenters have mentioned string theory; it and its champions have become increasingly notorious for delving deeply into theory with increasingly little data to support the possibilities they imagine. I don't pretend to have kept up with all string theory research, but reading its detractors, one gets the sense that perhaps its supporters are trying too hard to think outside the box and have come up with something that is definitely novel but barely relevant given current data. We have a similar situation in my field - the arts - as well: a glut of creators trying to be a new as possible, just for the sake of being new. Is there a handy classical word for reverse-pareidolia? That is, trying too hard to avoid current models, rather than being too thoroughly stuck inside them?

I have posted a major correction of the central claim of this post here at my own blog.

Thony,

That's a pretty good post you have written! Thanks for sharing the extra information here.

I'm so confused. So the earth us round or I could be brainwashed? It's on a string?