"Every man is free to rise as far as he's able or willing, but the degree to which he thinks determines the degree to which he'll rise." -Ayn Rand

We're all aware that one of the ways that human life on Earth could end, conceivably, is the same way that the dinosaurs went down.

And asteroid tracking and deflection technology is fast becoming one of the hot issues of the day. It appears so often in the news that you'd think we are at a high risk, any day, of being hit by a catastrophic asteroid.

But -- and my opinion here definitely runs against the mainstream -- I think this hysteria is absolutely ridiculous. One of the things you almost never hear about are the frequency and the odds of an asteroid strike harming you. If large asteroid strikes happened every few decades, we'd have something legitimate to prepare for and worry about. But if you've only got a one-in-a-million chance of an asteroid harming you over your lifetime -- meaning you are over 100 times more likely to be struck by lightning than harmed by an asteroid -- perhaps there are better ways to spend your resources.

Well, you know how we do things over here. Let's talk about the science, and find out what the odds really are!

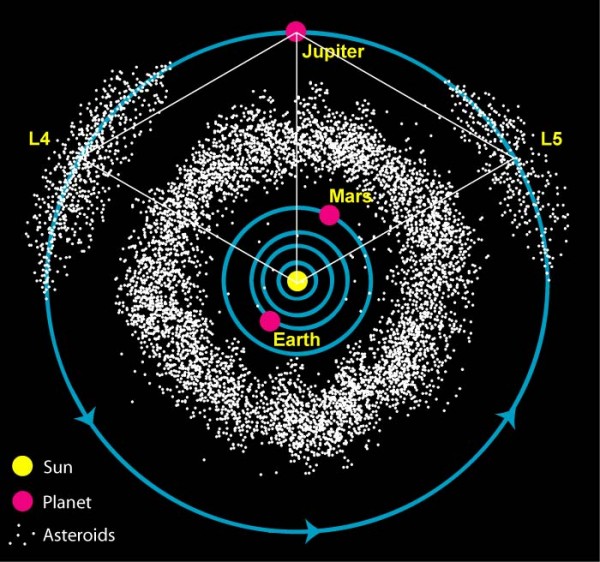

The Solar System is full of asteroids, mostly in a great belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. A few of these asteroids are very large -- 10 kilometers in size or larger -- and could make the world uninhabitable for humans should one of them collide with our planet.

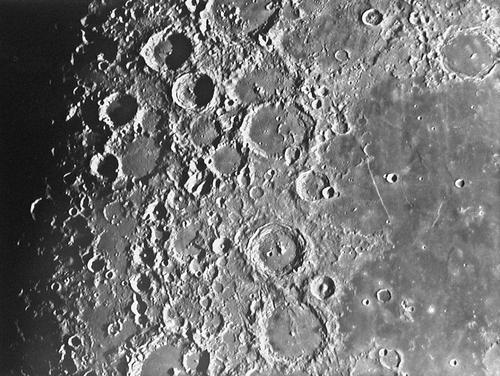

But the vast majority of asteroids that exist are much, much smaller and less harmful than these. We can learn a lot about the history of impacts in our Solar System by studying, among other things, the craters on the Moon!

Take a look at the atmosphere-less Moon's surface, above. Do you notice that there are a huge number of large craters with smaller craters atop them? This is because most of the largest asteroids that collide with a world in our Solar System do so rarely, and they did so -- mostly -- a long time ago. But smaller, less destructive impacts happen more frequently.

But who cares about the Moon when we're talking about saving the Earth? I bet you want to know what happens to our planet!

Fortunately for all of us, we have a wonderful defense shield against small asteroids: the atmosphere! An asteroid smaller than about 10 meters (33 feet) that hits the atmosphere will not make it down to the Earth's surface, nor will it affect anything that happens on the ground in any meaningful or destructive way.

All you get is a brilliant flash of light, known colloquially as a shooting star for tiny ones, or as a bolide (to astronomers, with apologies to geologists) for the larger ones!

How often do we get an asteroid larger than about 10 meters hitting the Earth? About once every thousand years. And we are "fortunate," depending on your definition of fortunate, to have had one happen only about a century ago: the Tunguska event!

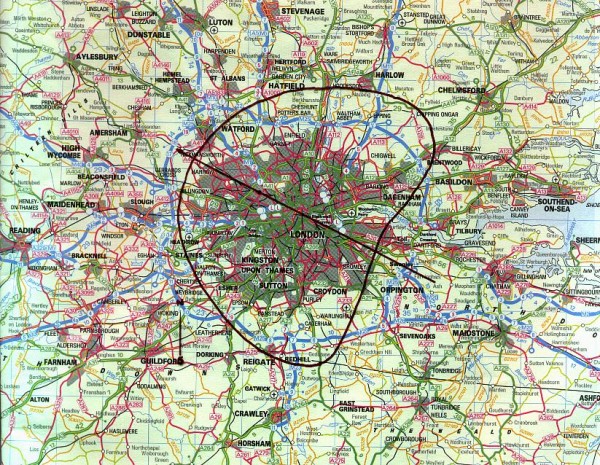

Now, this happened in a virtually uninhabited area in Russia, but the world is a much more populous place now. What would happen if something like the Tunguska event happened over a city like London?

The death toll could easily be in the millions. In addition, there are plenty of larger asteroids that -- even though they hit Earth less frequently -- cause greater amounts of damage. Once every 10,000 years, we get an asteroid that's about 40 m in diameter hitting Earth. Once every 100,000 years, we'll get an asteroid about 160 m in diameter (about one-and-a-half football fields) hitting the Earth. And about once every hundred million years, you'll get that 10 km or greater "planet-killer" asteroid headed your way.

So when we take all of these numbers, consider the entire Earth, and calculate the probability of you being killed or injured by an asteroid, what do we get, and what do we learn?

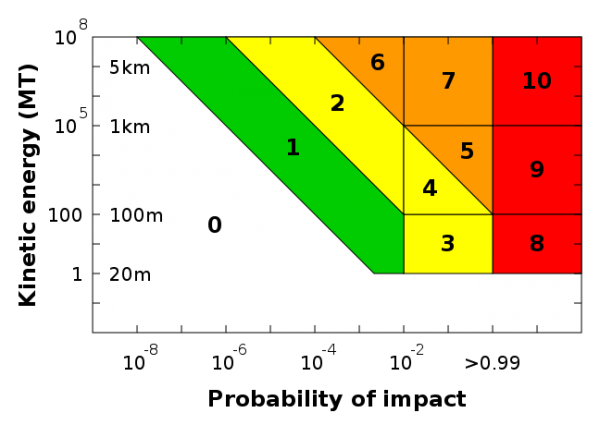

First off, we learn that the Torino Scale -- the scale that scientists have agreed upon for alerting the public about possible asteroid strikes -- only matters if we consider numbers that are eight or higher. These are the asteroids that will actually hit us.

And second off, we find that your odds of being killed or injured by an asteroid strike, in any given year, are about one-in-70,000,000. Which means, if you live to be 80, your personal odds of being harmed by an asteroid strike in your lifetime are one-in-875,000. You are more than 100 times more likely to be struck by lightning, or die in other nasty ways.

Those are your odds. Those are your scientifically, number-crunched odds of being killed or injured by an asteroid here on Earth. If you're terrified of those odds, so be it. But don't let anyone exaggerate these odds to you, don't let something with a Torino scale rating of 1 or 2 or 3 cause you to lose sleep at night, and please, if you're a policymaker, consider this reality when you make your policy.

Thank you, and if you're in the United States today, don't forget to vote!

This is the same as the difference between the number of people killed each year in traffic vs the number of people dying in airplane crashes.

It is a bit like the following:

At this point for the average human the brain shuts down due to the inability to process large numbers and goes :"oh no millions of people dead at the same time I better panic" rendering the rest of the explanation moot.

"How often do we get an asteroid larger than about 10 meters hitting the Earth? About once every thousand years." This is off by several orders of magnitude: According to the impact frequency diagram used in the NEO community (this one I obtained in 2008; are there newer ones?) 10 meter bodies hit the atmosphere at least once per decade. One thousand years is more like the rough average interval between Tunguska-like impacts which are already well into the locally destructive size range.

That is roughly my position as well, the actual ROI will be imperceptible.

If a crust buster would risk sterilizing the biosphere it would have happened by now. 4.5 Gy on a non-stationary Poisson process (non-stationary since the risk goes down as the impactor population drain of thanks to Jupiter et al) without any hit means it's a low rate - and there's only 2 Gy to go, tops. So that part is pure scaremongering, not facts.

The main reason to work on this is that it would be the only 2nd time humanity comes together to avoid an environmental disaster after the ozone hole PFC stop. It would influence future efforts positively, I believe, showing that we can do this consistently. (Though avoiding serious AGW effects is too late now - too bad since _that_ would have been both easy and _major_ ROI.)

I think the reason there is buzz about this unlikely threat from space rather than, say, earth being fried by a milky way gamma ray burst is that we have the technology to do something about it and, more importantly, the operators of that technology (NASA, DOE, DOD) are a constituency fighting for budget dollars.

I guess you're right if you're only concerned over one's own life then the concern is overblown, but if one is concerned over the long term survival of the species, let alone civilization, then maybe the threat of a cosmic impact which the geological record is just now revealing to more frequent than the old school geological thinking suggested. At one time not too long ago impact craters were considered to be one of the rarest of geological features and these days we're finding a whole lot more than was previously imagined. Back when our population was primarily composed of small relatively isolated bands of pre-civilized pre-technological humans, a blast that might wipe out a percentage of us wasn't a big deal. If half the population of humans or more were dead as a result it really didn't change the over-all game much. I think it's a pretty big deal these days as a big impact, even if it didn't kill us off directly would disrupt agriculture and distribution, and a whole lot more resulting in misery beyond immediate death.

We do live in an age when our technology might actually do something practical regarding this particular threat of game-changing impact events, not to say that it would guarantee our protection since there maybe other more formidable cosmic threats we can barely imagine. It is irresponsible to not work towards some degree of protection, and while in the process become a space faring civilization as we will have to one day anyhow unless we want all our eggs to just sit here in our single basket, and never before ( and who knows when we will again) have we had at our disposal the energy and knowledge that we do now.

Daniel @2,

That graph you point to is great, and has newer data than I was familiar with! As far as I understand it -- and I may need to be corrected here -- the energy vs. frequency is the fairly certain thing that's measured on that graph.

But I had thought that the size was very uncertain. For the Tunguska event, I have heard various estimates as to its size: ranging from 10 km (the value I used) to 40 km (the value your graph uses). All of my calculations proceeded from there, and are identical if you go off of the energy, but may require adjustments to the size if, indeed, the sizes of these impactors are better determined.

Doug l @5,

What you're espousing is exactly why I've written this article. There are much, much, much better uses of our resources to protect and ensure the long-term survival of humanity than building asteroid deflectors. It is very, very likely that we will have no major asteroid impacts on Earth over the next 1,000 years, let alone the next 100. It is very likely that there will be no species-threatening impacts over the next 10 million years, let alone the next 100.

While I applaud the long-sightedness and the technological development that goes into projects like asteroid deflection, one must be realistic about the odds of "losing the lottery" and whether it's worth the devotion of resources you advocate.

If I stand with one foot in a bucket of ice and one foot in a bucket of boiling water, on average, I'm comfortable. You cite the statistic that the chance of being struck in any one year is 1 in 70 million. So, statistically, because there are 300 million people living in the U.S., we should expect 4 to 5 people to be struck each year. On average, 57 people are killed in the U.S. by lightning each year. If our chances of being struck by an asteroid are only 100 times less than that, we should see one person struck every other year. I have watched two one-hundred-year-storms strike within a period of six days of each other. And, of course, the day before the Tunguska event the odds against it happening were (pardon the pun) astronomical. My assessment of the odds goes something like this: Didn't happen today; might not happen tomorrow. .

Ethan, while you calculate for direct results from being impacted by an asteroid, you do not take into account the fact that while a large one may strike someone and somewhere else, it may yet affect the planet in certain ways (temperature, etc.) that could have a detrimental impact on us all, even if one were half way across the globe from an impact site.

I would be interested in knowing how great a diversion of resources is really being suggested.

My take on the whole thing has been that the odds are incredibly low (as you rightly point out) but that the consequences is so high, and the resources required are so low, that it is worth putting some effort into just in case.

I advocate this with the knowledge that my chances of being personally effected are incredibly low.

I happen to care about what my grand^200 childrens lives are like though (as well as their contemporaries). If you don't I can't argue with you but I do in the same sense and for the same reason as I care what my grandchildrens lives are like (again, as well as the people they share the planet with).

Now of course my argument is void if there needs to be a large amount of resources diverted. The consequences of an asteroid impact would not, in my opinion, justify a fully fledged test of the gravity tug method (for example). There are too many worthy projects who need a ride to space for me to justify that to myself.

It's not at all clear to me where that 1/70,000,000 chance of being killed by an asteroid came from. Could you clarify that?

If you take that number, it bulk of the probability comes from the 10^-8 chance of being around for a planet-killer, which is not what I would have expected. I'd expect the far more frequent asteroids causing regional devastation would be far more likely to kill you (especially indirectly through climactic effects and ensuing economic disruption/collapse).

Nothing but questions here. How well are we able to detect the asteroids that can cause significant damage, and at what range? Could a 40m body wreck downtown Portland? Or would it take a 100m rock? And how long would we see it coming? It seems to me that I don't know enough to be worried.

So... about 85 people die each year from rocks falling from space? I had no idea it was so many.

Certainly the risk to me is very very low.

However, your feel of probability is a little off. "How often do we get an asteroid larger than about 10 meters hitting the Earth? About once every thousand years. And we are 'fortunate,' depending on your definition of fortunate, to have had one happen only about a century ago: the Tunguska event!" The asteroids are not queuing up in space nor loitering around having taken a number from a dispenser. The Tunguska event doesn't buy us 900 years of immunity from a similar event. If flipping a coin, I get 10 heads in a row, it doesn't mean that I'll probably get a tails on the 11th flip.

The risk of asteroids smashing into the earth is extremely low. Panic is absolutely not called for. But I do think that it is worthwhile studying these objects as they tell us a lot about our own planet and solar system.

I'm not worried about dying from a bolt of lightning. But at the same time, I don't want to be ignorant about the phenomenon, lest I find myself wandering out onto a golf course to admire a thunderstorm. By the same token, we should study asteroids and consider ways to move them, just in the remote chance that one wanders in our path.

I heard a speech given by Dr. David Morrison (NASA Lunar Science Institute & SETI Institute)in which he said that even if we did have reasonable means of detection, any asteroid that comes from behind our line of sight from the sun and we have effectively a zero chance of detecting it. If a huge one does come barreling in, I would rather have it land on my head then deal with the difficulties that would follow a game-ending impact.

Asteroids are not a problem for me. I use Preparation A.

Having said that, great blogging and comments! Thanks!

Asteroid Deflection as a Public Good

Link: http://www.marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2009/12/asteroid-d…

There is a 1-in-10,000 chance that a large (approx2-km diameter) asteroid or comet will collide with the Earth during the next century, disrupting the ecosphere and killing a large fraction of the world's population. Although impacts of this magnitude are so infrequent as to be beyond our personal experience, the long-term statistical hazard is comparable to that of many other, more familiar natural disasters, raising the question of whether mitigation measures should be considered.

What year in the near future should there be a high chance of an asteroid coming through the Earths atmosphere?

This is like anything else.If it's instantaneous you won't know what hit you!Me worry?>Not!

Although the probability is so tiny (and I certainly wouldn't say one should "worry" about it), the risk is great. However, as you note in your reply to another comment, resources are limited, and there may be better ways to mitigate this (and other) existential threats. For one, I would be absolutely thrilled to see a self-sufficient off-world colony in my lifetime, and in the significantly nearer term I hope to see more certain threats mitigated, such as through a drastic decrease in fossil fuel consumption.

Or a technological singularity, but that goes without saying.

A thought about the moon craters:

Doesn't underlying small craters get erased by later larger craters? So the statistics of small=new, large=old moon craters says very little?

And one about where our killer would come from:

And how is the distribution of risk - is it the ones between Mars and Jupiter, is it the Jupiter Trojans, or is it another meteor that will kill us?

But, most commentors seem to be saying we should spend resources on protection from these things. But isn't the question whether we should spend on something we know will happen soon - climate change, or spend on this negative lottery ticket?

Regardless of the probabilities, the power to deflect meteors would be a dangerous game changer because deflect is just another way of saying steer or aim. Sword of Damocles indeed. And, it has an element of stealth and deniability. On the other hand, practicing guiding meteorite impact to a designated destination could revolutionize planetary science. An impact large enough to excite free oscillations of a planet or moon (or Moon) would provide us with an enormous trove of valuable information about that body's interior, were we to land a long period seismometer. It would also help us calibrate the actual damage done, something we need if we are to discuss this issue in a meaningful manner. For example, there are still those who claim that impacts into the ocean would cause world wide tsunamis, despite a marked lack of evidence of global and contemporaneous turbidite and clastic deposits that would result from such a "killer" wave.

Summary: The control of meteors and where/when they land is strategically dangerous but even richer in its scientific fallout (who can resist the irresistible pun?)Certainly not me.

I totally agree with MutantJedi.

I'll add, much of the money spent on this is in the NEO detection systems, right? (What, LINEAR & And those have additional value, mapping of the solar system, further verifying our models of gravity & solar system dynamics. There may even be other important benefits to that knowledge. But they aren't super expensive, are they? Are we spending many billions of dollars on impact detection/prevention?

Whoa, and wait a minute... the Torino scale cut off for energy is 1 megaton? So any event less than 1 MT is too small to warrant public attention? regardless of probability?

It's not something to fear, but like all things, it is certainly something to understand more completely.

@Ethan #6: My diagram (which had first appeared in a Nature article in 2008 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Tunguska; the author mailed me this more detailled version) has one y axis (frequency of event) but several x axes; the green one on the bottom is the diameter of the impactor in km. For Tunguska the size estimate of the stony asteroid involved is usually given as about 50 meters (not kilometers; now that would have been a bang ...), though one recent simulation 'made' the airburst with just a 20-meter body.

"Every man is free to rise as far as he's able or willing, but the degree to which he thinks determines the degree to which he'll rise." -Ayn Rand

Rand never met The Situation.

Each persons odds of dying are 1-in-1; and our species homo sapiens odds of going extinct are 1-in-1; but detailed breakdown of these odds seldom informs policymakers' decisions or individual's decisions. For Example:

Heart attacks are #1 cause of death in U.S..

Cholesterol clots in arteries are #1 cause of heart attacks.

Cheeseburger is #1 fast food in the U.S. and has no warning label.

Thus an asteroid defense shield has the food industries' support.

Hi! I got it now! #4 said killer Milky Way gamma ray bursts! What we have to do is to make a Disaster FIlm from that: Let's work out the physics, and if they're not perfect we'll tweak them a bit. A scientist figures out that there'll be a killer gamma ray burst, and it will last say 6 hours - so it will fry 3/4 of the planet as it during that time exposes that much while turning. Mad scientist gets to know too late, so he can only try and get to the safe zone - but the infrastructure is breaking down so he has to move fast as the world turns and his current location will be fried in hours/minutes/seconds.

Can we keep it between us and share the revenue?

The only real "overreaction" that is apparent to me is TV shows, especially science shows, that make a big issue out of this. In the real world, we are spending maybe a few million per year monitoring near earth object, and I think that can be justified on science grounds alone.

I didn't like your sentence about objects under 10M not hitting the ground in any meaningful way. I assume you meant with any decent fraction of the original kinetic energy. We still get meteors, which are usually just pieces of smallish objects that broke up in the atmosphere. And there is a nonzero probability of being hit by say a 200gram rock from space -which could easily kill you, even if it is only going a few tens of meters per second.

The gammy burst movie is a nice idea, only the plot is so short. Burst lasts 1 min. Atmosphere is blown of planet. The end.

The special effects possibilities of course are impressive.

The probability of individual death is 1.0, but most humans prefer to live to their natural lifespans, despite "lifestyle" risks. The probability of humans going extinct asymptotically approaches 1.0, but it makes a difference whether extinction occurs through evolution into a different species, or through a preventable failure such as overpopulation/ overconsumption/ war with WMDs/ etc.

Failure to become a spacefaring species is an example of a preventable failure since it leaves us with all of our proverbial eggs in one planetary basket in one solar system, eventually to be incinerated when the Sun goes red giant a few billion years from now. This is "cosmic selection" at work: natural selection on the cosmic scale, as some intelligent civilizations will succeed and proliferate across the galaxy while others will not.

As an ethical proposition we do not have the right to deny our distant descendants the right to choose whether or not to live and spread across the galaxy. Yet we could fail there as well, by squandering natural resources that are essential toward making the transition to Mars and then the stars: by analogy, climbing down a hole and then burning the ladder for amusement, and being unable to climb out.

So here's where this ties back into the issue of object impacts on Earth.

The processes by which we become a spacefaring civilization will have among their side-effects the development and deployment of technologies that will aid in detecting and dealing with large objects in space. (By analogy the development of heavy industry has as a side-effect the ability to manufacture military hardware should it ever be needed.) The incremental cost of adding the final pieces will be relatively low. (By analogy if we're already building an assembly line, let's allocate a small part of its time to producing some tanks.) And in all probability we could have those pieces in place before our next encounter with a truly dangerous object.

So those are our choices: do the right thing for science, for our descendants, and for passing the cosmic Darwin test, or squander our resources on circuses and baubles until we lack the means to get off this rock altogether.

The question for our policy makers shouldn't be whether to allocate large budget to object detection and diversion in a proverbial vacuum, but whether to continue the forward movement into space, of which object avoidance is just one very small part of the big picture.

What are the chances of an asteroid wiping out all trace of Ayn Rand's existence from the planet?

#27 - damn, knew science would mess with my script. Rework science or rework script?

#28 - if we need to leave the planet before the sun goes out, and we currently have limited resources, should we then prioritize leaving the planet or instead focus on current upcoming disasters? Or did you mean we will waste all our natural resources on saving ourselves momentarily from WMDs and global warming and ozone layers an whatnot so when the time comes in a few billion years, we won't have gas and cache enough to start up the big space ship?

Joffemannen @ #30:

The choice isn't between a) going interplanetary and then interstellar vs. b) detecting and getting rid of objects that might hit the Earth.

Developing the technology to do (a) necessarily results in having the means to do (b), per my analogy about assembly lines and making a few tanks.

The choice is between (a)+(b) VS. baubles & circuses that burn through resources for no good reason. Amusement is not a good reason: it's a few micrograms of neuropeptides excreted under the direction of chimp instincts to grasp at anything shiny and new.

The choice is between serving those chimp instincts at the expense of all of our concentrated energy supplies (keyword search "the 28th day" and understand the principle of exponential growth), VS. serving the long term interests of the evolution of the species.

As a deontological matter, we do not have the right to deny choices to our distant descendants, particularly for the most trivial of reasons. As a consequentialist matter, the amount of suffering we would thereby inflict upon our distant descendants is of enormous magnitude greater than that which would be suffered by foregoing some baubles today.

One doesn't even need to invoke theology here, only the principle that all living organisms seek to preserve their own lives (with few exceptions that underline the rule), as the first observable behavior of every organism down to single cells attempting to maintain cellular homeostasis.

Here are our concentrated energy sources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, uranium, and thorium, perhaps a couple more I'm forgetting at the moment (I'm sick & have a fever so my brain is running at about half capacity which kinda stinks). I'm not including H2 for fusion because that has not been demonstrated feasible and one of my ground rules is "no miracles." I'm all in favor of research on fusion, and if we can do it, then it's a windfall. But I'm not in favor of taking it for granted, because that is intellectual laziness that ducks the question.

Now look up exponential growth and the concept of "doubling times." That is the danger we face of depleting resources such that the best we can hope for is a life in the caves waiting for the Sun to turn into a red giant and roast us.

Between here and the Sun going red giant, there's more than enough time for Earth to be threatened by various space rocks. But dealing with that issue becomes easy once we're in space in a serious way. What I'm saying here is that this will take care of itself if we do what we need to do in order to pass the test of natural selection on a cosmic scale. But it won't if we don't.

Ask yourself this: What do I have right now, that I would be willing to give up, in order for my descendants both close in time and far-away in time, to have the choice of whether to live or die? And then ask yourself what else becomes true as a result of various answers to that question.

But if I have to believe to Phil Plait we´re all going to die.

choices choices

I don´t know yet.

We´ll see.

What would I give up? Hmm... If I park my Prius and commute by train instead? But then I'll be all too tired when I get home in the afternoon to create those descendants.

g724

Nicely expressed ideas, but too sentimental. "we do not have the right to deny choices to our distant descendants"

Obviously, our immediate and distant ancestors denied us many chooses. As well, we shall deny our descendants many choices. But evolution isn't about individual or species choices for survival; it is about species emergence.

Some of the unintended consequences of human population growth and survival upon planet Earth are cockroahes, rats, bedbugs, invasive species, habitat destruction, and massive species extinction (i.e. dimisnished biodiversity).

But such imbalance (i.e. species extinction) increases risk of extinction for surviving species (e.g. humans, cockroaches) due to disease, pestilence, famine.

Which means opportunity for emergence of new species (e.g. massive extinction during age of dinosaurs opened opportunity for mammal evolution).

So if as a species, human's goal is survival; then managing a balance within planet Earth's ecosystems is essential. If on the other hand, human's goal is massive evolution; then destroying Earth's ecosystem and massive extinction might help.

Now about this little matter of deflecting asteroids. It is unlikely that even a very large asteroid, such as wiped out the dinosaurs, would wipe out every survivalist with caches of food, tools and weapons hidden in the mountains from Afghanistan to Montana.

Thus survival of the humans species might be lengthened if our largest cities got hit with many major asteroids. I mean, 10,000 years ago the human population was 5,000,000 and today it is 6,000,000,000.

Thus the reduction of human population to 5,000,000 (keeping our technology intact, of course) might give humans another 10,000 years of survival to achieve your sentimental goal of sexually active humans throughout the Milky way galaxy and beyond.

Abraham would be proud of your post haste goal of populating the Galaxy with homo sapiens. But he would opt for sacrificing a dozen of his sons (and their multiple wifes) in spacecraft to the nearest dozen star systems; rather than wasting precious resources trying to protect against near hit asteroids which nearly always miss.

What's being left out in this discussion is evacuation. The larger the asteroid, the more time to evacuate. If we were to detect an incoming Tunguska at 3 days out (typical), people living at ground zero would learn via media and would, over several days, be able to slowly walk (0.3mph) to safety. So the risk of death is much smaller than stated in the above discussion.

Of course, there could be some common responses. But an asteroid coming from the sun direction would be only a small fraction of potential directions and wouldn't radar be able to detect it? Also, a climate-changing impactor also wouldn't likely kill many people for the following reasons:

- they are so rare,

- we are getting close to knowing where 100% of the really big ones are.

- they would be detected years to centuries in advance giving time for a specific (small) deflection intervention

- Large illuminated greenhouses could keep agriculture going.

It is true that not much money is being spent on deflection programs. But there is talk and it is not unthinkable that congress could mandate NASA to build something wasteful.

I would much rather money be spent on #1 a long-term, hermetically sealed bunker and a self-sustaining lunar colony be built as insurance against our own self-replicating technology which, IMO, is a far far higher risk than extinction by asteroid.

Is asteroid detection and mitigation worth the cost despite the risk of asteroid impact being a "negative lottery ticket?" Yes. For at least three reasons.

First, the impact (no pun intended) of a natural disaster is not measured solely by its frequency. Unlikely events with catastrophic results can be equally worthy of preparation as are frequent events with minimal results. A magnitude 7+ earthquake out of the New Madrid or Upper Wabash Seismic Zones is unlikely. A category 4+ hurricane probably won't hit New York City. But we prepare for these events (and probably should do so more vigorously). That's the principle of disaster management. A large asteroid impact is the ultimate risk. Let's ignore crust bursters -- even an impact capable of regional decimation might mean a billion dead from a strike on the US east coast, Western Europe, or India, not counting deaths from secondary causes due to infrastructure debilitation. Perhaps an impact of that size could happen every 10 million years. That's potentially 1000 deaths a year over the aggregate. Add in the impactors of other sizes (mostly more common objects with fewer deaths), and from the disaster management perspective, asteroids look more like the risk to life posed by hurricanes in North Carolina, rather than New York City.

Second, asteroid mitigation is important because not everywhere we will someday want to live is Earth. The moon, Mars -- indeed, most solid bodies in the Solar System -- do not have our wonderful atmosphere. Within the last decade, we've seen (at least) three objects impact Jupiter, one intra-asteroid-belt collision, and evidence of several strikes on Mars. Every body that we inhabit increases the chances that the disaster occurs. Not every body that we will someday inhabit has the same protections that we do, or the same risks (there are many more Mars-crossing rocks than Earth-crossers).

But finally, let's set aside the impact prevention aspect of asteroid detection and mitigation entirely. This discussion mentions ROI. The ROI here is not solely the value of preventing an actual disaster. There is pure and applied science involved. We are locating NEOs. We are beginning to send probes to them. The idea of a manned mission to a NEO has some currency as a stepping stone to Mars. Gaining the ability to locate, travel to, and manipulate these objects allows us to use them as resources. Perhaps we'll build a system of communications towers on NEOs to serve as information relays as we expand outward. Perhaps we'll partake in asteroid mining. Perhaps in the distant future, mankind will make an attempt at Martian or Venerean terraforming, beginning with ice-enriched impacts. But beyond anything we can imagine now, the rewards of science and engineering are almost always in the things we do not now know and cannot imagine.

The threat of a rock from space killing us all is remote. Asteroid monitoring and mitigation is not cause to panic. Neither should the residents of St. Louis panic over the New Madrid, the citizens of Chicago over the Upper Wabash, or the city of New York about a repeat of the 1938 Long Island Express (or the more powerful storm around ~1300). But the choice is never simply between panic and inaction.

Given the probability of getting struck by an asteroid, and the immense cost involved in creating anti-asteroid defenses, I completely agree with this assessment. The risks associated with asteroid impacts are insignificant, especially when compared to much more likely events such as catastrophic events associated with climate change, or technological advancements in the form of military defenses (nuclear bombs, biological warfare, and the like). Therefore, you should be much more worried about these possibilities, and invest in preventative measures for them. It would be a much more beneficial investment.

A hungry person, or a person who is homeless or can't afford health care, can at least feel a bit more secure knowing that their government is investing in asteroid monitoring & deflection technologies, for the sake of protecting public well being, of course.

Joffemannen #33:

If you're driving a Prius chances are you're also doing other things to reduce your impacts as well, so you're already ahead of the vast majority. We need to get more people doing those things. Best part is, those are contagious. "NIce car, John." "Yeah, my fuel costs dropped by half." "Really? Hmm, when it's time to replace my wheels I'll look into that." Same thing for rooftop solar: one person in a neighborhood gets it, and the neighbors get interested, and then they start going solar too.

For folks who can't afford a new hybrid, if your car was made in '96 or later, you can use something called ScanGauge (keyword search it, cost is @ $168) to get realtime MPG feedback, and thereby learn driving habits that reduce fuel consumption. My vehicle is rated 22/25, but using ScanGauge I'm typically getting 25/30 and sometimes better than 30 highway. (Though most days I telecommute.) (And the thing that really kills mileage is stop-and-go, which is one place hybrids have a huge advantage.)

BTW, when I put fossil fuels on my list of concentrated energy sources I did not intend the idea that we could just start burning coal as oil got more expensive. Bottom line is, we have to go climate clean or we'll never get far enough to see humans on Mars much less another Tunguska. This means nuclear and renewables.

AngelGabriel #34:

Hardly more sentimental than the traffic cop saying "you can't park there, that's a red zone for fire engines." (Surprisingly, there are people who actually argue "but there's no fire right now!") It matter-of-factly follows from the usual starting points of deontology such as the categorical imperative. I have little patience for sentimentalism ("oh the humanity!" sob sob!), and I can derive deontological ethics from a few basic observables of biology: the instinct for self-preservation, approach/avoidance behavior, etc. (Anyone who wants to argue that I'm committing an is/ought error there, let's take up that subject separately.)

The fact that someone else did it (our distant ancestors denying us choices) doesn't make it right for us to do it; otherwise there would be no basis for the ethical evolution of cultures. And in any case, here we are talking about the issue of the survival vs. extinction of the entire genetic and memetic lineage that have developed on Earth: no previous generation in history has had the ability to make choices that determine whether or not Earth life & memes will or will not continue.

As an ethical matter there is a difference between truly unintended consequences, and consequences that are foreseeable. The worldview born of science & rationalism necessarily entails an increasing degree of ethical responsibility: the more we know about the physical universe including ourselves, the greater the range of facts we are obligated to consider when making decisions.

Re. "if the goal is massive evolution, then destroying Earth's ecosystems and massive extinction might help." There are two problems with this: One is the error called "picking and choosing disasters." The other is the issue of imperfect knowledge.

First, very often people envision various disasters occurring in a manner that leaves an opening for some desired outcome IF they themselves (or others, or humanity at-large) takes some prescribed action. The problem is that disasters don't work that way: they don't accord with our expectations, and there are many unforeseen aspects that end up making things worse even for those who prepare.

Second, if we set off down that road of massive ecosystem disruption expecting a desired outcome, we will run into a very large number of unforeseen outcomes, and we don't know ahead of time if we'll overshoot or undershoot the target. The probability is much higher of missing than hitting the target outcome, and the risk/benefit relationship makes it untenable.

I don't know what Abraham would do, but given the present state of physics, we can expect an interstellar journey to require a many-generational colony ship and a voyage of thousands of years, even at a respectable single-digit percentage of c. And per my "don't count on miracles" principle, we need to make our plans today based on today's physics. If breakthroughs give us the means for faster journeys, that's nice but shouldn't be counted on.

Re. John Hunt #35:

The error there is that we do not have sufficiently accurate means to measure all of the values of relevant variables for any given object, to predict where it will come down, nor are we likely to have such means in the foreseeable future. The best we'll be able to do is a rough estimate, and depending on where it is, the number of people to be moved may be so large that the logistical problems are intractable.

Large illuminated greenhouses will only be able to provide for the needs of a small fraction of humanity. Consider the time needed to build them, and the time needed to get them into production. Also beware here of the error of picking & choosing disasters: reality will be quite a bit messier.

More later, I gotta scoot for now...

my opinion here definitely runs against the mainstream -- I think this hysteria is absolutely ridiculous

Actually, I think that is mainstream opinion, and that is why hysteria is not happening at any significant level.

Undertaking thoughtful investigation != hysteria.

This article is an extraordinary piece of work. I really like how you got right to the heart of how asteroid strikes truly affect our Earth. I actually never knew that an asteroid had to be over 10 meters long to even touch the Earthâs surface. Also, I agree with your theory that the people on Earth right now shouldnât have to worry about a meteoroid strike. I have always been in disagreement about all of these conspiracy theories, and next to 2012, this is the most common one I hear about on TV. Itâs nice to hear that the odds are very, very slim that the people of Earth have a âdinosaur â likeâ experience. But itâs also disturbing to hear how much money has been going into meteor tracking. My biggest question is, if the chances are so slim, why are scientists following these asteroids so religiously, just so they can find the next âplanet â killer,â when the reality is that itâs probably still in the Asteroid Belt?

The article holds no value. The only statistic that really matters is that the chances of an asteroid hitting the planet creating a planet wide extinction and likely end to human civilization, before we're ready to be eliminated is 100%. Sometime, and nobody can remotely predict when, a huge asteroid will hit the planet that will eliminate, burn, kill, detroy, most of the mega-life forms on earth, and the last one wasn't that long ago in geological time. No matter how small the odds of that happening in your lifetime, the consequences are serious enough to mandate a plan to track asteroids, and be prepared to deflect them, when that time is necessary...and that time WILL come.

BTW - the odds on the day that the Dinosaurs were destroyed by an asteroid of being struck be a an asteroid, was exactly the same as today. That is the great beauty of statistics.

I found it ironic that so many people get worked up about asteroids when the chances of being injured by one are so little. If people are informed on the actual statistics of asteroid hits, this could prevent a great amount of worry and fear. I am glad to find out that only an eight or higher on the Torino scale should spark concern for people, and that most asteroids wind up never making it to earth. That gives me more reassurance about the topic and causes me to be hardly concerned about asteroids hitting the earth. I canât believe that you are 100 times more likely to be struck by lightning then by an asteroid! I knew asteroid hits were uncommon, but not this uncommon. You mentioned that a 40 m asteroid hits the earth every 10,000 years and that a 160 m asteroid hits the earth every 100,000 years. Do you recall when the last time these hit the earth were? When is an asteroid 40 m or larger projected to hit the earth, and what measures can we take if it is close?

Sure, the odds are in our favor. That won't mean a thing when (not "if")the Gravitational Pinball Machine tosses a ball toward our gate. The problem is that the downside is very, very bad.

Considering would have happened if the Tunguska event had occurred over London is an excellent thought experiment. But consider what would have happened if the Tunguska event had occurred over Tunguska around 1985 or so. A lot of ICBMs might have been in the air before someone realized the blast wasn't nuclear.

Oops! That ruined the whole day....

For me, another thing to consider is the possible payoff. If we develop the capability to push a Dinosaur Killer out of the way, we'll also have developed capabilities we can use right away. Just off the top of my head, consider having the capability to move a nice, metal-rich rock to a convenient location and mine it.

We have to get back to thinking beyond income for the next fiscal period.

Let's see. Some people say buying a lottery ticket is foolish because your odds of winning are like ZERO. Yet, sooner or later someone wins.

Ditto an asteroid. The chances may be one in a billion of getting hit by a big one, but yet it's possible. And then you have to factor in the what if. Like "what if" the statistics are correct, but we have an non-statistical event? You do know that famous saying don't you? Sh*t Happens!!

Sure, maybe our odds are low of getting hit by one today, but that doesn't mean we can't steer one our way. Why wait for the inevitable, when we can make it happen! YES, Embrace asteroids, don't shun them!! If we can get them to orbit the earth nicely, they'll make cool places to land spaceships on, and hop off for scenic tours. Look at our moon - it's mostly round and dull - and just look at those asteroids - wow, all sorts of cool shapes and sizes, and some could contain iridium just the one that wiped out the Dino's. Why let Jupiter have all the moons? Let's send some rockets up there, push some asteroids our way, and start giving the night sky watchers some pretty new moons to gaze at!

Just bumped into your blog today. Very nice, thanks.

I did notice this:-

1. - sorry I noticed a couple more and added numbers.

"the Earth also radiates the energy absorbed during the day back into space at night."

While true I don't think it is complete. The Earth will surely radiate back into space during the day too? I doubt that the incoming solar radiation beats back the outgoing stuff:-)

2.

You don't mention radiation simply reflected from the Earth's surface. I can see that you didn't want to add even more complexity but maybe a mention?

3.

"What happens to that energy after the CO2 absorbs it?

It gets re-radiated back towards Earth"

Well some of it will, but surely some will be re-radiated towards space. Maybe close to 50/50 at a guess but I am no physicist.

Very clear and succinct explanation I feel guilty about the nitpicking but think that [1] is worth fixing.

âTechnically, theyâre correct, there is a chance in 2036 [that Apophis will hit Earth]," said Donald Yeomans, head of NASAâs Near-Earth Object Program Office. However, that chance is just 1-in-250,000, Yeomans said.

http://www.csmonitor.com/Science/2011/0207/Apophis-asteroid-will-probab…

Whereas there is 1 chance in 450,000 that a plane will crash on a given flight.

So Ethan, how about a refresh: Is a 200 meter asteroid with a 1-in-250,000 chance of hitting the Earth (according to NASA's Yeomans) a big deal or not.

This page made me feel a WHOLE lot better. I was looking around on the internet for info on this (I admit, I had a bad nightmare about an asteroid hitting the earth and it freaked me out). I have to say, this page does put me a little more at ease, THANK YOU!

People have odd ideas about probablilities..... A 1 in a Million chance of being hit by an asteroid does NOT means it will only happen once every million years. It could happen tommorrow and on the following day. Probability is just a measure of the average over a large group of occurrances.

Second, the 'odds' for Apophis are based on the error and uncertainties in the calculated orbit rather than a game of chance.

really good you wrote lots of facts there i sat withought telliung my kids and read every single paragraph out of that

that sucked all a lie