"If it were worth the while to settle in those parts near to the Pleiades or the Hyades, to Aldebaran or Altair, then I was really there, or at an equal remoteness from the life which I had left behind, dwindled and twinkling with as fine a ray to my nearest neighbor, and to be seen only in moonless nights by him." -Henry David Thoreau

Two weeks ago, I asked if you knew your brightest stars. And there are some spectacular ones, of course.

But our nearest major star, alpha centauri, the yellow guy (below, found near the Southern Cross) is over four light years away from us.

But not every star is as lonely as ours is! Stars, as you may know, don't form one-at-a-time, in isolation. They form in large groups, or clusters, all throughout the spiral arms of galaxies. In fact, looking at a distant galaxy, everywhere you see these "pink" regions, those are regions where the galaxy is forming stars!

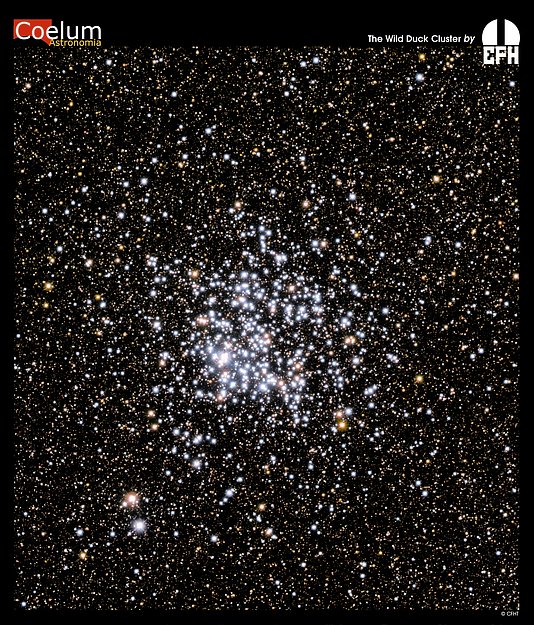

Well, obviously we can't see that well in our own galaxy, but we do have regions just like that! We call them open star clusters, like Messier 11, below.

Some open star clusters are farther away, like this beautiful one in the Small Magellanic Cloud, NGC 265, as imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope.

But perhaps the most famous open star cluster is the Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters, or simply Messier 45.

Of course, none of these are actually the closest to us; the Pleiades is simply the brightest star cluster in the night sky.

But if you can learn how to find the Pleiades, you can find our closest star cluster! Here's how it goes.

For a few more days, you'll be able to see Orion in the night sky. Follow the belt across to the bright cluster of blue stars; that bright blue cluster (if you have good vision, you may even be able to make out seven separate stars) is the Pleiades.

But now, I'm going to ask you to look between Orion and the Pleiades.

There's a bright, giant orange star there: Aldebaran, which just missed my list of brightest notable stars, coming in at the 13th brightest in the Sky. You'll also notice four other dimmer, but still pretty-bright stars, that help form a big "V" in the sky. They're part of the constellation Taurus the Bull, and we can take a close look at that region thanks to Lynn Laux's photo, below.

Those four other stars are located about 151 light years away, and are some of the brighter stars in our closest star cluster, the Hyades!

If this is the closest one to us, you ask, why is it so dim compared to the Pleiades? After all, there are hundreds of stars located in a pretty dense cluster!

The answer is its age. Most star clusters only live a few hundred million years, but the Hyades is almost ancient, at 625 million years old!

How do we know?

Image credit: Atlas of the Universe, which is appropriate, since the Hyades are the five daughters of Atlas!

Stars form on this curved line: the bluer ones are the hotter, brighter, more massive ones. But they also burn through their fuel the most quickly! When a star cluster is first formed, it makes all the different types of stars, from the bright, blue, ultra-massive O-stars to the dim, red, barely-burning-their-fuel M-stars. But after just a few million years, the O-stars are all gone. (Even the Pleiades is out of O-stars!)

The Hyades is out of B-stars, but contains many more A-stars and F-stars than our neighborhood does; it even contains 8 white dwarf stars, which are the corpses of B-stars that weren't quite massive enough to make it to a supernova!

At 625 million years, it's an oldie but a goodie. And at just 151 light-years away, it might be an ideal place to find a young world to colonize someday! But you'd better move fast, because these stars won't stay bound together for long. Why not? Break out your red/green 3-D glasses if you've got them, because you'll want to see this animation.

The Hyades are flying apart! Open star clusters don't live very long because, when you get a large number of massive objects together like that, gravitational interactions periodically kick stars out, eventually dissipating the cluster and just leaving a large number of mostly single, binary or trinary star systems. But for right now, there are hundreds of them pretty tightly packed together, including an unusual concentration of stars more massive than our own!

So next time you're looking at the night sky, know that just 151 light years away, there are three or four hundred stars, all the same age, just waiting for you to discover them. But don't be fooled by Aldebaran; the orange giant is much closer, at only 65 light years away! Behind it? That's your nearest star cluster, the Hyades!

I thought Aldebaran was destroyed by the deathstar.

Deathstar ---> (=0=)>------- * <--- Aldebaran

@1 Alderann!

Isn't the Ursa Major Moving Group the nearest open cluster to Earth?

'course the problem with old open clusters is that they spread out with age and therefore you can't tell they're clusters any more.

Ahhh... thanks again for my daily fix... nothing better than coffee, fruit loops, and a nice cluster blog to start my morning off

@2 Alderaan

In the animation, Aldebaran is the bright star that moves rapidly from top to bottom. This nicely illustrates that its present alignment with the Hyades is only temporary.

I think my favourite open cluster is Messier 67, it has a similar age and metal content to the Sun. Wonder if any habitable planets could have survived in the cluster to the present day.

Ah, thank you Ethan, I love stereographic animations! For those who don't have the glasses, I found one of the Pleiades that uses the cross-eye technique (linked in my name).

The "Seven Sisters" thing always confused me, becuase I could only ever see six stars. If it's dark enough to see the 7th then you can probably see at least 10.

AB, bu konuda Åöyle bir beyanda bulunmuÅ, bir baÅka taraf Åöyle bir beyanda bulunmuÅ. Biz bunları dinleriz ama her ülkenin kendine has Åartları olduÄunu da gayet iyi biliyoruz. AB üyesi ülkelerde neyin nasıl çalıÅtıÄını da biz bugüne kadar gördük, görüyoruz. Åurada yanı baÅımızda AB, lütfen Yunanistanâdaki, Bulgaristanâdaki uygulamaları görsün ve bizim burada âorada uygulamalar böyle yapılıyorâ diye deÄil, onların çok ilerisine geçerek attıÄımız örnek adımlar var. Bu örnek adımları kimse görmüyor

linkspam above.

@3:

> Isn't the Ursa Major Moving Group the nearest open cluster to Earth?

Wikipedia says it's "the closest cluster-like object to Earth" ... maybe that means it's not an actual open cluster?

Ethan, I'm still not clear on how a star cluster's age affects the distribution of its stars on the HR diagram.

As the bigger, brighter stars burn out, the top of a cluster's distribution gets cut off, leaving the older, dimmer stars at the bottom. And the stars change color, so they leave the main sequence. So does the sequence of where clusters in that HR diagram peel off the main sequence indicate their relative age?

What's the deal with Persei, M41, M11, and NGC 752? Bunches of red giants and blue giants but nothing in between?

I thought Proxima Centauri was the closest star other than the sun of course?

One star does not a cluster make, Matt.

"Wikipedia says it's "the closest cluster-like object to Earth""

It's only cluster-like if you decide that it's just too darn big, Paul.

The stars still have a common motion, though they've nearly all broken free (hence not a very big cluster at all, 7 stars IIRC), so they're still a cluster.

I guess I'm really saying "I don't know why it's cluster-like rather than a cluster".

"I'm still not clear on how a star cluster's age affects the distribution of its stars on the HR diagram."

Stars sit at about the same spot on the HR diagram throughout their main sequence. The brighter a MS star is, the quicker it trots off the MS position and takes up its giant stage.

So an old cluster won't have OB stars at all, since they blew up long ago. A *very old* cluster won't have any A class stars. Extremely old clusters won't have F or G. And so on.

So a cluster ages, there are fewer blue stars, but the redder main sequence stars remain.

So the overall colour changes.

But an A class star doesn't move to an F class star. This may be where you're getting confused.

"What's the deal with Persei, M41, M11, and NGC 752? Bunches of red giants and blue giants but nothing in between?"

Note how rather than going diagonally from upper left to lower right, the line goes roughly horizontally. That is the line a population of giant off-MS stars take, where the brightness is indicative of the mass of the original, not the colour as happens with the main sequence.

The only stars that can still remain on the main sequence are stars that remain there for longer than ~5Bn years, so only the redder stars. All the ones bigger than that have blown up and moved to giant phase.

Rereading that seems a little clunky, but it's the best I can do at the moment.

The gap in the line is because main sequence will last billions of years roughly and their giant phase may last a good sized fraction of that again. The move from main sequence to giant stage can happen in years.

So that region isn't all that populated in a snapshot of star colour/size.

"But our nearest major star, alpha centauri, the yellow guy (below, found near the Southern Cross) is over four light years away from us. "

This is what I was talking about.

Glad you put M11 in there. My favorite target for my 8". Absolutely spectacular.

"This is what I was talking about."

Proxima is a brown dwarf. Barely a star. Note the "major star". I suspect another problem is that if he'd tried to describe Proxima, you'd have no chance finding what he's on about. Indeed, the star may not appear on the photo at all (making it impossible for you to see it in the picture).

Libyaânın yönetimi konusunda aÅiretlerin uzlaÅabileceÄi, birçok Arap ülkesinde de kuruluÅ aÅamasında aÅiret liderlerinin siyasi süreçte aktif rol oynadıÄı belirtildi.

1993 yılında aÅiret liderleri Kaddafiâye karÅı darbe giriÅimde bulunmuÅtu. Åubatâtan bu yana devam eden çatıÅmalar sırasında da Tuareg, Varfela, Migraha gibi aÅiretler Kaddafiâden desteÄini çektiÄini açıklamıÅtı

Ethan, I'm not sure if it's your thing stylistically, but as an astronomer I think you may enjoy this song:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1pI4YNLdLWU

Any rap that mentions Ursa Major and Ursa Minor is a good one in my book.

What would be like living on a planet orbiting a star within a close cluster like that? By that I mean; how far away are the stars from each other and would they have a direct effect on any orbiting bodies - such as light, heat or even pulling orbiting bodies from one star to the other.

It's unlikely that a globular cluster has enough metals to make a planet with a rocky surface, but if you moved one over there, a globular cluster has of the order of 100,000 stars in a region of the order of 30 light years across (30,000 cubic light years), so the average distance will be something less than 1 light year.

That's still a long way apart.

An open cluster has many fewer stars over a slightly smaller space and while a cluster is only a few score million years old and being tugged apart more by the stars outside the cluster than from within the cluster itself. The distance tends to be somewhat more than 1 light year.

Therefore orbits of any planets formed will not be any worse off than if there were no nearby stars.

Worse for any planet is being in a multiple star system unless well outside their common orbit and therefore very cold.