“Both the solutions must be rejected, and as these are the only statical solutions of the equations… the true solution represented in nature must be a dynamical solution.” -Willem de Sitter

First off, welcome, everyone! As you well know, the main Starts With A Bang blog has moved to Medium, something that's received mixed reviews from you, my longtime and most loyal of readers. Some people love the new layout, the larger images, and the ad-free experience, while others really miss the commenting features, the community we have here, and the ability to say whatever you like without a Twitter account.

Well, have I got some news for you: from today on, I've reached an agreement with both Medium and Scienceblogs, and new posts will continue at Medium, but for every new one posted there, I'll be posting a link to and a synopsis here, where you'll be able to comment and interact exactly as you're used to! So, without further ado, let's take a look at the biggest question of all!

Imagine, if you will, that our Earth wasn't like the Earth we're used to in only one important way.

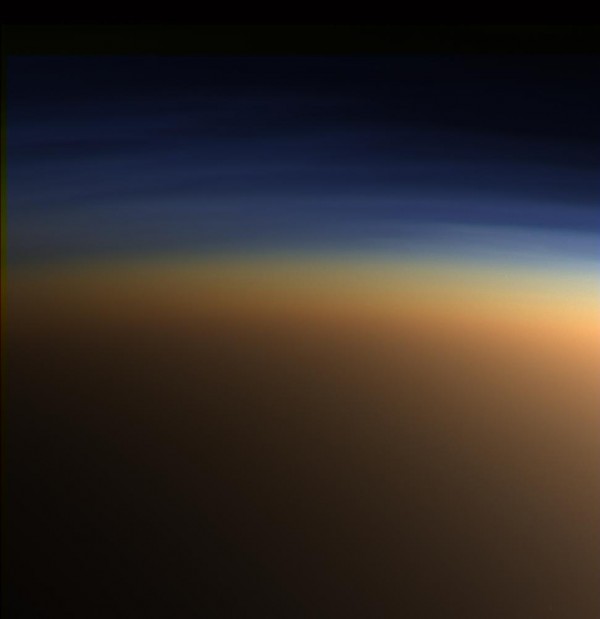

Rather than our atmosphere, where clouds may block light temporarily, but the heavens above are clearly visible on a pristine night, we had a view more akin to what someone who dwelled on Venus, Titan, or any of the gas giants would have: permanent cloud cover.

Image credit: NASA / Cassini Mission, via http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/jpeg/PIA06236.jpg.

Image credit: NASA / Cassini Mission, via http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/jpeg/PIA06236.jpg.

Imagine, if you will, that we still knew all the physics we presently know, but that we had never seen the stars, the night sky, or a deep view of the Universe. If suddenly, for the first time but without thousands of years of astronomical experience, we had access to those sights, would we be able to figure out where the entire Universe came from?

Would we arrive at the conclusion that the Universe started with the Big Bang? Or would other options seem just as plausible?

Go read the whole thing at Medium, and then weigh in below! (And I hope you like the new system!)

this first idea is essentially the same as the last but just a bit different it is very close

also under relativity space-time is expanding so this is essentially what we already imply to relativity its the fudge factor right ?

what is being proposed by many which i think is more logical is that the fabric's expansion or contraction is not the important part

but

the universal topology of the understood time component is maybe working differently from how we traditionally view it

maybe... there is more to it.

giving extra dimensions to time

so to say for example

the longer a thing/particle/wave travels a underlying component of it differs more and more from the tangent of time it was on , when it was emitted

that discrepancy is what is being picked up as the redshift

on observation

if we are to view the whole of everything moving thru time on a multi-dimension of time

i cant say how many dimensions would be needed for this

i imagine at least 3 maybe 4 or 5 , im not so good with math i wish i was ,

well from what i understand there are a few guys that are now working on this and trying to come up with a working way to look at it from this perspective, pretty cool

sorry if that was hard to read

sometimes i have a hard time conveying ideas and thoughts images into words that are clear

Ethan,

Thanks very much for making comments on your articles available to us old-fashioned types!

In your latest article, you write about the solar spectrum:

"All of these lines correspond to atoms in different states, and the thickest of these lines correspond to the elements hydrogen and helium, which are present in far greater abundance than all other elements combined."

Yes, it's true that the solar atmosphere is mostly hydrogen and helium .... but it's NOT true that the strongest absorption lines in the visible part of the spectrum are those of these two elements. Yes, the hydrogen lines are pretty strong, but the helium lines are very weak, and other elements -- iron and calcium in particular -- have very strong lines as well.

A young woman named Cecilia Payne figured out why there may be a big difference between the strongest absorption lines and the most common elements. Interested readers might start by reading

http://spiff.rit.edu/classes/phys301/lectures/comp/comp.html

and then moving to more technical materials, such as a good textbook on stellar atmospheres.

Michael,

You know, that's one of those frustrating things where I learned that just a few years ago -- about the strength of hydrogen but the weakness of helium -- and then promptly went back to my old (incorrect) way of thinking.

Thank you for the kind reminder on that point, and I should really be ashamed because I wrote on that point for myself less than a year ago. And yet I got it wrong here!

Let's hope it stays in the ol' noggin this time. :-)

Michael/Ethan, I'd always taken the weak signature of He as being why, despite being a small percent of the available mass, it isn't included in the "metallic" range of elements, as defined by astronomy: any element heavier than He.

I.e. a practical cutoff point.

I think once you understand general relativity, and I mean really understand it, you're into a situation wherein you're saying to yourself the universe just has to be expanding. Even if you can't see the stars and the galaxies. The amazing thing for me though, is why Einstein didn't come up with this.

Wow,

I think astronomers classify all elements beyond lithium as "metals", which is one more than you list. Lithium is the heaviest element produced in the big bang.

Pretty much all the lithium in the universe was produced in the big bang. It fuses very easily with deuterium to form two helium atoms so it gets burned up in stars. Fusion with a heavier nucleus like tritium or helium leads to the heavier elements.

I think this was discussed in Astronomy Cast #75

http://www.astronomycast.com/2008/02/ep-75-stellar-populations/

which I have found to be a fun podcast to listen to and learn more about astronomy.