“Dwell on the beauty of life. Watch the stars, and see yourself running with them.” -Marcus Aurelius

Let there be light! You'd think that would be enough: that you form stars in the Universe, you see those stars in the Universe, and that tells you about what's out there.

If only it were that simple.

Image credit: ESO, via http://www.eso.org/public/images/eso0102a/.

Image credit: ESO, via http://www.eso.org/public/images/eso0102a/.

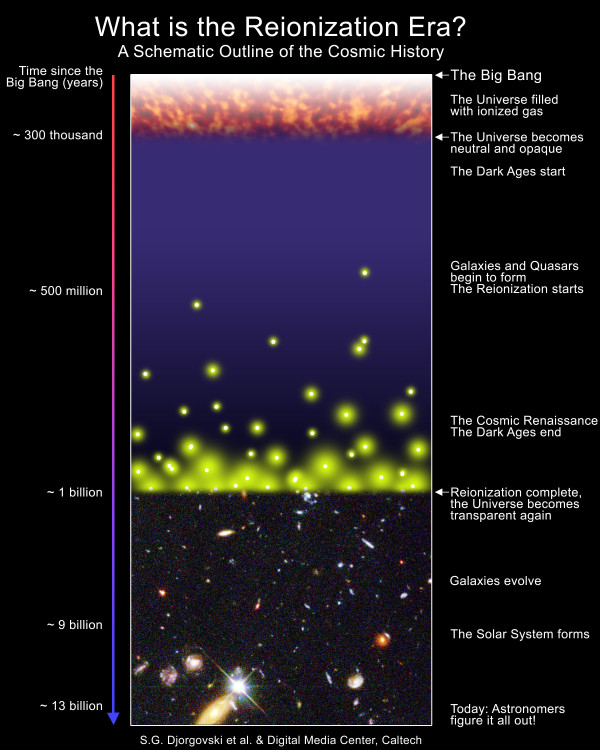

In order to truly see the first stars, you need a lot more that just starlight: you need that light to be able to freely travel through space. And -- as bad luck would have it -- visible light, the kind of light we've built our telescopes to see, is opaque to neutral atoms.

In other words, it's not enough to simply have a Universe full of stars; you need a transparent Universe full of stars, otherwise they'll be invisible to our eyes!

Are the first stars in the Universe truly invisible? Find out -- and get the full story -- here!

Ethan, I'm having a bit of a problem with the later parts of your article. The problem is Z. For the period of the Dark Ages, more than 13 billion years ago, Z > 10. That pushes visible light down into the mid-infrared, which unfortunately is exactly where JWST is optimized. So it's going to be looking for redshifted light which _was_visible_light_ during the Dark Ages, and therefore would have been absorbed by the neutral-atom universe.

So there shouldn't be anything for JWST to see, just as there's nothing for us to see now (because the UV, now redshifted into visible, was also being absorbed by all those neutral atoms as they got slowly ionized).

What an interesting question. Since we can see the evolution of galaxies, etc. in the present (near past), then anything prior has already passed us by, according to the chart of cosmic history above. Or has it? Light from closer bodies gets here before that of more distant objects, so, could that imply the distant past has not arrived yet for us to see? In which case, the light of the first stars could be in any time zone (near, to far). So, we may have seen the extinction of early stars already in supernovae & other such phenomena. Ouch, my head hurts!

Isn't a large part of the explanation the fact that expansion (which is a stretching of the space the electromagnetic waves are moving in) has resulted in much of visible light waves from the early days of the universe being stretched out into longer, non-visible wavelengths over time?

@Marc Greer #3: That's the same point I was making. I was hoping that Ethan will find time to reply, either here or in "comments of the week", but that didn't happen.