"I have worn myself thin trying to find out about this comet, and I know very little now in the matter." -Maria Mitchell

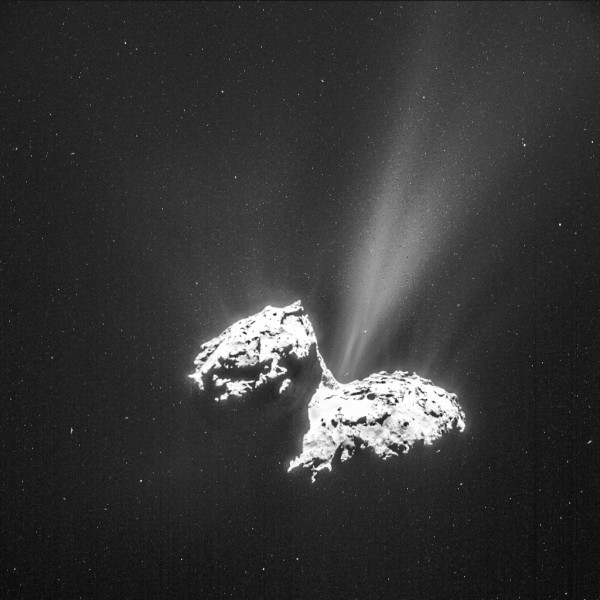

Originating from the Kuiper belt and the Oort cloud, comets are generally thought of as periodic objects, with their initial trajectories having been perturbed by either Neptune, another distant object or a passing star or rogue planet.

But most comets aren't periodic; they're transient instead, where a trip into the inner Solar System gives them additional gravitational perturbations, causing them to either fly into the Sun or gain enough kinetic energy to escape entirely. This latter fate is the case for Comet Catalina, which reaches perihelion on November 15th and then heads out of the Solar System after putting on one final show for observers on Earth.

Learn how to see it, where to find it and why it's on its way out!

Ethan -

People always refer to passing stars disturbing our Oort cloud and launching a comet Sun-ward. What about the Sun disturbing other stars' clouds and drawing off one or more of their Oortlets? We must be near the edge of the Centauri system's cloud.

Could we detect such a catch from the comet's path? I'm thinking that if it were to get close enough for us to observe it, it would most probably be an extremely elongated ellipse, as a hyperbolic path seems unlikely to enter the inner solar system.

If we ever do spot one, what a chance to get a look at someone else's history. We should be able to use isotopic analysis to determine whether the stars were born from the same primal cloud.

With a star 4-8 light years away, and an Ooort cloud about 0.1 light years away, the chances of getting OUR Oort cloud ejector is 40^2-80^2 times more likely to happen than us getting theirs.