"'I'll follow him to the ends of the earth,' she sobbed. Yes, darling. But the earth doesn't have any ends." -Tom Robbins

We have some pretty good definitions of what it takes to be a planet, and one part of that definition is that a world needs to be massive enough to pull itself into hydrostatic equilibrium. In the absence of external forces and rotation, that means it will be a perfect sphere.

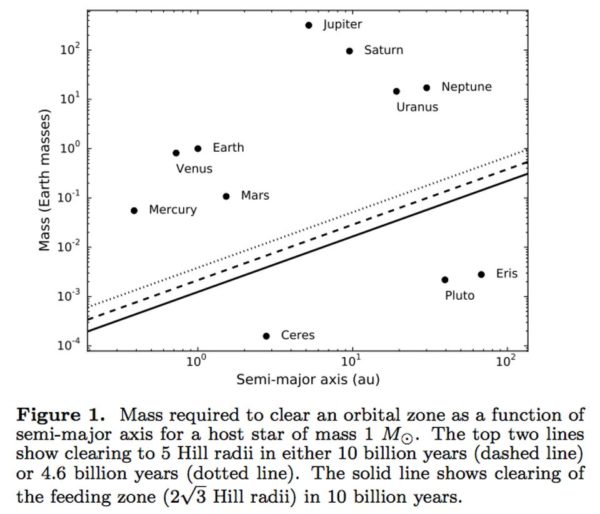

The line for a planet vs. a non-planet is mass-dependent, and making a thin, rigid body fails on that account. You can have a flat "thing" in space, but it wouldn't be a planet if you did. Image credit: Margot (2015), via http://arxiv.org/abs/1507.06300.

The line for a planet vs. a non-planet is mass-dependent, and making a thin, rigid body fails on that account. You can have a flat "thing" in space, but it wouldn't be a planet if you did. Image credit: Margot (2015), via http://arxiv.org/abs/1507.06300.

But what about if you allow the other forces to come into play? In addition to the many interesting features you'll get, one of them is a flattening of your world. So that brings up the question of how flat a planet could possibly be? This isn't just theory; our own Solar System has a great example that you'll want to see for yourself!

That's why you build a ringworld. :) or maybe just an Ian Banks-type orbital.

Figure 1 is very striking in terms of how well it separates the planets from the dwarf planets (or whatever you want to call them). However, The three lines seem somewhat arbitrarily added. For one they change the years and another they change the radii cleared? How is that consistent or a good standard? Also I don't know the subject well enough to know whether the proposers put the centerline where it is using some empirical best fit (to a sample size of 'one solar system') or some more sound theoretical basis, but I hope its the latter. If so, please elucidate!

@eric #1: I highly recommend going and reading the paper from which Ethan extracted that figure (cited in the caption, http://arxiv.org/abs/1507.06300).

Those lines are NOT the IAU specification. They are examples showing that if you vary the two parameters (duration and distance) significantly, the separatrix does not actually change substantially.

The choices are not "arbitrary," but well motivated as exemplars. For the duration of possible orbital clearing, 4.6 Gy corresponds to our own solar system, while 10 Gy corresponds, for example, to a plausible exoplanet system around a red dwarf star which formed early in the Milky Way.

For the "clearing radii", the Hill sphere is the maximum volume around some mass where another, larger mass can't capture stuff away. For the Earth, for example, its Hill sphere is the region where satellites can't be perturbed out of orbit by the Sun. Five times that distance is a pretty good large space for which you might expect a "planet" (a big ol' standalone object) not to have a bunch of stuff carried along with it. It's also small enough to exclude the special three-body capture zones like the Lagrangian points, where Trojan asteroids collect.

Michael, thank for the response. As an example of how widely the parameters can vary and the separation still holds, it makes sense.

Two-dimensional... If you're a Republican.

You could start with a slow rotating, liquid covered planet that was tectonically inactive, and through gravitational interaction with another body kick it out of the solar system or into a higher orbit so that the liquid cover froze solid. Queball planet.

It seems that you could also accomplish it via erosion.

In science fiction, the world Mesklin (Hal Clement, _Mission of Gravity_) was very flat -- about 3.9 to 1.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mesklin