Brains

I've got this press release that will be of interest to many:

An international team including researchers at the university of Edinburgh and Antoine Wystrach of the Research Centre on Animal Cognition (CNRS/Université Toulouse III—Paul Sabatier) has shown that ants can get their bearings whatever the orientation of their body. Their brains may be smaller than the head of a pin, but ants are excellent navigators that use celestial and terrestrial cues to memorize their paths. To do so, they use several regions of the brain simultaneously, proving once again that the brain of insects is more…

In 1817, Karl August Weinhold had a go at a real-life Frankenstein's monster -- only in his version he uses a cat. The German scooped out the brain and spinal cord of a recently dead cat. He then pured a molten mixture of zinc and silver into the skull and spinal cavity. He was attempting to make the two metals work like an electric pile, or battery, inside the unfortunate cate, replacing the electrical of the nerves. Weinhold reported that the cat was revived momentarily by the currents and stood up and stretched in a rather robotic fashion!

It's Alive!!!!

Weinhold's reanimated cat was…

Recently, I mentioned two new books on human evolution, and I told you I had a print review of them coming up.

Well, it's here, in American Scientist!

Yes, I know, that's an internet thing, but it is the internet version of the print thing. Please have a look, and leave a nice comment! Or a mean comment, whatever.

Many people assume human brains vary genetically and genetic variation maps to races. But the races are not real and genetic variation can't explain brain differences. Because, dear reader, brains don't work that way.

Let's look just at the brain part of this problem.

There are between 50 and 100 billion neurons in the human brain, and every one is connected to a minimum of one other neuron to produce about 100 trillion connections. So when we are thinking about how the brain is wired up, we have to explain how so many connections can be specified to make the brain work.

There are…

This article is reposted from the old Wordpress incarnation of Not Exactly Rocket Science.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is the most common developmental disorder in children, affecting anywhere between 3-5% of the world's school-going population. As the name suggests, kids with ADHD are hyperactive and easily distracted; they are also forgetful and find it difficult to control their own impulses.

While some evidence has suggested that ADHD brains develop in fundamentally different ways to typical ones, other results have argued that they are just the result of a delay in the…

Artificial Intelligence as a term implies that there is a "natural" intelligence we wish to replicate in the lab and then engineer in any one of several practical contexts. There is nothing in the term that implies that "intelligence" be human, but the implication is clear that such a thing as "intelligence" exists and that we have some clue as to what it is.

But it might not, and we don't.

Read the rest here...

Dawkins gave a talk that could be criticized as not particularly new, in that his main idea is that human brains are too powerful and adaptable to continue to function primarily within an adaptive program serving as a proper adaptive organ. Instead, human brains think up all sorts of other, rather non-Darwinian things to do. This idea has been explored and talked about in many ways by many people. Kurt Vonegut Jr.'s character in Galapagos repeatedly, in a state of lament, quips "Thanks, Big Brain..." as evidence accumulates that our inevitable march towards extinction is primarily a…

The male and female human brains are different. Some of the better documented differences are similar to differences seen in other mammals. They are hard to find, very small, and may or may not be of great significance. Obviously, some are very important because they probably relate to such things as the ability ... or lack thereof ... to bear offspring. But this is hardly ever considered in the parodies we see of these differences.

[Repost from Gregladen.com]

You have all seen the sometimes funny, sometimes not cartoon depictions of these differences, for example this one:

Obviously,…

The blood that flows into our heads is obviously important for it provides nutrients and oxygen to that most energetically demanding of organs - the brain. But for neuroscientists, blood flow in the brain has a special significance; many have used it to measure brain activity using a technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI.

This scanning technology has become a common feature of modern neuroscience studies, where it's used to follow firing neurons and to identify parts of the brain that are active during common mental tasks. Its use rests on the assumption that the…

I've been pretty quiet on the blog while I've been off visiting grandparents in other states this past week. But in the meantime, Slate has published a piece I wrote for them on the beguiling mystery of octopus brains. I wonder if this guy would find it enlightening.

Update: A couple readers pointed out to me that I should have said octopuses jet water, not air. Sorry for the slip--it should be fixed shortly.

A couple weeks ago I spoke at Downstate Medical Center in New York about some of my articles in the New York Times that revolve around how the mind evolved. We can learn from bacteria, fruit flies, hyenas, and our own kids. You can now see the whole lecture with surprisingly clear slides on blip.tv. Click on the screen below, or go to the page on blip.tv. Warning: the sound drops out briefly around 13:00.

Brought to you by Max Cannon, creator of Red Meat and also the dude who helps run the awesome independent Loft Cinema here in Tucson:

Hilarious...

Also, if you haven't caught it yet, don't forget to check out this week's Carnival of Space, where we have an entry about actually seeing a supernova go off.

Today on bloggingheads, I talk to Gary Marcus, NYU psychologist and author of the new book Kluge, about all the telling ways in which our minds let us down, and what those shortcomings tell us about how it evolved.

A new map of some of the connections neurons make in the frontal cortex of a monkey's brain. From PLOS Computational Biology. Bigger image here.

My newest "Dissection" column is up at Wired.com. This time around, I take a look at how our brains relay signals. They turn out to do a terrible job. What's impressive is how they clean up their own mess. Check it out.

[Image via Vesalius Gallery]

(update 4.4.08 9:30 am: link fixed)

When one of the founders of cognitive neuroscience is helping you plumb the mysteries of consciousness, the self, free will, and the two minds that coexist in our skulls, it helps every now and then to touch your nose. To understand why touching your nose is such a profound experience, check out my talk today on bloggingheads with Mike Gazzaniga.

(And if you want to see what Mike was like as a young post-doc 50 years ago, check out this video from the early1960s about his split brain research. It's also evidence of how much science documentaries have changed...)

For years, fellow scienceblogger PZ Myers has taught us all well why we ought to adore squid, octopuses, and other cephalopods. But I came to a new degree of appreciation when I traveled up to Woods Hole to spend some time with the biologist Roger Hanlon. Hanlon studies how cephalopods disguise themselves, and boy do they ever. Right in front of your eyes, sitting in a little tub of water, the animals can practically disappear. Or, if they want to scare you, they turn a chocolately brown with bright stripes.

After my visit, I wrote a profile of Hanlon, which is the lead article in tomorrow's…

My fellow bloggingheads John Horgan and George Johnson took some time on their latest science talk to dissect my New York Times article on swarms (you can jump to that section here). John wonders if I'm just discovering all the complexity stuff he and George were writing about back in the 1990s. I think it's always good for John to keep everyone aware of the dangers of hype, of the need to ask how important or new scientific research really is. He's been particularly tough on the science of complexity, if there is such a thing. In 1995 he wrote a piece in Scientific American that practically…

Not much blogging this week--I'm heading out to California to receive the National Academies prize I wrote about a while back. In the meantime, let me direct your attention to my lead article in this week's Science Times section of the NY Times. I wrote about swarms, herds, schools, gaggles, and other crowds of animals, focusing on one of the scientists who studies them, Iain Couzin. If you want to find out more about his quest to find the underlying rules of swarm intelligence, check out his web site.

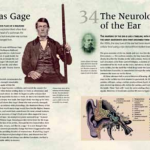

It's a brave new world for us book authors. Today's case in point: PZ Myers assigned some of his students to ready my book Soul Made Flesh, which chronicles how humanity figured out what the brain is for. Some of his students have bravely agreed to post their reports on the book on Myers's blog Pharyngula (here and here). The comment thread has turned into a wide-ranging book-club discussion. I'm chiming in from time to time too (here and here, for example). I'm definitely enjoying it and will check in as long as the discussion goes.