History of Science

The stupid Steven Pinker business from a few weeks ago turned out to do one good thing after all. It led to this post at Making Science Public, which quoted some books by Jacob Bronowski that sounded relevant to my interests. And, indeed, on checking The Common Sense of Science out of the college library, I opened it up to find him making one of the arguments of my book for me:

Many people persuade themselves that they cannot understand mechanical things, or that they have no head for figures. these convictions make them feel enclused and safe, and of course save them a great deal of trouble…

Two chapters of the book-in-progress will be devoted to the development of the modern understanding of the atom. One of these is about the Bohr model, which turned 100 this year, but Bohr's model would not have been possible without an earlier experiment. The actual experiment was done by Ernest Marsden and Hans Geiger, but as is the way of such things, the historical credit mostly accrues to their boss and noted force of nature, Ernest Rutherford. This is the experiment that established the cartoon image of an atom as a solar system, which is utterly unworkable using classical physics, and…

I've been revising a chapter on collaboration in science for the book-in-progress, making an analogy to team sports. And it occurred to me as I was trying to find a way to procrastinate, that while science is a highly collaborative endeavor, most of the popular stories that get told about science are not. There's no Hoosiers of science out there.

Now, admittedly, the sample of great pop-culture stories about science period is pretty small. But what does exist mostly concerns individual struggles-- the lone genius who can revolutionize science by just thinking about it in isolation, but who…

Adam Frank has an op-ed at the New York Times that tells a very familiar story: science is on the decline, and we're living in an "Age of Denial".

IN 1982, polls showed that 44 percent of Americans believed God had created human beings in their present form. Thirty years later, the fraction of the population who are creationists is 46 percent.

In 1989, when “climate change” had just entered the public lexicon, 63 percent of Americans understood it was a problem. Almost 25 years later, that proportion is actually a bit lower, at 58 percent.

The timeline of these polls defines my career in…

I'm writing a bit for the book-in-progress about neutrinos-- prompted by a forthcoming book by Ray Jaywardhana that I was sent for review-- and in looking for material, I ran across a great quote from Arthur Stanley Eddington, the British astronomer and science popularizer best known for his eclipse observations that confirmed the bending of light by gravity. Eddington was no fan of neutrinos, but in a set of lectures about philosophy of science, later published as a book, he wrote that he wouldn't bet against them:

My old-fashioned kind of disbelief in neutrinos is scarcely enough. Dare I…

Via a retweeted link from Thony C. on Twitter, I ran across a blog post declaring science a "bourgeois pastime." The argument, attributed to a book by Dierdre McCloskey is that rather than being at the root of economic progress, scientific advances are a by-product of economic advances. As society got more wealthy, it was able to direct more resources to science, which made great advances possible.

And, you know, if you're looking to make a bold and contrarian argument, you can certainly do that. Unfortunately, the bit quoted from McCloskey as an illustration of the power of the argument is:…

I'm doing edits on the QED chapter of the book-in-progress today, and I'm struck again by the apparent randomness of the way credit gets attached to things. QED is a rich source of examples of this, but two in particular stand out, one experimental and the other theoretical.

On the experimental side, it's interesting to note that one of the two experimental effects that really galvanized the theoretical effort leading to QED bears the name of a particular person, while the other does not. Ask any physicist about the origin of QED, and they will almost certainly be able to cite the "Lamb shift…

There was another round of the "who counts as a scientist?" debate recently, on Twitter and then on the Physics Focus blog. In between those, probably coincidentally (he doesn't mention anything prompting it), Sean Carroll offered a three-step definition of science:

Think of every possible way the world could be. Label each way an "hypothesis."

Look at how the world actually is. Call what you see "data" (or "evidence").

Where possible, choose the hypothesis that provides the best fit to the data.

This isn't quite the way I would put it-- I'm an experimentalist where Sean's a theorist, so I…

One of the oddities of writing the book-in-progress is that it involves a lot more history-of-science than I'm used to. which means I'm doing things like checking out 800-page scientific biographies from the college library so I can use them to inform 500 word sections of 4000 word chapters. One of these is Cavendish: The Experimental Life by Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach, a biography of Henry Cavendish (and his father), whose most famous experiment is one of the things I plan to describe in the book. Henry himself turns out to be quite a character, though, thus the 800-page…

I've got a ton of stuff that needs to get done this week, but I don't want the blog to be completely devoid of new content, so here's a quasi-poll question for my wise and worldly readers:

What scientist is most in need of a good popular biography?

By "popular biography," I mean things like Norton's Great Discoveries books, several of which Ive reviewed here, including Krauss on Feynman and Reeves on Rutherford, two books that I keep coming back to for useful tidbits. These aren't deep works of historical scholarship, and don't necessarily attempt to be definitive, but focus on being…

A little while back, I posted about the pro-theorist bias in popular physics, and Ashutosh Jogalekar offers a long and detailed response, which of course was posted on a day when I spent six hours driving to Quebec City for a conference. Sigh.

Happily, ZapperZ and Tom at Swans On Tea offer more or less the response I would've if I'd had time and Internet connectivity. Tom in particular gives a very thorough exploration of some of the reasons why experiment gets downplayed in popular physics. I particularly liked this bit:

I’m going to put forth a possibility: maybe we have a harder job, in…

I mentioned on Twitter that I was thinking of proposing a Science Online program item about the professionalization of blogging, throwing in a link to post from a couple months ago. That included a link to this SlideShare:

Talking to My Dog About Science: Why Public Communication of Science Matters and How Social Media Can Help from Chad Orzel

And that was re-tweeted by Chris Chabris, kicking off a gigantic conversation about the whole idea of scientists communicating directly with the public (most of which took place after I went to bed last night, so I only saw it in my Twitter…

While we're revisiting blog topics of the recent past, another item from this weekend's visit to the Ithaca Sciencenter, in the form of the picture above. For those with images off, or who read via RSS and won't see the picture, it's a photo of one of the inspirational plaques they have lining the walls of their community room, honoring famous scientists. This particular one is for Richard Feynman, and what struck me about it was that the photo isn't his Nobel Prize portrait, or him playing the bongos, but a somewhat grainy picture of him standing next to a telescope in the desert, pushing a…

At Scientific American's blog network, Ashutosh Jogalekar muses about the "greatest American physicist", eventually voting for Josiah Willard Gibbs, one of the pioneers of statistical mechanics. As both times I took StatMech (as an undergrad and in grad school), it was at 8:30 in the morning, I retain almost no memory of the subject, and will bow to greater experience in assessing Gibbs's importance.

I do, however, want to take issue with one thing in the post. When assessing the historical place of American physics, he writes:

Here’s my personal list for the title of greatest American…

The book-in-progress (which is coming along, albeit slowly, thanks for asking) is built around making analogies between scientific discoveries and ordinary activities. This necessarily means telling a lot of historical stories, which is both good and bad. The bad part is that actual history is way messier than the streamlined version you get to use if you're primarily trying to explain the science, and I feel some obligation to do this right as much as possible, thus making work for myself. The good part is I'm reading a lot of narrative history of science stuff, which is kind of fun. In…

Erwin Schrödinger is one of the more colorful figures in physics history. He's best known for Emmy's favorite thought experiment, of course, which attempts to demonstrate the absurdity of quantum physics through locking a cat in a box. This overshadows the Schrödinger Equation, the central equation of non-relativistic quantum mechanics, which won him a Nobel Prize in 1933. He's also renowned within physics for his unorthodox personal life, which involved innumerable extramarital affairs, and ultimately cost him a job at Oxford.

The definitive academic biography of Schrödinger has been out for…

I was re-reading bits of James Gleick's Feynman biography, and ran across a bit near the end (page 397 of my hardcover from 1992) talking about his relationship with his children, talking about how ordinary he seemed at home.I particularly liked the sentence "Belatedly it dawned on them that not all their friends could look up their fathers in the encyclopedia." It occurred to me that that would be a good line for an obituary.

This is not due to any particularly morbid cast of mind on my part, but lingering blowback from the kerfuffle over the New York Times obituary for Yvonne Brill a couple…

I ran across this recently while looking for something else, and was reminded of it by this discussion of jargon. It's an attempt to explain the general historical context of the whole Higgs Boson thing, and why it's important. I improvised this in response to somebody's question about how I would explain that, drawing mostly on my recollection of a couple of history-of-field-theory books. I kept it in case I needed to bust it out when they discovered the Higgs, but that fell during the time when I wasn't able to blog, so I never used it. I'm never going to use it for anything else, though,…

While in the library looking for something else, I noticed a book called The Trouble with Science by Robin Dunbar, whose description made it sound very much on point for my current project:

In The Trouble with Science, Robin Dunbar asks whether science really is unique to Western culture, even to humankind. He suggests that our "trouble with science"--our inability to grasp how it works, our suspiciousness of its successes--may lie in the fact that evolution has left our minds better able to cope with day-to-day social interaction than with the complexities of the external world.

Somewhat…

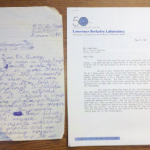

I have mentioned before that when I was a kid, I wrote a letter to Luis Alvarez, the 1968 Nobel laureate in Physics, asking some questions about his theory that an asteroid impact killed the dinosaurs, which had been featured in a NOVA special. I got a very nice letter back from him, very graciously correcting the dumber questions I asked. This made a very favorable impression, which in turn played a role in getting me to include him in the work-in-progress.

Since I was thinking about Alvarez for the book, I asked my parents if they still had a copy of the letter, which for many years I had…