Theory

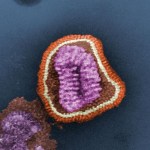

The Twitter conversation that prompted yesterday's post about composite objects was apparently prompted by a comment somebody made about how a virus left alone would see its quantum wavefunction spread out on a time scale of minutes. This led to wondering about whether a virus could really be considered a particle that would move as a single quantum unit, and then to whether that estimate is reasonable. So, let's look at that specific question a little more closely. This is going to be one of those swashbuckling physicist estimation deals, in which I'm going to attempt to come up with numbers…

Through some kind of weird synchronicity, the title question came up twice yesterday, once in a comment to my TED@NYC talk post, and the second time on Twitter, in a conversation with a person whose account is protected, thus rendering it un-link-able. Trust me.

The question is one of those things that you don't necessarily think about right off-- of course an atom is a particle!-- but once it gets brought up, you realize it's a little subtle. Because, after all, while electrons and photons are fundamental particles, with no internal structure, atoms are made of smaller things. But somehow we…

We cleared a bunch of space in our deep storage area over the summer, and one of the things we found was a box full of old student theses from the 1950's and 1960's. The library already had copies of them, but I thought it was sort of cool to have a look into the past of the department, so we put them up on a shelf in the office. Yesterday, I was glancing over this, and spotted a thin volume, pictured in the "featured image" above, which was a Master's thesis from 1960 (when we used to give MS degrees in physics...) titled "A Monte Carlo Study of Neutron Scintillation Detection with a…

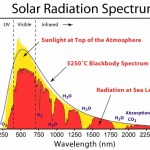

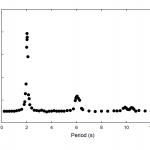

I'm putting together slides for a TED audition talk in a couple of weeks, about how the history of quantum mechanics is like a crossword puzzle. This involves talking about black-body radiation, which is the problem that kicked off QM-- to explain the spectrum of light emitted by hot objects, Max Planck had to resort to a mathematical trick: he assumed that the objects were composed of "oscillators" that emitted light in discrete amounts, with the energy of the emitted light proportional to the frequency of the light. This was a desperation move, and made him a little crazy:

Max Planck…

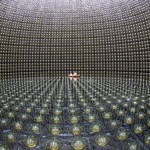

One of the chapters of the book-in-progress talks about neutrino detection, drawing heavily on a forthcoming book I was sent for blurb/review purposes (about which more later). One of the little quirks of the book is that the author regularly referred to physicists trying to "trap" neutrinos. It took me a while to realize that he just meant "detect"-- coming from the AMO community, I naturally assume that "trap" means "localize to a small-ish region of space for a long-ish period of time." That is, after all, what I spent my Ph.D. work doing-- trapping cold atoms.

SteelyKid had a rough…

Two chapters of the book-in-progress will be devoted to the development of the modern understanding of the atom. One of these is about the Bohr model, which turned 100 this year, but Bohr's model would not have been possible without an earlier experiment. The actual experiment was done by Ernest Marsden and Hans Geiger, but as is the way of such things, the historical credit mostly accrues to their boss and noted force of nature, Ernest Rutherford. This is the experiment that established the cartoon image of an atom as a solar system, which is utterly unworkable using classical physics, and…

When I wrote up the giant interferometer experiment at Stanford, I noted that they've managed to create a situation where the wavefunction of the atoms passing through their interferometer contains two peaks separated by almost a centimeter and a half. This isn't two clouds of atoms each definitely in a particular position, mind, this is a wavefunction representing a bunch of atoms that are each partly in two places at the same time , separated by 1.4 centimeters.

I emailed Mark a link to the post, and in his reply he said that they've increased that to about 4cm (which is just a matter of…

I'm writing a bit for the book-in-progress about neutrinos-- prompted by a forthcoming book by Ray Jaywardhana that I was sent for review-- and in looking for material, I ran across a great quote from Arthur Stanley Eddington, the British astronomer and science popularizer best known for his eclipse observations that confirmed the bending of light by gravity. Eddington was no fan of neutrinos, but in a set of lectures about philosophy of science, later published as a book, he wrote that he wouldn't bet against them:

My old-fashioned kind of disbelief in neutrinos is scarcely enough. Dare I…

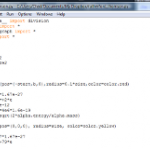

Some time back, I spent a bunch of time writing a VPython program that simulated the motion of a pendulum, which turned out to do some strange things. In the comments to that, there were two things worth mentioning: first and foremost, Arnoques at #5 spotted a small error in the code that fixes the odd behavior noted in that post-- when I corrected it, the stretch needed to keep the pendulum swinging smoothly without oscillating in and out along the string was exactly what you would expect (the "factor" plotted in that earlier post is infinitesimally smaller than 1.0-- I got bored trying to…

I'm doing edits on the QED chapter of the book-in-progress today, and I'm struck again by the apparent randomness of the way credit gets attached to things. QED is a rich source of examples of this, but two in particular stand out, one experimental and the other theoretical.

On the experimental side, it's interesting to note that one of the two experimental effects that really galvanized the theoretical effort leading to QED bears the name of a particular person, while the other does not. Ask any physicist about the origin of QED, and they will almost certainly be able to cite the "Lamb shift…

One thing I left out of the making-of story about the squeezed state BEC paper last week happened a while after publication-- a few months to a year later. I don't quite recall when it was-- I vaguely think I was still at Yale, but I could be misremembering. It's kind of amusing, in an exceedingly geeky way, so I'll share it, though it's also a story of an embarrassing mis-step on my part.

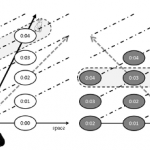

So, the physical situation we were studying is described by the "Bose-Hubbard Hamiltonian": Bose because it's dealing with bosons (there's also a Fermi-Hubbard version, I believe); Hubbard after [mumble]…

I spend a lot of time promoting Rhett Allain's Dot Physics blog, enough that some people probably wonder if I get a cut of his royalties (I don't). I'm going to take issue with his latest, though, because he's decided to revive his quixotic campaign against photons, or at least teaching about photons early in the physics curriculum. We went through this back in 2008 and 2009 (though Rhett's old posts are linkrotted away, so you only get my side of the story...). I'm no more convinced this time around, even though he drags in Willis Lamb and David Norwood for support.

There are basically two…

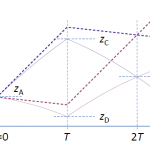

In the Physics Blogging Request Thread the other day, I got a comment so good I could've planted it myself, from Rachel who asks:

It’s a term I see used a lot but don’t really know what it means – what is a “squeezed state”? What does “squeezing” mean? (in a QM context of course…)

I love this, not only because it gives me an excuse to talk about cool physics, but because it will let me engage in blatant self-promotion-- I have a Science paper on squeezed states, which I've never actually written up for the blog. So this post will be a great way to set up a future post, ResearchBlogging that…

A few months back, I got a call from a writer at a physics magazine, asking for comments on a controversy within AMO physics. I read a bunch of papers, and really didn't quite understand the problem; not so much the issue at stake, but why it was so heated. When I spoke to the writer (I'm going to avoid naming names as much as possible in this post, for obvious reasons; anyone I spoke to who reads this is welcome to self-identify in the comments), he didn't really get it, either, and after kicking it around for a while, it failed to resolve into a story for either of us-- in his case, because…

A little while back, I posted about the pro-theorist bias in popular physics, and Ashutosh Jogalekar offers a long and detailed response, which of course was posted on a day when I spent six hours driving to Quebec City for a conference. Sigh.

Happily, ZapperZ and Tom at Swans On Tea offer more or less the response I would've if I'd had time and Internet connectivity. Tom in particular gives a very thorough exploration of some of the reasons why experiment gets downplayed in popular physics. I particularly liked this bit:

I’m going to put forth a possibility: maybe we have a harder job, in…

Last week, I spent a bunch of time using VPython to simulate a simple pendulum, which was a fun way to fritter away several hours (yes, I'm a great big nerd), and led to some fun physics. I had a little more time to kill, so I did one of the things I mentioned as a possible follow-on, which turned out to be kind of baffling, in a good way.

Last week's post was written very quickly, and thus ended up a little more jargon-y than I usually shoot for, so let me try to set the stage a little better for this one. the physical system I'm talking about is just a simple pendulum, a mass on the end of…

At Scientific American's blog network, Ashutosh Jogalekar muses about the "greatest American physicist", eventually voting for Josiah Willard Gibbs, one of the pioneers of statistical mechanics. As both times I took StatMech (as an undergrad and in grad school), it was at 8:30 in the morning, I retain almost no memory of the subject, and will bow to greater experience in assessing Gibbs's importance.

I do, however, want to take issue with one thing in the post. When assessing the historical place of American physics, he writes:

Here’s my personal list for the title of greatest American…

My parents have a DVD of the Bacon Brothers singing "The Wheels on the Bus" over an animated scene, which The Pip loves and insists on watching over, and over, and over, and over... As the parent sitting through this on Sunday morning, I got a little punchy over on Twitter, and invented some quantum-physics-themed verses (if you don't know the tune, 1) count yourself lucky, and 2) here's a clip from the video on YouTube). Here are the results:

The electrons on the bus are fermions,

fermions,

fermions.

The electrons on the bus are fermions, in antisymmetric states...

Operators on the bus are…

Last year, Alan Alda posed a challenge to science communicators, to explain a flame in terms that an 11-year old could understand. this drew a lot of responses, and some very good winners. This year's contest, though still called the "Flame Challenge," asked for an answer to the question "What Is Time?"

This is a little closer to my corner of science, so I considered entering, but as previously noted, I'm crushingly busy at present. And either scripting/ shooting/ editing a video, or doing the necessary work to hack a written response down to the prescribed 300 characters was more time than I…

For something related to the book-in-progress, I was reading Raymond Chandler's classic essay "The Simple Art of Murder" last night, and stumbled across the following quote, where he laments the number of stories in print in the mystery genre in 1950:

In my less stilted moments I too write detective stories, and all this immortality makes just a little too much competition. Even Einstein couldn’t get very far if three hundred treatises of the higher physics were published every year, and several thousand others in some form or other were hanging around in excellent condition, and being read…