“The public, blog-fueled controversy over the utilization of arsenate instead of phosphate in bacteria was, in the end, a demonstration of what is truly right with scientific quests,” says Prof. Dan Tawfik. “The original findings (that certain bacteria can use arsenate instead of phosphate) may have been overhyped. The research itself may have been underwhelming. But what ensued is exactly what should have happened: The correcting mechanisms that are intrinsic to science kicked in. Other experimental groups examined the claims in their labs and found them to be unsupported. And new scientific questions arose in their wake. All in all, some very good science came out of those questionable findings.”

Tawfik and postdoc Dr. Mikael Elias should know. Their recent study might settle the arsenate debate once and for all. But their work also turns out to be a powerful demonstration of evolutionary fine-tuning in proteins that function in an inhospitable environment.

On the face of it, the original claim was convincingly put: The bacteria in question live in lake sediment with a high arsenate content. Since arsenate is chemically nearly identical to phosphate, it might almost stand to reason that these microorganisms have evolved to substitute the normally toxic substance for the phosphate that all known life forms use to build DNA and other vital metabolic compounds. But, say Tawfik and Elias, phosphate's unique chemical properties are so basic to life that such bacteria would pretty much have to reinvent biochemistry (Others have since shown that these bacteria do, indeed, rely on phosphate, alone.)

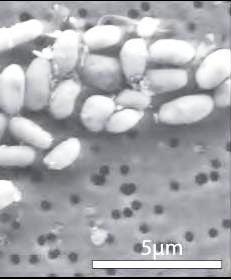

And yet, a niggling question remained: How do the bacterial proteins responsible for taking up phosphate from the environment manage to select the desired molecule and avoid picking up the toxic arsenate instead? Tawfik and Elias had their first clue when they compared the function of this protein in several different bacterial species – some that routinely live with arsenate and others that don’t. It turns out that the phosphate import machinery of all bacteria they tested is pretty good at selecting phosphate over arsenate. But those that make their home in arsenate-filled sediments are really proficient: The chances that they’ll accidentally pick up an arsenate molecule are less than one in 5000. So, instead of adapting by making use of the environmental arsenate, these bacteria have actually evolved to reject it ever more efficiently.

Further research (including a crystallization technique that enabled the researchers to resolve the atomic structure of the protein bound to a phosphate or arsenate molecule down to single hydrogen atoms) revealed how the bacterial import protein selects phosphate. It all comes down to the angle of an unusually short and energetic bond between a certain hydrogen atom in the protein and the bound molecule. This atom is a sort of “phosphate checker”: When the slightly larger arsenate molecule binds, it squeezes up against the protein at some very unfavorable angles. This turns out to be cause for arsenate rejection.

Tawfik and Elias also point out that understanding this clever selection mechanism may have implications for other areas, for instance agriculture, in which the efficient uptake of phosphate is often crucial. All thanks to a scientific storm. Tawfik: “Heated controversy, getting into the fray, is not a bad thing in science. The eminent Max Perutz made this point in his essay I Wish I Had Made You Angry Earlier. If it weren’t for the scientific debate, we might never have stumbled on the question, much less found the answer.”

All is fine with that if you have the right friends, nonsense goes into high IF journals? It is good science that criticism has to go through internet viral mechanisms, here perhaps both times partially because a women researcher was involved and could be exploited to make a political point, all that is fine? What a corruption of science! What about the memristor scandal, where the same happened, namely nonsense going into those super high IF journals:

www.science20.com/alpha_meme/memristor_another_science_scandal-92795

Oh - right - you did not hear about it, precisely because of those "fine" mechanisms. Well played everybody - no wonder the public does no longer trust science!

Actually, you only have to look at this blog or through our website to see excellent science by women. (See the previous 2 out of 3 posts.) Do you think that women should somehow be above the scientific fray?

I think that the main reason the arsenate findings were overhyped is that arsenic has a certain hold on the popular imagination. Had the bacteria been thought to have the ability to metabolize antimony, no one outside the field would have heard been aware of the claim.

Yes, it would have been quite cool if it were true, and there would have been implications for astrobiology, as well, which is apparently why NASA rushed to publicize it.