This is early in the year for Atlantic hurricanes, though we are already up to "D" in named storms. The current mane floating around in the Atlantic is "Dorian" which the National Weather Service is shortly going to rename "Dorian The Zombie." Dorian was a named tropical storm several days ago, disappeared into a system not worth of a name, then re-organized a bit so they are using the name again, and is expected to spit lightly on Florida and then wander off to the Hurricane Graveyard in the mid Atlantic.

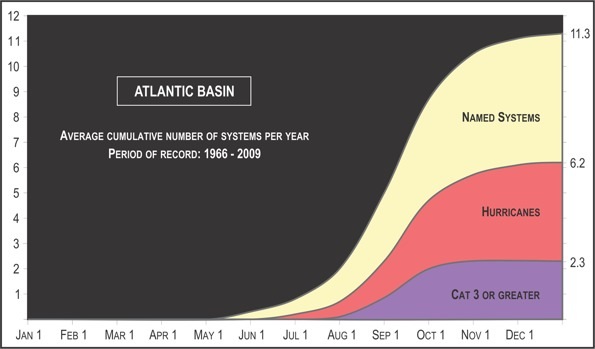

From NOAA: The average cumulative number of Atlantic storm systems per year.

From NOAA: The average cumulative number of Atlantic storm systems per year.

In a typical Atlantic hurricane season, we expect to see about 2 named systems by August 1st, 3 by August 13th, so we are pretty much on track in this year which was predicted months go to be a more active than average year. However some meteorologists expect the next several days or weeks to have fewer hurricanes than normal because of a very interesting phenomenon happening right now: The Atlantic is experiencing a kind of dust storm. Normally, a large amount of dust is blown into the air off the surface of the Sahara this time of year, in waves that happen every few days for a period of time. This dust is blown into the atmosphere and falls down wind at various distances, a good amount of it ending up in the Atlantic Ocean. At present a larger than average amount of dust is being kicked up, and has formed a ginormous plume heading for South and Central America. Here is a modeled simulation of what is happening, from NOAA:

I'm not sure how this is experienced on the ground. I imagine that where this cloud encounters rain storms the rain becomes somewhat gritty and dirty. In the air, a cloud of dust like this can actually affect air travel, though minimally. Patrick Lockerby noted this (a couple of years ago) about Saharan dust and air planes:

Although this dust is abrasive, it is much less of a threat to aviation than the dust from a volcanic eruption. Whereas volcanic dust melts in a jet engine and coats the moving parts, sand needs a higher temperature to melt, and so is merely passed through a jet engine. In the case of piston engines, in the air or on land, desert dust can quickly choke an air filter. The effect can range from the stalling of the engine to the somewhat trivial need to change an air filter more often.

I imagine that people living in areas where a lot of this dust is brought to the ground in rain will mainly notice that everything is slightly dirtier rather than cleaner after the storm, like we experience in temperate regions during pollen season.

The reason I mention the dust is is this: there is the possibility that huge plumes of dust in the atmosphere over the tropical Atlantic will reduce the likelihood of tropical storm formation. There may be

...a correlation between hurricane activity in the Atlantic and thick clouds of dust that periodically rise from the Sahara Desert and blow off Africa’s northwest coast. ... during periods of intense hurricane activity, dust [is] relatively scarce in the atmosphere, while in years when stronger dust storms rose up, fewer hurricanes swept across the Atlantic….

... this makes sense, because dry, dust-ridden layers of air probably help to “dampen” brewing hurricanes, which need heat and moisture to fuel them. [This] could also mean that dust storms have the potential to shift a hurricane’s direction further to the west, which means it would have a higher chance of hitting the United States and Caribbean islands..

John Metcalfe has put this all together in a post on Quartz, which includes some spectacular photographs of floating Saharan dust from various angles.

I would think that a significant dust storm would cool the ocean surface a bit by reflecting energy back into space - fewer Watts hitting the surface means cooler water and less chance of a tropical storm/hurricane developing.

I know, but the timing and scale is different. A few weeks of dust in the lower atmosphere (where this dust is) just makes for some warm dust, with some reflection but not much. Meanwhile SST's are higher than ever and this is not likely to cool them much, if at all. I think the dampening effect is mostly in stuff that happens in the atmosphere.

If, on the other hand, the Sahara starts to do this a lot more that could have a larger effect.

Well I did say "a bit" :) but you're right. It's too transient to have any significant impact on the ocean's surface temperature - for one thing that's a lot of mass to increase/decrease temperatures in and that would take significant time to noticeably affect to any depth

Author F. Mark Granato

Of Winds and Rage

A Story of two storms — One Human, one Weather

75 years ago on September 21, the Great 1938 Hurricane that ambushed the East Coast from Long Island to Maine, remains the worst weather-related disaster in New England recorded weather history. A Category 3 storm, it smashed into Long Island at noon — the only warning, a monstrous tidal wave that ultimately swept most of the New England Coast. The storm moved so fast that one state had no time to warn the next as it advanced through new New england at 70 miles per hour — still the fastest moving hurricane in US history. Nearly 700 people died and damages (in current dollars) were in the billions. By comparison, 2012's "Sandy" was a tropical storm that was discovered and forewarned days in advance. Toss in a a truly terrifying serial killer from the Wethersfield State Prison who chose the wrong time to escape and wealthy vacationers on Napatree Point in Westerly, Rhode Island and you have the makings of a novel that will keep you up nights! Available on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, i-Books and any other e-format as well as in paperback.