tags: researchblogging.org, social behavior, evolution, Psittacosaurus, ornithischian dinosaur

Triceratops are among the most recognizable dinosaurs because of their distinct appearance. They had a large and elaborate bony shield around the back of their head, horns that jut out from the top of their head and nose like spears, and bony knobs on their cheeks. Because these large structures are energetically expensive to grow, they had to serve a purpose and this purpose was likely the establishment of social hierarchies. Thus, these ornaments provide circumstantial evidence that these dinosaurs lived in groups because such structures could have been used in visual displays. But which evolved first, social behavior or elaborate ornamentation?

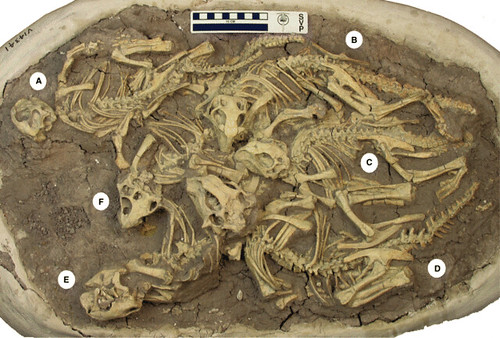

But a recent fossil discovery in the Yixian Formation, an area in northeast China, is helping paleontologists to answer this question. Paul Barrett, a paleontologist at Britain's Natural History Museum, and his colleagues studied a group of young Psittacosaurus that died together after being buried alive by a volcanic mudflow (below);

A herd of juvenile Psittacosaurus from the Lujiatun Beds of the Yixian Formation (lower Aptian: Lower Cretaceous), near Liu Tai village, Yixian, Liaoning Province, China (IVPP 14341). Letters refer to each of the six individuals present. Scale bar represents 100 mm.

Image: [larger view]

Based on their small size (approximately 50 centimeters (1.6 feet) long and weighing about one kilogram (2 lbs)), the six fossilized Psittacosaurus were estimated to be between 1.5 and 3 years old when they died. In comparison, adults of this species were about 2 meters long and weighed up to 30 kilograms.

"We don't know very much about the early behavior of dinosaurs in general," said Barrett. But because Psittacosaurus was an early relative of both Triceratops and Protoceratops, "[t]his discovery shows the early relatives were already social and living in groups."

The fossil discovery consists of six animals of a variety of ages, so it is likely that they came from eggs laid by different parents, observed Barrett. The fossil remains formed a nursery with babies from at least two different parents, he added.

"These animals had left the nest and were already hanging out with each other," Barrett explained. In short, they formed a mixed-age herd, just as modern herbivores do today.

This study indicates that horns and ornate frills only evolved after social behavior developed in these animals. Further, according to an earlier study that was published several years ago, Psittacosaurus cared for their offspring after they hatched [ref]. Thus, taken together, the evidence reveals that complex social behaviors preceded the development of flamboyant cranial ornaments that characterize this group of dinosaurs.

"It used to be thought that social behavior only occurred when these animals had their horns and frills," Barrett concluded. "Now we know that they are incidental to it and that the social behavior comes before them."

This research was published in the recent issue of the journal, Palaeontology.

Sources

"Social behavior and mass mortality in the basal Ceratopsian dinosaur Psittacosaurus (Early Cretaceous, People's Republic of China)" by Zhao Qi, Paul M. Barrett & David A. Eberth. Palaeontology 50 (5), 1023-1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00709.x [free PDF] (images, quotes)

Reuters (quotes)

"Palaeontology: Parental care in an ornithischian dinosaur" by Qingjin Meng, Jinyuan Liu, David J. Varricchio, Timothy Huang and Chunling Gao. Nature 431, 145-146 (9 September 2004) | doi:10.1038/431145a [abstract or free PDF]

Hmmm, I dunno, seems like a lot of conclusion jumping to me, but I guess it's okay for a very preliminary hypothesis. As soon as the university library reopens next month I will take a look at the full articles in the journals. We don't want to state a theory that'll give those creationists a chance to laugh at us, do we. And BTW were those first feathers for flying or for flirting, do you think? The photos that you and PZ use are great! Where do you get all that good stuff?

Why would it be thought that social behaviour came after the horns and frills? I would have assumed the opposite, become social and then show off.

Those horns and shields aren't ornamentation, they're fully functional offensive and defensive weaponry...evidence those animals weren't so much social as anti-social. Compare moose and rhinocerous today...similar "ornamentation", but they're not social even though they care for their young.

Don't think that's really a convincing example, given that Psittacosaurus apparently had long tail bristles. It isn't a frill or horns, but could easily count as ornamentation.

#3 Bob,

Moose and rhinoceruses still interact. On a limited basis, but they still interact. Moose antlers, for example, impress other moose. Moose with smaller antlers tend to be intimidated by moose with larger antlers, and lady moose tend to be impressed by males with large antlers. It's most defintiely primitive behavior, but then we are talking about moose.

Now take an animal that, from the available evidence, was even dumber. Those horns would hurt when they punctured you, but that doesn't stop them from being impressive.

Sometimes a bird sings to attract a female, sometimes a bird sings to warn off other males, and sometimes a bird sings because he feels like singing.

Those horns and shields aren't ornamentation, they're fully functional offensive and defensive weaponry...evidence those animals weren't so much social as anti-social. Compare moose and rhinocerous today...similar "ornamentation", but they're not social even though they care for their young.

As Alan Kellogg suggested, this is incorrect -- actually, in many ways. First, of all the things that today have some sort of elaborate cranial adornment (horns, antlers, etc., in everything from the stereotypical cervids, bovids, rhinos to some lizards, beetles, etc.) do NOT use them as weapons, at least not interspecifically (against other species, usually predators) as most people seem to think. (Kind of sad that the first thing people think of when they see "sharp and pointy" is "that's for stabbing!") If they're used at all in combat, it's intraspecific combat -- against other members of the same species, usually in contests for mates, territory, etc., and in most such contests, the outcome is only occasionally fatal (though it can be, and can be injurious!) -- the ornamentation isn't designed to kill. When not used in combat in any way, though, they function as symbols of strength and intimidation in most instances -- they simply have to look impressive to prevent challenges that lead to combat. This seems to be the primary function of cranial ornamentation; combat, when necessary, is a secondary function; defense, in the few instances when it's used that way, is tertiary. Triceratops may have used its horns in defense against a tyrannosaur, but it was probably a rare occurrence -- the horns and frills were largely display organs, with possible uses also in intraspecific combat. (P.S.: The frills of ceratopsians were comprised largely of very thin bone that would easily have been shattered by a carnivorous dinosaur's teeth -- hardly what you'd want in a defense mechanism!)

Second, the presence of cranial ornamentation is in no way mutually exclusive with social behavior. Look at elk, wildebeest, various other antelope: very social, move in herds, etc., yet still have cranial ornamentation used in display or intraspecific combat. Sure, there are some more solitary taxa, but there are very social ones, too. There's no hard and fast rule.

I didn't say that Triceratops' weaponry was used only for interspecific combat. Species with large horns, antlers, etc. do use them as weapons, primarily against other members of the species and primarily in competition for mates. You can call that social behavior, but I'd call it anti-social. And while some herd animals have small horns, it's my impression that species with the most elaborate headgear tend to be solitary except during rutting, when they meet only to fight and mate. And Triceratops' headgear looks pretty elaborate to me.

When not used in combat in any way, though, they function as symbols of strength and intimidation in most instances -- they simply have to look impressive to prevent challenges that lead to combat.

They only intimidate because of their potential use as weapons. If you rob a bank with a gun, you'll go down for armed robbery even if you don't actually fire it.

Of related interest, here's an interesting article on the horns of dung beetles: http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/291/5508/1505

Turns out that, contrary to Darwin's view, they evolved as weapons, not ornaments.