It is done! The longest-running and most famous camera in the world, Hubble's WFPC2, has been removed and replaced. Scientists will now get to use the Wide-Field Camera 3 (below), and WFPC2 is headed to the Smithsonian.

You've already gotten a chance to taste what WFPC2 has done for our understanding of the Universe, Planets, Galaxies, and Clusters of Galaxies in the first four parts of our series on The Camera that Changed the Universe. What else is left?

Oh, sure, it's pretty and impressive. But that little blob in the middle? That's the Cat's Eye Nebula. The Hubble Space Telescope with WFPC2 took a look at this about 15 years ago, making it the first planetary nebula imaged with the new optics and WFPC2. The results?

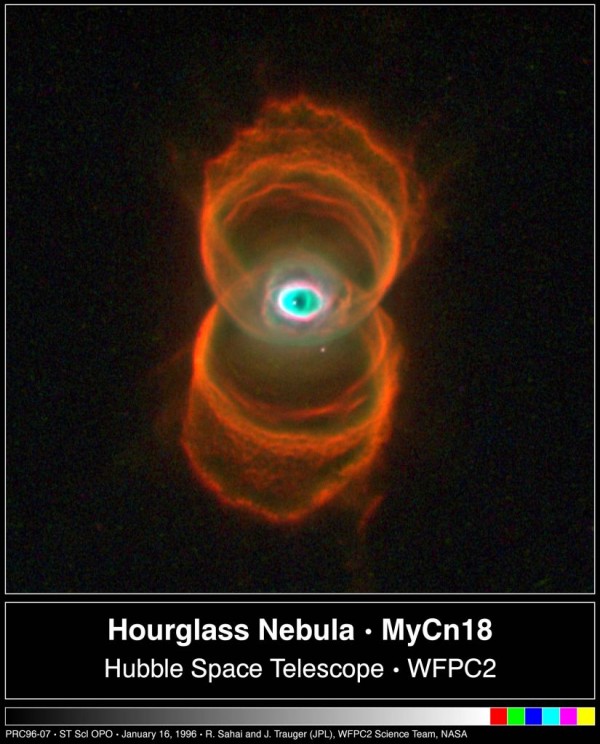

Seriously. Is there anything to say other than holy crap?! But it gets better. You see, these things completely litter the Milky Way. We can do an estimate; there are around 400 billion stars in our galaxy, each star lives roughly 10 billion years, which means about 40 stars die per year. This means that, at any given time, there are about 400,000 planetary nebulae in our galaxy. There are a few spectacular ones that WFPC2 has caught, such as the Hourglass Nebula:

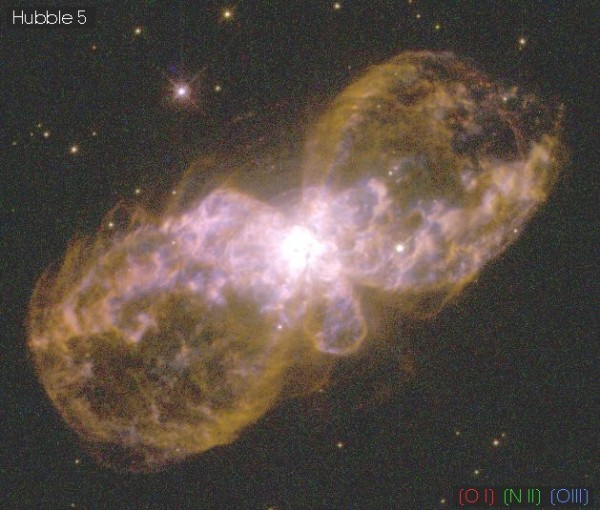

The Hubble 5 nebula:

And the nebula Mz3, known as the "Ant Nebula."

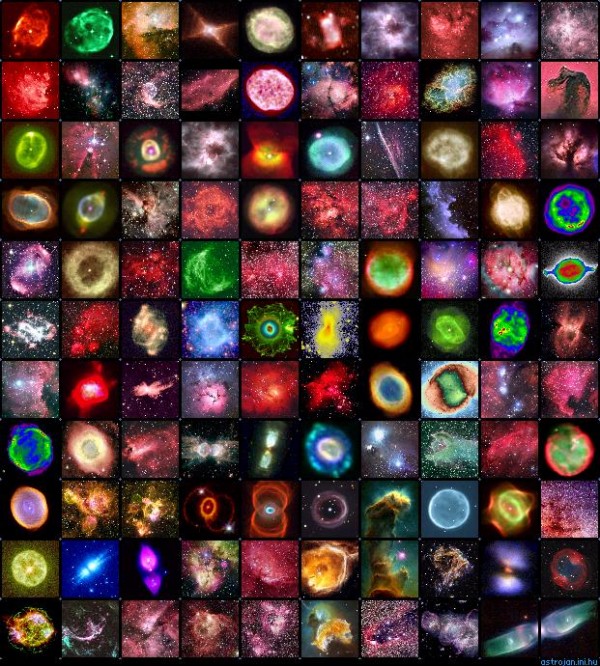

And -- as you'd expect -- we've learned an awful lot about how stars die from these pictures. Surprisingly, only about 20% of stars die spherically. The rest of them make two symmetric lobes and go from there. Here's a sample of many of the planetary nebulae imaged by Hubble:

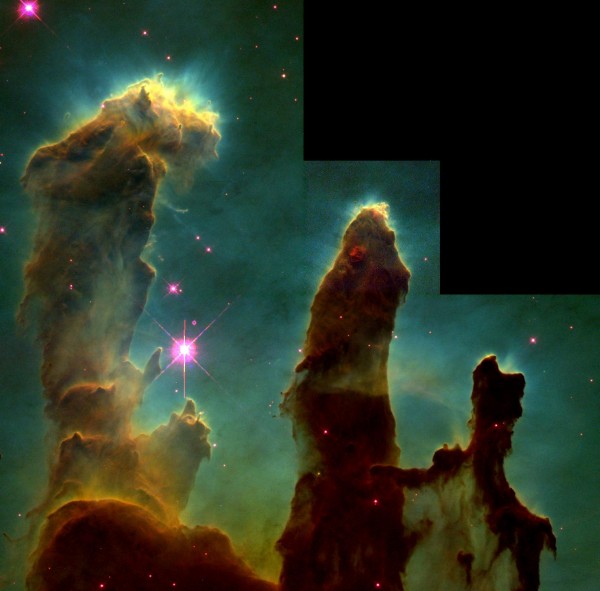

And so this camera has taught us a lot about how stars die. But what it's also told us about is how and where they're born! You see, these nebulae don't just dissipate after a few thousand years; they often spit out entire star systems worth of gas, and trigger the formation of new stars. One of the most spectacular pictures took place deep inside the Eagle Nebula. (This picture, below, is not taken with WFPC2.)

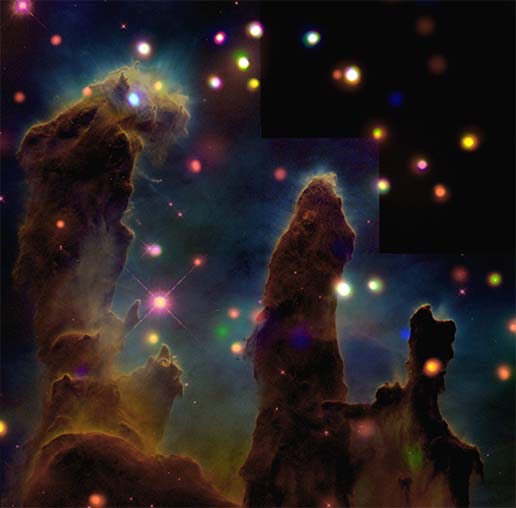

Now, all of those pink stars should tip you off that this is a star-forming region. Where are these stars forming? Where the gas clouds are collapsing to become cool and dense enough to ignite fusion and form new stars. See that structure at the very center of the image? That's what WFPC2 took a look at. Here's what it found (and click to enlarge):

This was so spectacular that they took an X-ray telescope to figure out where the newest stars were forming, and it turns out they are all over these pillars!

And so -- for the last 16 years -- WFPC2 has been teaching us about Planets, Stars, Galaxies, Clusters of Galaxies, and the entire Universe. I bid it a fond farewell, and hope that this look back has helped you to appreciate just how spectacular this telescope and its workhorse camera have been for not just science, but for understanding and appreciating the beautiful world around us.

Saved the best for last. Great series Ethan!

Absolutely amazing. Very well written posts too!

hubblesite.org has some interesting information on how and why the colours are selected and the meaning behind the staircase-looking cropping.

40 stars die in our galaxy every year? So why don't we see 40 supernovas? ...or do we, and I missed something?

Davem,

There are lots of ways for stars to die besides supernovae. Supernovae are -- in fact -- rare. My estimates are that only around 1 in 1,000 stars go supernovae; other people estimate that number to be even lower. Most stars are relatively low in mass; 90% of stars have less mass than our Sun. Yet a star needs to be significantly more massive than our Sun (or in a very special configuration) to produce a supernova. That's why we don't see that many supernovae, only about 1 per century.

One word, WOW.

with our moderate capabilities to understand only part of mystries of the universe we should feel mostly obliged to think about and humbly respect the inteligence behind it.

Wow, amazing. I hope that in my lifetime I can get to actually go into space.

Perhaps in 50 years when I'm old!

Wonderful post. Thanks for this.

Truly incredible piece of technology.

As far as the number of supernova (which are definitely quite rare)...

Even if there were dozens of supernova each earth year, that doesn't mean that the light from them would reach the earth each year. If Rigel (in Orion) supernova'ed yesterday, we wouldn't see it for another 775 years or so. Keep that in mind.

Huble telescope is one of the most important invention in our history. I'm shocked every time I see photos took in our universe. Great series I really enjoy reading it.