"For most of the history of our species we were helpless to understand how nature works. We took every storm, drought, illness and comet personally. We created myths and spirits in an attempt to explain the patterns of nature." -Ann Druyan

Here on Earth, we are well aware of how devastating storms can be. From hurricanes to flash floods, an unpredictable change in weather can turn a serene setting into a catastrophe in no time at all. The clouds that fill the skies can often portend what type of weather is coming, and to me, the most impressive and fearsome of all is the rare and remarkable supercell.

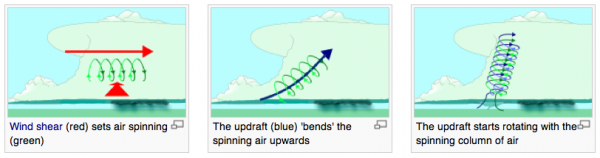

The least common and most severe type of thunderstorm, supercells form when a warm, moist layer of air (typically found above a cold layer, since heat rises) slides below an even higher-elevation cold layer. The wind shear from this motion causes vorticity, or a spinning motion, of the air in the warm layer. As the warm air tries to rise through the cold layer, the rotating vortex becomes vertical, and creates a mesocyclone, which can lead to tornadoes in the most catastrophic of cases.

Even in cases where tornadoes do not form, the supercell storm provides a spectacular deluge and incredible wind speeds.

Image credit: Martin Kucera of http://www.floridalightning.com/.

Under the most extreme circumstances, many tornadoes erupt and the storm -- although usually brief -- can literally destroy an entire town, as was the case a year ago in Joplin, MO. As seen from space, only the flat top of the supercell was visible, blinding us to the destruction that was occurring underneath.

It will come as no surprise that raging storms like this are not unique to Earth. In fact, they are common and can last for extremely long durations on gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn.

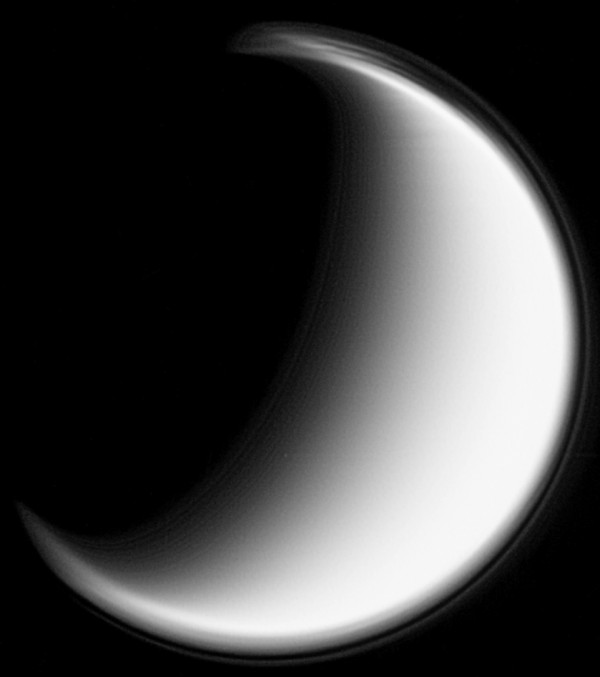

But what may be surprising is that on a relatively small world in our Solar System -- on Saturn's largest moon, Titan -- what appears to be a long-lived supercell storm may, in fact, be raging over its polar region. In the image above, you can see what looks like a cloudy hood over Titan's north pole; this was taken in 2004, when Titan's northern hemisphere was experiencing winter. The atmosphere of Titan extends so high, however -- it's 10 times as thick as Earth's atmosphere -- that sunlight was able to hit the upper atmosphere above the pole, creating that cold-warm-cold layer necessary to produce a giant supercell!

Well, Saturn experienced its equinox back in 2009, and so now we have the onset of winter in the southern hemisphere. And guess what Cassini saw as it flew over Titan's south pole?

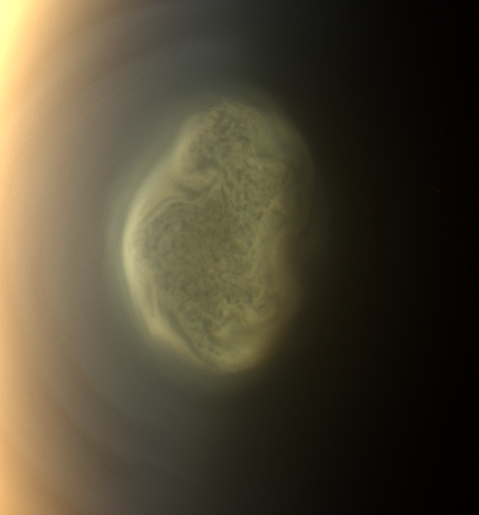

Does this swirling, gaseous formation look like anything you've seen before? Titan's south pole is in the process of forming a vortex that will very likely give rise to a southern polar hood as winter arrives! As the amazing Carolyn Porco states:

We suspect that this maelstrom, clearly forming now over the south pole and spinning more than forty times faster than the moon’s solid body, may be a harbinger of what will ultimately become a south polar hood as autumn there turns to winter. Of course, only time will tell.

Don't believe it? View Cassini's video of the storm yourself!

I can't help but marvel at this storm, rotating at 40 times the speed of Titan itself, and wonder at the titanic catastophes occurring on the world below. With more than 100 miles of atmosphere to see through, we are ill-equipped to find out how this cyclonic polar storm is affecting the terrain below, but I wouldn't be at all surprised if we found out (with the next Saturn mission, nudge-nudge) that there wasn't a torrential methane rain with cyclonic winds reaching down miles upon miles.

Can a storm on a world like this reach the surface? I don't know, but I sure hope we get to find out!

Are those transient white flecks in the last image lighting? (Or just noise?)

Because it looks so much like a cell I was wondering if this couldn't be a gas outburst, or a volcano cloud. You can see something similar halfway this page in the case of the Mount Pinatubo super eruption:

http://www.geolsoc.org.uk/gsl/education/page3042.html

You'd need to find evidence that supports that, chelle, since a storm cell already describes the measured phenomena.

Otherwise, not much point entertaining the notion. It -could- be something else, but no reason to consider it.

Rather like Ethan's take on string theory at the moment.

Isn't it great how we learn about climate by studying *other* planets and moons as well?

@ Dale:

Noise by cosmic radiation et cetera is a common phenomena in images from spacecrafts, affects solid state pixels, memories; plus you have sundry transmission dropouts. If it is black, it is often a damaged pixel in solid state camera I think. If it is white, I would guess CR hit the pixel.

I'm sure they are on the lookout for sprites et cetera discharges.

@Dale

Those specks are almost certainly cosmic rays hitting the sensor. Some of them are even in neat little lines that show the path of the ray as it passes through the sensor array.

"You’d need to find evidence that supports that, chelle, since a storm cell already describes the measured phenomena."

Most likely yes. I had a vortex ring in mind that is often created by volcano's and this 'storm' with its clear edges made me think of that. Storms on our planet seem to have a more dense core, a bit the opposite of this one that seems to be fluffy on the inside.

Although I checked and there are cryovolcano's on Titan:

A cryovolcano (colloquially known as an ice volcano) is a volcano that erupts volatiles such as water, ammonia or methane, instead of molten rock. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cryovolcano

... on Titan:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Titan_(moon)#Cryovolcanism_and_mountains

Anyway that moon seems to be one of the most exciting places in our solar system to go and have a look at, Richard Brandon if you're hearing me ...

Cheers!

Vortex rings don't last long, though..