"Youth is the gift of nature, but age is a work of art." -Stanislaw Jerzy Lec

When stars are born, it normally happens in groups of thousands or more, all at once. They range from just 8% the mass of our Sun, which are dim, red, and long-lived, to dozens or even hundreds of times as massive: the brightest, bluest and shortest-lived stars of all. Because they burn through their fuel the fastest, these most massive stars cease to exist the most quickly.

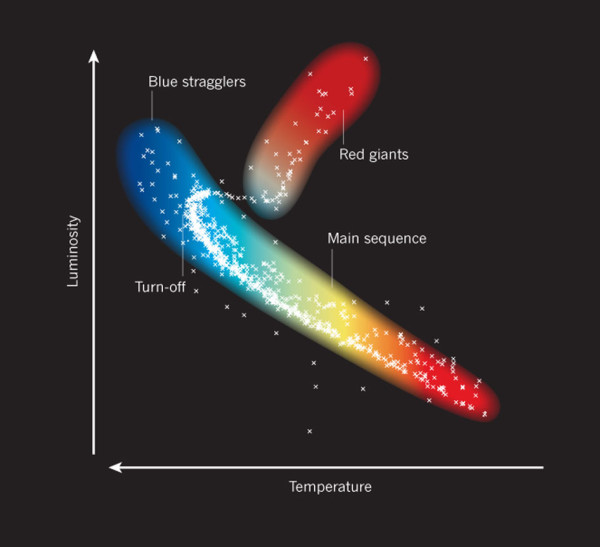

Image credit: Christopher Tout, Nature 478, 331–332 (2011), via http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v478/n7369/full/478331a.html.

Image credit: Christopher Tout, Nature 478, 331–332 (2011), via http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v478/n7369/full/478331a.html.

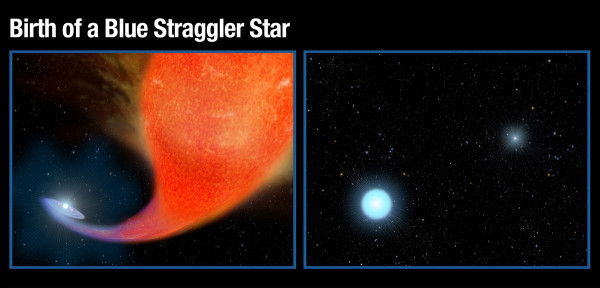

Yet even in the oldest star clusters available for study, stars that are blue and bright still appear! These blue stragglers were once thought to form from the merger of smaller, redder stars, but two recent studies now suggest an alternative: these stars are formed when one star siphons material off of a binary companion, increasing its own mass and creating a dead white dwarf out of its neighbor.

Go get the full story in pictures and no more than 200 words today!

Ethan,

How can you say “Mystery Solved”?

Don’t you mean ‘We have a new theory’?

From your article:

“For a long time, we thought the occasional merger of two low-mass stars gave rise to a heavier, blue star. But there’s *an alternative*.”

“Combined with an earlier study, this *causes a complete rethink* of blue stragglers.”

Within a star cluster, what is the agent which keeps the separation of the individual members from collapsing into a central mass?

@PJ: Angular momentum, basically. The stars in the cluster are all moving around the center of mass of the whole system. Without some mechanism to significantly slow them down, they'll maintain those orbits indefinitely.

You can ask the same question about the solar system. What keeps the planets from all falling into the Sun? And it's the same answer.

Thanks, Michael. Kinda figured that was the answer. Sometimes harder to visualize with many more bodies floating about a common centre.

@PJ: It's the same reason we believe that dark matter haloes remain as large as they are (much larger than a visible galaxy). The net gravity of the system provides an inward bounding force. The essentially random motion of the particles (whether DM particles or stars in a cluster, or even galaxies in a galactic cluster) acts like an outward pressure balancing the inward pull of gravity, but really it's the conservation of angular momentum for each individual particle's orbit. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virial_theorem#Galaxies_and_cosmology_.28…

Systems with strong dissipation, such as smaller clumps of gas and dust clouds, can lose energy as a result of collisions, radiation, etc., and collapse gravitationally.

Thanks, again, Michael. The math is going to consume some time to get through. It is more than 50 years since I studied at that level. As they say, ' if you don't use it , .........' But, I do get the gist of it. I guess the sheer scale of the parts of our universe become overwhelming.

:)

PJ, the collapse isn't even, and there are places where the density is higher and these will grow too, until they become stars, and the gas between them will be "fought over" by their respective gravitational forces and collapse to one centre or the other.

So you won't get a complete collapse into one centre, just a bigger or smaller star depending on how big the original deviation from even density it was, and how quickly it formed to grab the gas.

It's the same thing with an accretion disk there, except that when the star turns on, the photon pressure blows away much of the gas more strongly than the other centres of density can grab onto it, and these become planets.

And remember that any mass evenly distributed outside the centre of gravity from the position in question has no net effect, so dark matter halos do not change the gravitational activities of collapsing matter closer in on the galactic plane.

To me it seems that deeper insights into this relay on the question whether the universe has any kind of logically (mathematically) closed shape. Whether it is embedded in something 'bigger' than itself with clear boundary conditions.

Another question: Has there ever a mystery been solved? If you solve one, you solve all. That's what I tend to think about reason.

Would you please don't blame me if my thought does not meet the demands of this board? I'm just interested and do not speak that decent english.

"Another question"

You hadn't asked one yet.

"Has there ever a mystery been solved?"

Yes.

"If you solve one, you solve all."

No you don't. You solve one.

" That’s what I tend to think about reason."

That is another mystery. Why do you think that? And if you answer it, will the solving of that mystery solve every other mystery?

You are right, I had not asked a question before I asked the other one.

"Why do you think that?"

To me the word 'mystery' semantically appears as apparent but apparently inaccessible. If you solve it, it hasn't been a mystery at all - you just have not had the data as yet to see something obvious.

"... will the solving of that mystery solve every other mystery?"

The true mystery remains mysterious, so, yes, solving a mystery solves the question how to solve a mystery and therefore all other mysteries at once.

"To me the word ‘mystery’ semantically appears as apparent but apparently inaccessible."

Then this is not a problem with the mystery and is a problem with what you've dumped onto the word. Solve that problem first and learn your words.

"solving a mystery solves the question how to solve a mystery and therefore all other mysteries at once."

But if the mystery we had was "why do you think that", either you have answered it and your claim above is wrong, or you haven't answered it and we still have had no answer to that, and we are still pending on it.

Please rethink the words you are using because they don't appear to mean what you want them to mean, and including the word "mystery" a score of times doesn't make it any more mysterious than it does to "The Mystery Machine".

"If you solve it, it hasn’t been a mystery at all"

WRONG.

10 billion percent WRONG.

It's not a mystery any more.

What's in the box? It's a mystery. Open the box: no longer a mystery.

What causes thunder? It's a mystery. Develop the scientific method and answer it with "The collapse of superheated air caused by the passage of a massive charge through the atmosphere, whose passage causes the lightning strike and the thunder is the aftermath. No longer a mystery.

If you're going to claim that anything that can be solved NEVER WAS a mystery, because eventually, in the long passage of time, the mystery *will* be solved, then you're working from your own dictionary and thesaurus, and you should get with the language of the rest of the hominids here.

Or give up pretending to converse.

"What’s in the box? It’s a mystery. Open the box: no longer a mystery."

I don't think so. Your setup was not about a mystery, it was just an open question.

When you open a box you expect to see at least something. If you would see literally nothing comprehensible after having opened the box, that indeed would be mysterious.

"I don’t think so."

OK, so why should anyone else participate in your personal delusion?

If you're going to define a mystery as something that hasn't been solved, then your question about whether any mystery has ever meaen solved is meaningless.

And if you wish to ask meaningless questions, either piss off or plop that steamer here:

http://scienceblogs.com/startswithabang/2012/09/23/weekend-diversion-yo…

Have a nice day.

For some reason, the letters b e e and n eluded my fingers. But who gives a crap.

@wow

self-indulgent little creature aren’t you

disgusting

proof:

http://scienceblogs.com/startswithabang/2015/12/17/what-are-quantum-gra…

Oh, gosh, how unpleasant the Forbes experience is. I am a very-long-time, always-appreciative reader of SWaB, but Forbes has killed the pleasure for me. So long Ethan et al., and thanks for all the fish.

It's probably worth telling Forbes too. After all, they want people to visit, and if all they get is people saying their actions are fine and everyone else just leaves in disgust, they have nothing to point them in the correct direction.

@wow

boring little creature aren't you

directionless

http://scienceblogs.com/startswithabang/2015/12/17/what-are-quantum-gra…

I'm not the one spamming the hate filled bile with zero content, shithead.

hateful little monster aren't you

windbag

http://scienceblogs.com/startswithabang/2015/12/17/what-are-quantum-gra…