“Even though the future seems far away, it is actually beginning right now.” -Mattie Stepanek

After another tremendous week here at Starts With A Bang, including one where I recorded a new podcast (look for it later this week on SoundCloud), it's time to take a look back and review all that we've been through. From last Saturday through the past Friday, here's what we saw:

- Are there different types of time and space? (for Ask Ethan),

- Deepest view of the Orion nebula reveals shocking discoveries (for Mostly Mute Monday),

- Forty years ago, we landed on Mars... and found life?,

- Apollo 11's landing was 47 years ago today,

- Dark matter may be completely invisible, concludes world's most sensitive search, and

- The most impossible technology from Star Trek.

There are some great new pieces coming up this week, but before tomorrow kicks them off, let's hit the best of what you had to say on this edition of our comments of the week!

Image credit: David Champion, of an illustration of how many pulsars monitored in a timing array could detect a gravitational wave signal as spacetime is perturbed by the waves.

Image credit: David Champion, of an illustration of how many pulsars monitored in a timing array could detect a gravitational wave signal as spacetime is perturbed by the waves.

From Wow on the death of Steve Detweiler: "Arhythmia can set in no matter what your fitness level. Lack of fitness only gives other reasons for heart failure."

As far as I knew, Steve was never a steroid user and wasn't overdeveloped, just a healthy older man who did a lot of running and engaged in other athletic endeavors all throughout his life. His "claim to fame" athletically is that he wrestled (and pinned!) a much larger and more famous wrestler when he was in high school: someone named "Rick Fliehr," who American audiences might know better as Ric Flair. They went to high school together; Steve was two years older and about 30-40 pounds lighter.

Steve's legacy work, other than the Chodos-Detweiler paper, will likely be on using pulsar timing to detect very long-period gravitational waves. As Dave Reitze recounted:

"[Steve] theorized that you could detect gravitational waves from pulsar timing using radio astronomy. You’d have to look not for days or weeks but years, and even 5-10 years. If you had enough pulsars located over points in the sky, you should be able to look at a difference in timing from those pulsars. From that difference in timing, you could infer the existence of a gravitational wave background at extremely low frequency gravitational waves: in the nanoHertz range. This is an experiment going on right now. There are a number of these experiments working together, the NANOGrav collaboration in the United States, one in Europe called the European Pulsar Timing Array and one in Australia called the Parkes Pulsar Timing Array, and they all share data and work together. They are potentially on the verge of making a discovery of these low-frequency waves using a method that was first proposed by Steve Detweiler, so in some sense I think Steve was a real pioneer there."

Good stuff from a good man and a great colleague. He'll be missed by all who knew him.

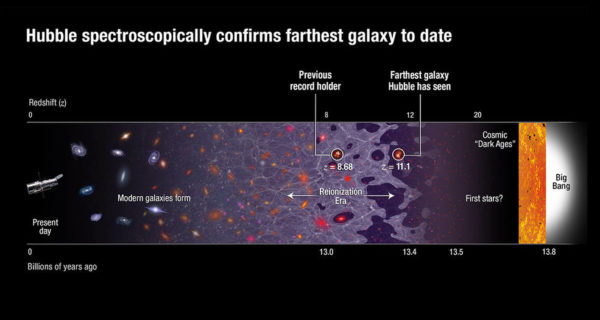

Hubble spectroscopically confirms farthest galaxy to date, at a redshift of 11.1. Image credits: NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI).

Hubble spectroscopically confirms farthest galaxy to date, at a redshift of 11.1. Image credits: NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI).

From MobiusKlein on the expanding Universe: "But is the universe expanding for impractical purposes?"

What do you mean by "practical" when you consider this question? Do you mean things that originated on and that we interact with here on Earth? For those purposes, we cannot tell that the Universe is expanding. But you might as well say, then, when you walk around in your own backyard (or around your city block, if you live in a city), "the Earth is flat for all practical purposes."

And you'd be right, in a very specific, very ignorant sense. You're saying, in effect, "I'm not looking at enough information to make a data-driven decision, and therefore I can conclude whatever I want based on what I looked at." So if you look at the light from galaxies other than our own, particularly if you start looking beyond our local group, you discover the expanding Universe, just as if you look at a large enough section of the Earth, you discover its curvature. So it depends on what you mean by practical.

From Chris Mannering on dwarf galaxy dark matter: "I’m trying to track down a comment I made in response to your idea for an explanation of why dwarf galaxies have higher dark-matter, namely that dwarf galaxies had more baryonic matter in the past but loses it from the galaxy at a faster rate then DM."

Chris, did you mean this post here, where you commented "I don’t think this works because the corollaries are

– all small galaxies below some threshold, T, have the same dark matter mass, DMr, as one another respectively

– DMr = 5/4*T (assuming 4 parts DM to 1 part baryonic mass the dominant ratio above threshold T)", and then "the second corollary should have been T = 5/4DMr"? That's all I can find, but you may have been posting under one of the other names you sometimes post under, like Lucy Hibbs?

Oh yeah, I forgot to tell you all, when you sockpuppet, I notice. Bad form.

In any case, this is not my own personal theory, but a well accepted consequence of having galaxies of various masses (and various gravitational potentials) that then form stars and generate stellar winds and outward fluxes of particular magnitudes. When the velocity of the matter exceeds the escape velocity, good bye baryons!

An infrared view of the brightest part of the Orion Nebula. Image credit: ESO/H. Drass et al., color-corrected by E. Siegel.

An infrared view of the brightest part of the Orion Nebula. Image credit: ESO/H. Drass et al., color-corrected by E. Siegel.

From PJ on the infrared Orion Nebula: "Love the Trapezium photo. E & F stand out well, and it looks as if there are a few more cousins in that local group. Brilliant!"

It's pretty interesting, because it was called "trapezium" because of the four bright members that make a trapezoid shape. Apparently -- quite apparently -- there are many more than four in there.

The brightest regions house not only the most massive, brightest stars, but many other, fainter objects abound throughout the nebula. Image credit: ESO/H. Drass et al.

The brightest regions house not only the most massive, brightest stars, but many other, fainter objects abound throughout the nebula. Image credit: ESO/H. Drass et al.

From Sinisa Lazarek on the discovery of more sub-stellar masses than we had previously thought: "Does this mean that the rough estimate of MACHOS present in the galaxy is about 10 times off? Thus we need less “exotics” DM?"

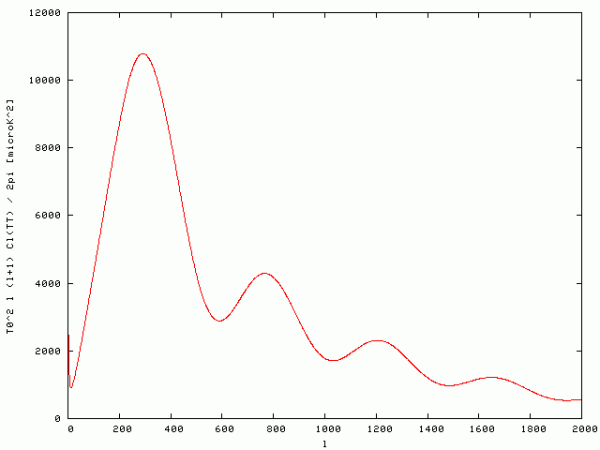

This question comes up every time someone finds more matter out there that hasn't formed stars. The question is, "ooh, could this be some of the dark matter, and therefore could we need less dark matter than we thought, or maybe even none at all?" And the answer is always the same: NO. The reason it's "no" is because we know the total amount of mass present in the Universe from a slew of observations: clustering, lensing, baryon acoustic oscillations, fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background and more. We get the same number from all of these observations: about 30%, plus or minus about 3%, of the total energy in the Universe is in the form of matter. Normal and dark matter combined. And we know, from again a slew of observations, including the CMB, the large-scale structure of the Universe and Big Bang Nucleosynthesis, that the total amount of normal matter in the Universe is around 5% of the total energy, plus or minus about 0.5%.

What the Cosmic Microwave Background's fluctuations would look like with no dark matter: woefully mismatched with what we see. Image credit: E. Siegel, generated with CMBfast.

What the Cosmic Microwave Background's fluctuations would look like with no dark matter: woefully mismatched with what we see. Image credit: E. Siegel, generated with CMBfast.

Now, there might be slightly more brown dwarfs and slightly less plasma; there might be slightly more planets and slightly less gas; there might be slightly more black holes and slightly less dust, etc. But the total amount of matter is well-known, and adding a little bit more of one type doesn't change the total amount of dark matter at all.

From Denier on finding life on Mars: "Are you thinking it could be that long before we know because the next set of exobiology instruments being sent to Mars in the next few years (ExoMars Rover) are in the hands of the Russians and ESA?"

If ExoMars works, lands successfully and operates properly, it could find signs of past or present life on Mars. It would be amazing! But it's really quite a limited piece of equipment, as is Mars Rover 2020 from NASA, which could figure out whether the methane vents on Mars are organic in nature or not. But these aren't really capable of looking for life so much as organic molecules and biosignatures, which often have multiple confounding possible explanations.

In other words, they can provide "hints" of life, or under very rare circumstances, strong evidence for life. But they cannot say, "this is an organism of Martian origin and it is or was alive." That technology is not aboard either rover. Which, honestly, is kind of a shame. That's why I think it may take that long.

Image credit: NASA / ESA, via http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Human_Spaceflight/Historic_handshake_….

From Wow, arguing with Denier (and others) about the humans vs. robots argument in space: "Or fix the errors with nanobots, increase our DNA so that where cold blooded creatures use DNA information to code for development paths in different weathers (we mammals have temperature control and therefore jettisoned much of our genetic information as no longer necessary), add DNA to form proteins and other signals to repair damage to our cells from radiation."

Yes, we can (and should!) send robots and other uncrewed missions to the outer worlds, into the hostile environment of space. We can learn so much, get a tremendous "bang for our buck," put no human lives at risk, and build a robot much more hardy than a meatbag like us human beings.

But also... I want people to care about space. I want them to care about space exploration, about investing in this frontier, about dreaming of a better life for humanity on this world and beyond. And I don't see us getting there. So when people say "human spaceflight," I say yes. And when they say, "robotic missions," I say yes. Yes to it all, and yes to a greater investment, a better future, and an interplanetary human civilization!

(Boy, election season is getting to me!)

A diagram of the LUX detector. Image credit: LUX Collaboration, diagram by David Taylor, James White and Carlos Faham.

From Elle H.C. on the LUX experiment: "What’s the difference with this one, and the one to detect proton decay, such as the kamiokande?"

If you want to watch for proton decay, you get a bunch of free protons together and look for decays that have energies of less than the mass of a single proton. You look for decay products like positrons and pions. And so you need individual protons, or hydrogen nuclei.

If you want to watch for a dark matter collision, you're looking for a nuclear recoil, which means a massive particle colliding with a large-cross-sectional atomic nucleus that won't interact any other way. Proton decay ain't gonna happen in a large, bound-together nucleus, so the LUX experiment isn't sensitive to that. That's the biggest difference: recoil vs. decay. But other differences are that the WIMPs that LUX is looking for are in the ~10 GeV-3000 GeV range, while the proton decays are < 938 MeV. Different energies. But they both require big arrays of photomultiplier tubes and a big tank full of matter, so they have some similarities, too.

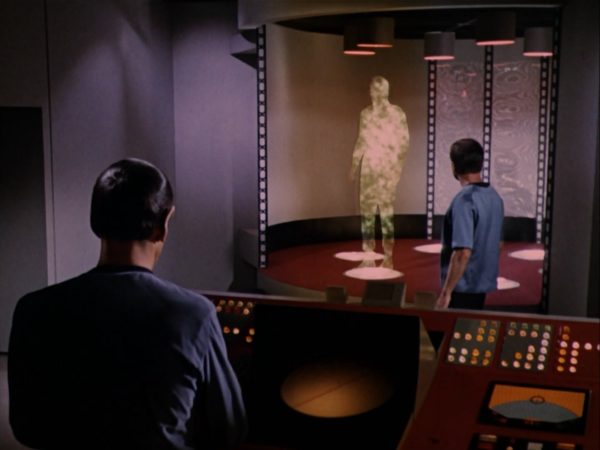

Three members of the Star Trek crew beaming down off the ship. Image credit: CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images.

From Michael Shuster on the transporter: "Michio Kaku’s “Physics Of The Impossible” covers the transporter and some other familiar themes, and is a great read overall. BTW I believe he said that the transporter was a device of production convenience because of limited budget."

I have nothing bad to say about the book, which you can check out at Amazon here. But that fact is not a case of "Kaku says" but rather a case of Gene Roddenberry himself (along with Stephen Whitfield) writing it in their book, "The Making Of Star Trek." According to that book, Roddenberry originally wanted to have the crew depart the Enterprise via shuttlecraft and land on each world they wanted to visit. But this was unaffordable, and so the transporter was devised. Being made before computer animation, incidentally, a solution of glitter and water was agitated and filmed, allowing the "fade out/fade in" effect of transporters, and explaining why different colors were used for different civilizations' technologies.

And finally, from Carl on a feasible (?) plan for a transporter: "I can readily envision development of teleporter technology. First, remote 3-D printing. Second, a baseline model for human tissue. Third, an architecture of a human (common nerve connections, hormone levels, etc).

Now we can print a human somewhere.

Next, we need to measure the important pieces of the teleporter subject. Brain connections, muscle mass, hormone levels.

Modify the base “human model” to match the measurements and remotely print someone who looks like and has the same memories as the teleporter subject.

Lastly (or maybe as part of the “measurement phase”), destroy the original.

Seems very likely to work IMO."

Sure... except that's not transporting you, that's copying you, killing you, and trying to bring your clone to life. And if you could do it, it just might work! Rather than a Heisenberg compensator, you could set up a quantum computer with approximately 10^27-10^28 bits: the number of particles in your body. Right now, we're up to 10^3 qubits. So just 24 more orders of magnitude to go! Who's a fan of Moore's law? Anyone?

Thanks for a great week, everyone, and I'll see you back here tomorrow for more wonders and joys of the Universe!

@Ethan

thanx for addressing the question, just I feel that you answered a different question. I know that the TOTAL ratios in the UNIVERSE are not going to change much because of the restrictions and different measurements that you listed. My question was just about the galaxy.. or even more precisely about our own galaxy. Because the observation showed ten times more dwarfs then before. Maybe I'm nitpicking, but IMO "ten times more" is not "slightly more". This of course doesn't influence the DM halo AROUND the galaxy (where most of DM is). But I expected that 10x more machos would influence the mass content of our galaxy more than slightly.

<Janis attr="love light">Come on, man, get it together.</Janis>

Every night, the pattern of electrical activity that is the conscious "me" disappears. It doesn't go underground somewhere in my brain or go into some standby/dormant mode, this pattern ceases to exist. Not there. Gone. Noneexistent. New patterns, associated with sleep and dreaming, take its place. Then when I wake up, my brain recreates the pattern that is "me" from stored information...probably not exactly the same as it was before, I just don't notice the differences.

The same thing is true for my physical structures, though on a much slower timescale; over time, the structure that is currently "me" will get replaced by (previously) foreign atoms.

The idea that our consciousness or self is continuous is something of a myth or psychological crutch; we are, technically, neither continuous in physical makeup nor in terms of the electrical patterns that make up our conscious selves. Destroying an old pattern and then later creating a duplicate via stored bits and bytes (what Ethan objects to) is a lot more similar to what your brain does every night than one might expect.

So I, for one, would be pretty happy jumping into a transporter, even if I knew it meant that the only thing being "transported" was information and that what was created on the other end contained none of the atoms that made up the "me" on the transmitting end.

@Ethan

From your July 2016 Forbes article:

With a sensitivity range that sets the record from just about a fifth of a proton’s mass (~0.2 GeV/c2) to about ten times the mass of the heaviest known particle, the top quark (more than 1,000 GeV/c2), LUX has pushed the interaction limits not only lower than ever before, but significantly lower than the experiment was even designed to push them.

So have DM particles yet managed to achieve a level of such extreme puniness that it would make DM, as envisaged post LUX, an extremely unlikely candidate to be one capable of pushing around Andromeda sized galaxies so to ensure a uniform rotational speeds across their width, as if DM particles in galactic haloes formed gangs of some kind of super powerful schoolyard bullies?

The recent LUX results strongly suggest that the existing scientific paradigm involving DM and the G Force, whatever its cause, has failed utterly.

So, how likely is it that the existing paradigm will ever be reviewed, from the ground up, and be replaced by an alternative paradigm, one that is capable of explaining all existing anomalies and be capable of getting through the existing peer review barrier?

Rhetorical question, I know. The answers to my final question are: slim and none.

In general, alternative ideas must be proposed and tested (and do better in tests than the current models) before paradigm review and replacement happens.

You also somewhat imply that science isn't looking into alternative ideas, that it is monolithic and unanimous in its support for DM. This is not true; Ethan has covered the alternatives being proposed and tested by scientists before (such as MOND). He obviously doesn't think they are as good, but the point here is you are wrong in implying that science is not looking at alternatives; continued work on ideas like MOND functions as "review of the current paradigm" per your request. If the current paradigm hasn't been replaced, its because all the alternatives being investigated are (AIUI) worse at explaining things than the current idea - its not because no such alternatives have been considered by science.

@eric

I was not in any manner, shape, or form challenging the existence of DM or, for that matter, suggesting any modicum of support for MOND.

I originally had a brief paragraph in my original draft post that covered this aspect, but I said to myself: "Nah, no one would ever assume that I believe in that stuff," so I deleted it.

I was wrong to do so.

My mistake.

"As far as I knew, Steve was never a steroid user and wasn’t overdeveloped, just a healthy older man who did a lot of running and engaged in other athletic endeavors all throughout his life. "

Although the bit you quoted from me didn't contain any such reference. The bit you DID quote merely states that arrythmia can exist in a healthy body with no physical problems other than the chaos in signalling for the heartbeat.

And for professional athletes, performance enhancing drugs are a killer, because building the muscles artificially will build the heart muscle, a damn good reason to police drug use in all sports, even if you take the libertarian stance of "As long as every competitor gets the advantage too, it's their body, so why interfere?". It was a possible reason, and if so, an object lesson to anyone thinking to gain an edge by skirting the rules and looking for a chemical solution to the hard work of training.

Hell, up until the 90s, it wasn't conceived that steroids would cause heart attacks in bodybuilders. Where is the censure of someone who took them decades ago and stopped as soon as they found issues with it? Nowhere. But the damage is done.

Alan L:

Okay so then I'm curious: what part of the 'current paradigm' do you think is so badly out of whack that it needs to be rethought from the bottom up? Because your #4 takes pretty strong aim at 'DM and G.'

And what alternative idea(s) (in the theory area you're concerned we're getting wrong) do you think science should be working on?

"So when people say “human spaceflight,” I say yes. And when they say, “robotic missions,” I say yes. Yes to it all, and yes to a greater investment, a better future, and an interplanetary human civilization!"

I say that we need a cheaper method for doing spaceflight before making much of human exploration, though. If we don't wait, we must go for colonisation, not exploration, IMO.

Send enough people that they can survive there and do months or years of work before having (if ever) to leave. Build bases that outlast a single mission, bases where we can have humans live.

Going out a handful at a time for a limited sortie plays a half-assed game, and one that doesn't play to the strengths of a full intelligence: changing the parameters in complexity with the mission. We can't program an AI with enough to deal with a year long survey, we don't have to program a human, only give them the tools to survive.

I would end with this: we can build those nanobots to fix errors in our own cells, keeping us alive in a hazard of interstellar space. Evolution got a system that is amazing in its complexity, but that complexity is mostly serendipity. We can design a plethora of systems each designed specifically to do one thing, and being designed, will be much more efficient at that one job.

We don't have to rely on heat shock proteins to keep our cells alive, when they can be co-opted for a different use by a biological emergency: we can make a bot to do the emergency repairs and leave the HSP to keep its normally occupied role intact.

"It’s pretty interesting, because it was called “trapezium” because of the four bright members that make a trapezoid shape. Apparently — quite apparently — there are many more than four in there."

Though you need decent optics and a good magnification to make out the fifth bright one, otherwise it's rather hard to see it as another star. Nowadays, a good 4-5" scope at 150-ish magnification can make it pretty easy to spot that it's not a trapezium, a poor geometry 3" or less scope is harder to separate them out at any magnification.

"The idea that our consciousness or self is continuous is something of a myth or psychological crutch"

Not really. It's ontology. That which we perceive as us we call consciousness.

Transporting you via cloning at a distance isn't really transporting. Did you see the movie "The Prestige"? Was Hugh transporting himself or cloning?

I think the problem of answering the question you point out, eric, is we don't know why consciousness. We don't know what we HAVE to get right to keep your consciousness going in a transporter.

The reason why Scotty didn't take the transporter was exactly because of this issue (according to ST cannon).

My point is that nature doesn't "keep your consciousness going" in your regular body on a fully continuous basis. So why require a transporter to keep your consciousness going during transport? As long as the pattern that appears at the other end is an accurate reconstitution of the pattern that appeared before transport, that's basically the same as falling asleep (pattern disassembled/disappears) and waking up (pattern reconstituted from information held in hardware).

I should say that from an engineering perspective, there may be good reasons to 'keep the pattern going.' I.e., it might introduce less error to just sustain some pattern of activity rather than store the important information about it in some hardware state, and use that info later to rebuild it. But from a philosophical perspective, a transporter that uses the latter process should not unduly disturb us since that is the process our brains already do.

"My point is that nature doesn’t “keep your consciousness going” in your regular body on a fully continuous basis. "

Mine is that you can't make that claim unless you know what your consciousness is. The problem with transporter tech is that we have to know what that means before we transport the first human, too. Otherwise we are risking inhumane slaughter and cloning.

When we HAVE worked it out (or ignored trying and done it anyway), we can make a stab at answering whether it's possible or not. Until then, it's not a question it's possible to answer without begging a huge swathe of questions.

And to me that spells it as morally impossible to do.

Wow, unless you're a dualist then ultimately you have to accept that some future conformation of different atoms will be you just as validly as your current conformation of atoms is 'you' today, even if carbon atom 1' is substituted for carbon atom 1, carbon atom 2' is substituted for carbon atom 2, etc...

You're making the point that we don't yet know which conformations of atoms are critical to you-ness and which aren't. That's true. But it doesn't change the fact that if I can substitute atoms with sufficient accuracy, it won't be any different than what your body and brain does normally over time. A transporter would do in one fell swoop what nature and your body does progressively over years or decades, but the timing is really the only difference.

Ah, the ethics of doing it when you don't know how accurate you need to be is a different question. Yes sure, I would agree its unethical to do as long as the accuracy is poor or you don't know whether you've reached 'sufficient accuracy' because you don't know what sufficient accuracy is. But (a) most scientists would agree with you, and (b) that's not a new issue; bioethics has already tackled it and resolved it, because of cloning. The scientific consensus conclusion after we figured out how to clone animals was basically exactly what you're suggesting - i.e., we shouldn't copy humans until we are highly confident we won't introduce an excessive amount of genetic or developmental errors into the copy. I'd expect that to be true here too.

Developing a method to copy someone is loaded with interesting bits. I expect that first, we'll create an AI. It will be in a computer (most likely) and not a copy of anyone but instead, an accurate-enough model of neuron connections to be self-aware.

Can you turn that computer off without murdering someone? What does it mean when you copy the program? There are equivalences to teleporting (copy & delete original), mature cloning (now there are two), and resurrection (restore after deleting original).

I doubt we'll let ethical considerations get in the way of trying everything & anything. Or maybe I should say that in the Bell-curve of experimenters' ethics, there is lots of room at one end for some people to be just fine with ... whatever.

How long could a body last being scanned & reduced bit by bit at one end, transmitted at C, then reconstituted at the target site? Over what maximum distance would a failure occur?

:)

@ Wow & Eric

interesting discussion on copy/clone. I think that from bio-engineering standpoint.. ultimately you CAN'T have 100% clone in terms of both physical and mental aspects.

There are several issues to address here, and mental traits are more important IMO since physical clones are more or less present in nature altough not truly identical clones (twins, cloned sheep etc).

As Wow pointed, we don't really understand what conciousness is, so how would we decide if this copy of "mental" is same as original. I don't know what I'm going to do or think tomorrow, how can I then validate if a clone of me is actually a 100% me or my evil twin instead?

The other one is our enviroment which shapes us both mentally and phisicaly. If both copies exist at the same time, they will evolve into different people simply by virtue of different interactions with the world. If only one instance of clone is present (as in ST transporter) then noone is the wiser since old is destroyed and only one person comes out.

Further, think about inevitable randomness present in a system as large (not size wise, but information and particle wise) as us. Even if you succeed in replicating the physical body 100%, the second it starts to "work" it will work differently then the original.. cells mutate, an electron tunnels, things happen.. etc..

So IMO, ultimately depending on the tech used, you will either create a super monozygotic twin that will then go on to live his/her life as they see fit and have a a personality distinct from your own. Or you will kill yourself, and put forth a clone that will again go on to live his/her life, but no one could say if old you would do things differently. So in essence, it IS a new person making decisions for him/herself and what you today think as you, is gone in the act of cloning.

p.s.

a simplified scenario to consider... simple automaton "bug" robots. You create 2 identical small robots.. same parts, same code, same libraries. A true clone in canonical sense. And equip them with just basic "instincts" like: move away from walls, seek light to charge panels, avoid obstacles and such. And you release them in a room. After a day, those two same robots would have covered different distances, be found in different parts of the room, their memory would contain different information and their "experiences" would be different. And that difference would only grow with time.

That "feedback" between what you see and what you do, is what creates chaos and I think ensures that even if parts and rules are the same, you end up with emergent notion of "self" which is unique to you.

Sinisia:

I agree, but this gets back to an earlier comment of mine about the myth/psychological crutch of thinking we are continuous in a way we are not. The you that woke up this morning was not a "100% clone" of the you that went to sleep the night before. Some of your atoms are different. Some of your neural connections are different. Some of your thought patterns are therefore different. You don't notice the difference, but its there nevertheless. So if transporting creates the same differences as, say, an hour of sleep, why get all existentially angsty over it? That transported you is just as much you as today's you is yesterday's you.

@ Eric

" ... an earlier comment of mine about the myth/psychological crutch of thinking we are continuous in a way we are not."

That is true. We (as constituent parts) are not continuous. Our perception of ourselves is however IMO. Thus we think of ourselves... our ego if you will, as continuous.

I think @eric is right on this, but his eagerness to jump into the clone and kill machine is seriously cold blooded. The person who arrives is the person who was sent but I don't even like getting my blood drawn. I'll let @eric do it and tell me how it was.

Well lol I'm not going to push anyone else in, if that's what you're worried about. And I give blood on a very regular basis. :)

Summing up some thoughts on the is-it-death-or-relocation, it seems to me that there are two differences between what a transporter does and what nature does every day, and its these two differences that intuitively bother us. The first is rate of change: 'natural' replacement of atoms is pounds per day, a transporter is hundreds of pounds per (milli? micro?)second. While qualitatively they're both replacing atoms (though ironically, a perfect transporter would change your brain-state less than experiencing the transport time), our human intuition seems to want to draw a hard distinction between what the rates mean for selfhood. The second difference is the possibility of copy; our normal experience of cellular and brain-state change over time doesn't create extra versions of us, whereas a transporter theoretically can.

The thought of multiple copies brings up difficult questions about selfhood (which one is us? All? None? Just one? If we base the decision on atoms conserved, then isn't natural development just a form of slow-copying, and the "original me" can be said to have died years ago? Funny, I don't feel like a copy of a long-dead former eric)

I expect that we'll never reach philosophical or scientific consensus on these issues...mostly because, like Trek vs. Wars or angels dancing on a pinhead, the problem is not one we'll ever actually experience. Transporters can't and won't be invented. Thus it will never be really socially important to resolve it.

"Wow, unless you’re a dualist then ultimately you have to accept that some future conformation of different atoms will be you "

Not in actual fact.

Look again at Conway's Game of Life simulation. WE DO NOT KNOW if a slightly different starting grid will create a different pattern.

The pattern, like "consciousness" is emergent, and we really don't have an idea what would be necessary to make "you". Whether there's a "you" in a cartesian sense (and I am not), or just a "you" in a "the one making the decisions in your future existence" (As SL points out: if it made different decisions than the undeconstructed you, is that proof it's not actually you? And how much of that change would have occurred merely by the presence of "another you"?) is irrelevant, because as long as we ascribe a "you" to a living entity, it doesn't matter where the "you"-ness comes from.

We don't know if it's still "you" and how we would tell.

E.g. someone can edit an electronic message to make the result act the same but contain a virus payload in addition. What would happen to the transporter transcription of you if that happened there?

In short, I don't see cartesian duality being relevant unless you posit that "you" won't be transcribed because the transporter transcribes only the physical atoms. If cartesian duality were fact, no transporter would work, and it would kill you and put your dead body at the transporter destination.

@Ethan wrote:

Did you see the new study published in Nature?

http://www.nature.com/articles/srep29901

Essentially what it says is the lunar bound astronauts who left the protection of the Earth's magnetosphere for only a few days were 400%-500% more likely to die from cardiovascular disease as compared to astronauts who only went to Low Earth Orbit.

We sent people when people were the only thing that could perform the task. We're not there any longer.