"We must regard it rather as an accident that the Earth (and presumably the whole solar system) contains a preponderance of negative electrons and positive protons. It is quite possible that for some of the stars it is the other way about." -Paul Dirac

You might think that the proton, made up of three spin=1/2 quarks, has a spin of 1/2 for that exact reason: you can sum three spin=1/2 particles together to get 1/2 out. But that oversimplified interpretation ignores the gluons, the sea quarks, the spin-orbit interactions of the component particles. Most importantly, it ignores the experimental data, which shows that the three valence quarks only contribute about 30% of the proton’s spin.

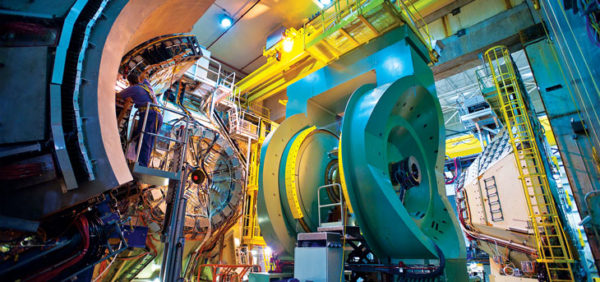

By colliding particles together at high energies inside a sophisticated detector, like Brookhaven's PHENIX detector at RHIC, have led the way in measuring the spin contributions of gluons. Image credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory.

By colliding particles together at high energies inside a sophisticated detector, like Brookhaven's PHENIX detector at RHIC, have led the way in measuring the spin contributions of gluons. Image credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory.

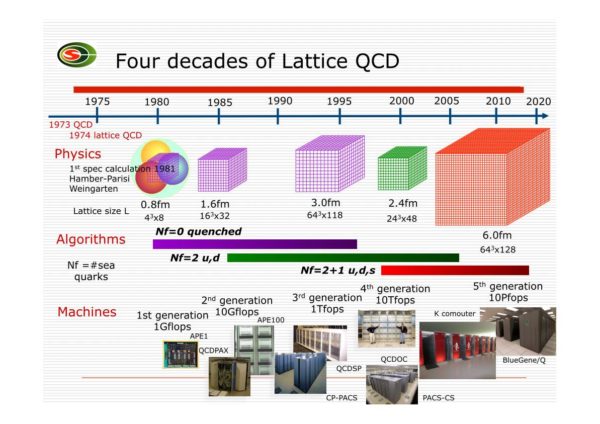

Our model of the proton has gotten more sophisticated over time, as advances in experiment and in Lattice QCD calculations have shown that the majority of the proton’s spin comes from the internal gluons, not from the quarks at all. The rest comes from orbital interactions, with the low-momentum gluons requiring a more sophisticated electron-ion collider to experimentally examine.

It's spin like charge, it's the 1/2 spin off the proton the same absolute size as the 1/2 spin off an elevation? If so, what explains the quantization to 1/2 integers. It didn't seem like the mechanisms described would require that.

Good the computers understand it. I would feel better if I also did. There must be a simple reason for precisely 1/2, independently of whether the gluons carry 60 or 59.5% of the spin.

@Klavs Hansen

I agree with you completely. It seems bizarre that with the quarks only contributing ~0.15 spin that everything else just coincidentally works out to give you the exact extra amount of spin down to the last decimal place to give you the expected answer. I'd think it is more likely evidence of the non-locality of spin. The number is the number based 100% on the quarks and the 'overhead' components just muddy where the vector exhibits.