castles

Supported by a grant from the King Gustavus Adolphus VI Foundation For Swedish Culture, osteologist Lena Nilsson has analysed the bones we collected during excavations last year at two Medieval strongholds. Two weeks with 19 fieldworkers at Birgittas udde produced only 0.4 kg of bones, because the site has no culture layers to speak of and the sandy ground has been unkind. But from the following two weeks at Skällvik Castle we brought home 32.7 kg of bones! And now Lena has looked at them all. Here are her reports:

Birgittas udde 2016

Skällvik Castle 2016

The reports are…

Our second week at Skällvik Castle proved a continued small-finds bonanza, and we also documented some pretty interesting stratigraphy.

More of everything in Building IV. In addition to more coins of Magnus Eriksson, dice and stoneware drinking vessels, we also found a lot of points for crossbow bolts. It's starting to look like the castle guards' day room! As for why we found crossbow bolts only inside one building and none outdoors in the bailey, I figure that they had been amassed there for re-fletching. The dark indoors find context and the undamaged sharp points show that the bolts did…

The famous royal castle of Stegeborg sits on its island like a cork in the bottleneck of the Slätbaken inlet (see map here). This waterway leads straight to Söderköping, a major Medieval town, and to the mouth of River Storån which would allow an invader to penetrate far into Östergötland Province's plains belt. The area's first big piece of public construction was 9th century fortifications intended to guard this entrypoint, in the shape of the Götavirke earthen rampart some ways inland and a wooden barrage at Stegeborg. This barrage was kept up for centuries, and indeed, the castle's name…

We spent Thursday afternoon backfilling. As I write this, only trench G remains open, and the guys there expect to finish soon. Here's some highlights of what we've learned during our second week at Birgittas udde.

Trench A in the outer moat demonstrated that the moat had a wide flat bottom, was not very deep and contains no lake sediments. Probably always a dry moat, providing material for the bank behind it. No Medieval finds.

Trench C: section through the deep inner moat.

Trench C in the inner moat demonstrated that this moat too had a wide flat bottom, but it was deeper and is full of…

Ulvåsa in Ekebyborna is a manor near Motala with two known major Medieval elite settlement sites. Excavations in 2002 proved that the unfortified Gamlegården site was established before AD 1100. The fortified Birgittas udde site has seen no archaeological fieldwork since 1924, when the main building's cellar was emptied and restored. Its date is only known to the extent that almost all moated sites of this kind in Sweden belong to the period 1250-1500. My current book project deals with Östergötland province's fortified sites of the High/Late Middle Ages, and so I decided to spend two weeks…

Myself, Ethan Aines and Mats G. Eriksson are proud to present our report on last year's fieldwork at Landsjö Castle, Kimstad parish, Östergötland. Lots of goodies there! Construction on the castle seems to have begun between 1250 and 1275, and the site was abandoned halfway through an extension project some 50-75 years later. We also found a Middle Neolithic fishing site and an Early Modern smallholding among the ruins.

Here on Sb: Landsjo 2015 Report (single-sided print-web, high res)

And on archive.org.

See also the report for 2014, the first documented excavations…

I spent last week in Denmark at a friendly, informative and rather unusual conference. The thirteenth Castella Maris Baltici conference (“castles of the Baltic Sea”) was a moveable feast. In five days we slept in three different towns on Zealand and Funen and spent a sum of only two days presenting our research indoors. The rest of the time we rode a bus around the area and looked at castle sites and at fortifications, secular buildings, churches and a monastery in four towns. Our Danish hosts had planned all of this so well that the schedule never broke down. Add to this that the food and…

Late Iron Age settlements are full of copper alloy objects, making them the preferred site category of metal detectorists. High Medieval castle sites, on the other hand, are quite poor in these often distinctive and informative finds.

The picture above shows all the copper alloy and lead that my team of ~15 found in over two weeks of excavations at Landsjö castle this past July, screening the dirt and using a metal detector in our trenches. Only seven objects! We collected 133 pieces of iron in that time, of which 77% are sadly nails in various states of completeness and thus not terribly…

2014 trenches A-E and rough locations of 2015 trenches F-H.

I write these lines on the day after we backfilled the last two trenches at Landsjö, packed up our stuff, cleaned the manor house, hugged each other and went our separate ways. It's an odd feeling to take apart the excavation machine while it still runs. It's been four fun and successful weeks!

Since my previous entry, written on Monday evening, we've done only three days of further excavation. Our main findings, to the extent that I have any comprehensive overview of them at the moment, relate to the culture layers sitting…

2014 trenches A-E and rough locations of 2015 trenches F-H.

Like Stensö, Landsjö Castle has half of a rare perimeter wall and is known to have been owned by a descendant of Folke Jarl – or rather, by his daughter-in-law, the widow of such a descendant. Last year we found that the high inner bailey has a previously unseen southern wall with a square tower at the east end, and we found five coins of AD 1250-75 in a deep layer that seem likely to date the castle's construction phase. But unlike Stensö, in three strategically placed trenches we found no trace of the missing bits of the…

Balancing available labour and a pre-decided excavation agenda against each other is not easy, particularly when you're doing investigative peek-hole fieldwork on a site whose depth and complexity of stratification you don't know much about. At Stensö we had two of three trenches and all five test pits backfilled in time for Wednesday lunch's on-site hot dog barbecue. Ethan Aines, Terese Liberg and three students stayed on to finish trench F, while myself, Mats Eriksson and six students moved to our new base at Landsjö Manor.

Trenches D and E and the test pits produced no big news after my…

This year's first week of fieldwork at Stensö Castle went exceptionally well, even though I drove a camper van belonging to a team member into a ditch. We're a team of thirteen, four of whom took part in last year's fieldwork at the site. All except me and co-director Ethan Aines are Umeå archaeology students. We're excavating the ruin of a castle that flourished in the 13th and 14th centuries. This year we have a very nice base at Smedstad, let to us by the genial B&B host Hans-Ola. But we cook our own meals, each day having its designated cooks and dishwashers, and in the evenings we…

Things are coming together with the post-excavation work for last summer's castle investigations so I'm putting some stuff on-line here.

I've submitted a paper detailing the main results to a proceedings volume for the Castella Maris Baltici symposium in Lodz back in May. There are no illustrations in the file, but you'll find all you need here on the blog in various entries tagged ”Castles”.

Osteologist Rudolf Gustavsson has completed his reports on the bones from the two sites (Landsjö – Stensö).

For the Dear Reader who doesn't read Swedish, a short summary of Rudolf's results is in order…

Landsjö castle. State of knowledge after the 2014 excavations.

I'm giving a talk on Landsjö castle to the Kimstad Historical Society next week, and while preparing my presentation I made a sketch plan of this summer's discoveries regarding the plan. The ruin just barely breaks the turf, so we didn't know much about the castle's layout beforehand except that it had a 60-metre straight stretch of perimeter wall along the west side and that it cannot have been rectangular.

Our main architectural discoveries in two July weeks of digging and clearing brush were as follows.

1. A wall divides the…

Deep in a single square metre of trench D at Landsjö castle, on the inner edge of the dry moat, we found five identical coins. Boy are they ugly. They're thin, brittle, made of a heavily debased silver alloy and struck only from one side; they bear no legend and the image at the centre is incomprehensible. But I love them anyway, because they offer a tight date: this coin type was struck for King Valdemar Birgersson c. 1250-75. And the first written mention of Landsjö dates from 1280, so it all works out.

Valdemar became king because he had an extremely powerful and ruthless father, the jarl…

A fun thing about historical archaeology, the archaeological study of areas and periods with abundant indigenous written documentation, is when the archaeology challenges the written record.

According to the patchily preserved historical sources, Landsjö hamlet was a seat of the high nobility in about 1280 but then became tenant farms no later than 1340. This means that the castle on Landsjö islet was probably in good defensible shape and inhabited in 1280 but not after 1340.

During last week's excavations we found a previously unknown strong wall delimiting the castle's high inner bailey,…

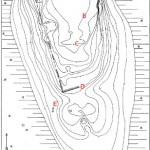

Christian Loven's plan of Landsjö Islet with letters marking on-going fieldwork.

Landsjö castle is on a high islet in the lake next to the modern manor house. Nobody ever goes there. The ruins are covered by vegetation and they're in bad shape: only along the western side of the islet do they rise even a metre above the rubble and accumulated forest mulch. Visible is a 59-metre N-S stretch of perimeter wall with a preserved corner at either end, and a shorter W-E stretch of perimeter wall from the south-western corner. Along the inside of the visible wall are vague suggestions of two…

With two days of digging and one day of backfilling left at Stensö Castle, trenches A and B have already given a rich harvest of new information.

The northern tower was a green ruin mound when we came to site. We now know that the tower was built entirely of greystone, it was round with a diameter of about 5.5 m, and it was planned and built together with the perimeter wall. The lost western half of the latter did not join the tower on a radial line. Instead more than half of the tower's circumference was outside of the perimeter wall, allowing flanking, where bowmen in the tower could strafe…

After four days of rubble removal in trench A, we found the south wall of Stensö Castle's northern tower. Note how the wall facing (left) ends, and a pale mass of wall core (lower right) emerges out of the tower. This is the castle's previously unseen western perimeter wall.

Our first week of two at Stensö is over, and already Chris, Fanny and Simon have made trench A answer the question we've asked of it. Way back in line with the trench's top edge on the flank of the northern tower's ruin mound, they've uncovered a neat wall face of dressed ashlar, and out of this tower wall projects an…

Medieval walls are usually shell walls, where you construct an inner and outer shell of finely fitted masonry while filling the space between them with a jumble of smaller stones and mortar. Usually the facing stones don't project much into the core. When the wall is allowed to erode, once the cap stones have fallen off, the facing starts to peel from the core one ashlar or brick at a time from the top down. Before the resulting rubble layer's top (rising) reaches the level of the wall's eroding top (descending), halting erosion, you'll see a ruinous wall that is thick and smooth-faced in its…