I saw the film Pawn Sacrifice the other day. It stars Tobey Maguire and Liev Schrieber as Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky. Serious chess movies don't come along very often, so I was excited to see it.

I liked it! What's not to like about a movie where the actors deliver lines like, “They're playing a line of the Nimzo,” or “Fischer's playing the Benoni, he's never done that before. The Russians think it's suicide.” “Is it suicide?” “Oh yes...” Chess jargon? Cool! It's mostly accurate too, though they certainly took a few liberties here and there. I do fault them for two things, though.

The first is that the film drags a bit. It's basically a sequence of scenes of Fischer being great at chess, alternating with scenes of Fischer being crazy. That's a pity, because there was a lot of human drama surrounding his rise to the top that could have been included.

The second is that they never mentioned that Bobby Fischer went to high school with my mother.

Those are nitpicks. The film is well worth seeing. In fact, I might go see it a second time. (But I have to see The Martian first.)

The big world chess championship match between Fischer and Spassky took place in 1972, which is long enough ago to forget what a big deal it was. Spassky represented the greatest chess empire in the history of the world, while Fischer was just a one-man-show from Brooklyn. The match was seen as having major Cold War overtones. When it seemed like Fischer might have one of his temper tantrums and withdraw from the match, no less than Henry Kissinger called him, pleading with him to proceed.

Stephen Jay Gould was fond of describing Joe DiMaggio's 56 game hitting streak as simply the greatest and most statistically improbable achievement in the entire history of sport. If chess is included among the sports, then Fischer has two accomplishments that make DiMaggio look like a piker.

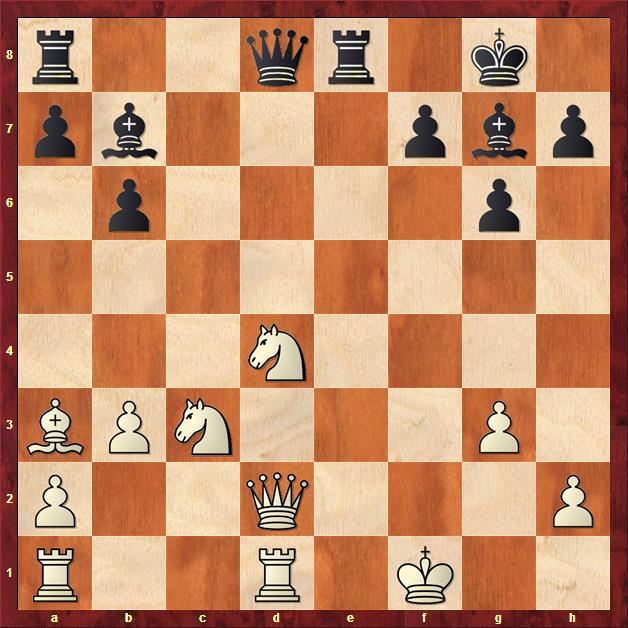

Fischer won the 1963-1964 US Chess Championship with a perfect score of 11 wins, no losses, no draws. Along the way, he played moves like this:

Playing white was long-time New York Times chess columnist Robert Byrne. Fischer was black. A quick count of the material shows that black has sacrificed a piece, but for what exactly? The commentators in the press room, strong players all, were generally of the opinion that Fischer had lost his mind.

But Fischer was only crazy away from the chessboard. He played 21. ... Qd7!, and Byrne resigned. The threat is 22. ... Qh3+ 23. Kg1 Bxd4+ 24. Qxd4 Qg2 mate. What is white to do? He has a few options, but nothing works. For example, 22. Qf2 Qh3+ 23. Kg1 Re1+! 24. Rxe1 Bxd4 with mate soon to come.

But the second achievement made even this look like nothing. Over the course of the Interzonal tournament in Palma de Mallorca in 1970, then his candidates matches with Taimanov, Larsen, and Petrosian, Fischer rattled off twenty straight wins against the top players of the day. This is unheard of.

It gets even better. Fischer won the first game in his match against Petrosian (the winner of which would go on to play Spassky). But Petrosian came back to win the second (breaking the twenty game streak), and then nearly won the third game before being forced to concede the draw. It seemed that Fischer was back on his heels. But after two further draws, Fischer rattled off four straight wins.

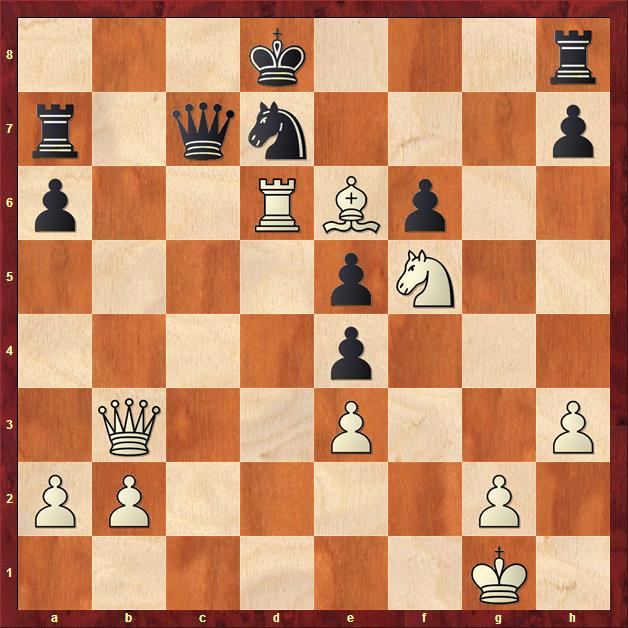

There are lots of good Fischer stories. At the Varna Olympiad in 1962, Fischer was scheduled to play the great Argentine grandmaster Miguel Najdorf. Before the game Fischer is said to have remarked, “I'll crush him in twenty-five moves.” Here's what happened:

This came out of Najdorf's own variation of the Sicilian Defense. White is about to play his fourteenth move. Here Fischer noticed that black has only one active piece. So he decided to snap it off, even though that meant investing some material. Play continued 14. Rxe4 dxe4 15. Nf5, and over the next few moves white's remaining pieces effortlessly arrived at good squares, while black was just tied up in knots. After white's 24th move the position was this:

Splat. It's Armageddon on d7, and 24. ... Rb7 25. Qa4 does not help. Najdorf resigned, one move faster than Fischer predicted.

Actually, Najdorf once paid Fischer a great compliment in saying, “Fischer has no style.” His idea was that some players, like Kasparov and Tal, prefer swashbuckling tactics and always look for ways to attack, while others, like Karpov and Petrosian, prefer slow positional crushes. But Fischer just calmly assessed the position and more often than not played the best move.

Now for some of the human drama I mentioned. Chess was a big thing for the Soviets of that era, and the state poured enormous money and resources into maintaining their dominance. As you can imagine, Fischer was giving them fits. With the break up of the Soviet Union, all of those Soviet players were suddenly free to talk about their experiences, and many internal documents from the relevant authorities became publicly available. The result was a remarkable book I have on my shelf called Russians Versus Fischer.

In the first round of the candidate's matches, Fischer played Mark Taimanov, who in addition to being a great chessplayer (the Taimanov variation of the Sicilian Defense remains a popular opening to this day), was also a concert pianist. Fischer won one of the early games by playing a clever novelty in the opening. Taimanov describes their conversation after the game:

When, after the game, I asked Bobby about this prepared line of his, he replied modestly that the idea was not his--he had come across it in the monograph of the Soviet master Alexander Nikitin, in a footnote! Fischer had only to put it to good use.

It is unforgivable that I, an expert in the Sicilian, should have missed this theoretically significant observation of a countryman and Fischer had uncovered it in a book in a foreign language!

Long story short, Fischer won the match with six wins, no losses, no draws. Fischer was gracious in victory: “The 6:0 score does not do justice to my opponent. The struggle was far more intense than the score alone shows. It is easier to be a gentleman after winning than after losing, and therefore I want to congratulate my adversary.”

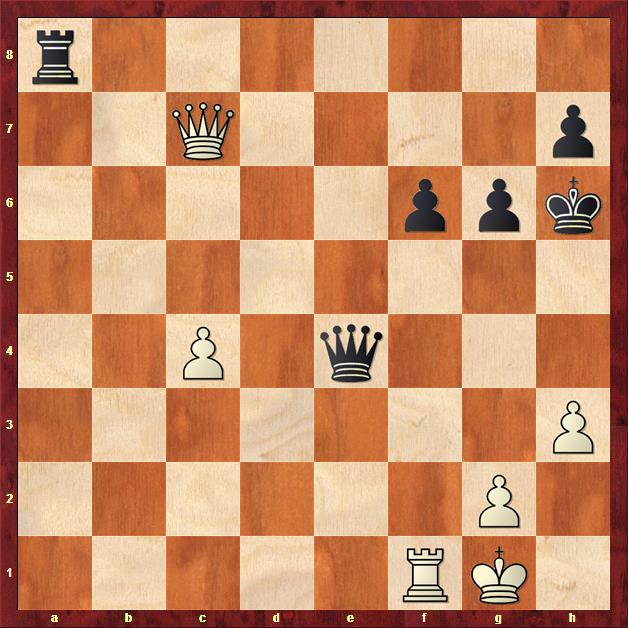

Indeed, in one of the games Taimanov was stone cold winning, but missed the decisive move before going on to lose. In two other games he held an advantage, and Fischer won two games on crass blunders by Taimanov. Like this one:

The game really should end in a draw at this point. But Taimanov stopped paying attention and took the free pawn on f6, playing 46. Rxf6. He describes thinking that the endgame was still a dead draw after 46. ... Ra2 by black, but that at least he would have the moral satisfaction of being up a pawn when the draw was agreed.

Taimanov was already down 4:0 in the match. At this point Fischer said, “I'm sorry,” and played 46. ... Qd4+. After 47. Rf2 Ra1+ white will lose his rook. Taimanov resigned for the fifth time. To be blunt, most amateur players would not have made this mistake.

Things did not go well for Taimanov after returning to the Soviet Union. This is worth quoting at length:

The match with Fischer was unquestionably the most important and most memorable event in my long chess career. Not only because I was one of the last players who had the honor to cross swords with the legendary and most enigmatic master of modern times but also because the outcome of the match sparked a series of unpredictable events, which dramatically changed the course of my chess career and even my private life.

Whereas before the match I enjoyed the reputation of a model citizen in the USSR, hailed not only as a prominent chessplayer but also as a professional pianist and journalist...after the Vancouver defeat I suddenly found myself the target of devastating criticism from all quarters: from the communist party's Central Committee to my own party cell.

No holds were barred. My honorary title of Merited Master of Sports was taken away from me, I was kicked out of the USSR national team (with dire financial consequences), for almost two years I was forbidden to take part in tournaments abroad. I was not allowed to have my articles published or even to appear in concerts as a pianist. All this amounted to a civic execution.

It appeared that some big shot in the Kremlin had decided that a Soviet grandmaster could not simply lose to an American-this was an impossibility on ideological grounds alone. Ipso facto, my defeat had to be a premeditated act in support of US imperialism.

Of course, the real reason for punishing me had to be camouflaged: after all, what would the rest of the world's reaction be to the persection of a prominent grandmaster just for losing a match, even to an American? So a formal pretext for my public censure was found: it was an alleged breach of customs regulations. Solzhenitsyn's book The First Circle was discovered in my luggage by customs officials at Sheremetyevo airport, after an unusually thorough search. Although at the time the disgraced author was not yet stripped of his Soviet citizenship and was living in a Moscow suburb, for want of anything better the authorities decided to charge me with bringing banned literature into the country...

The Chief of Sheremetyevo Customs, an elderly man who knew me, said: You should have been more careful, Mr. Taimanov. If your score against Fischer had been better, I would be prepared to carry Solzhenitsyn's collected works for you...

That was not the end of the fault-finding. The FIDE President Dr. Euwe had asked me to deliever a letter and 1,100 Guilders in royalties to my friend, Grandmaster Salo Flohr. The letter ran, harmlessly enough: Dear Salo, I am sending you the money for the articles published in the Dutch journal...followed by a few kind words making it clear that I had nothing to with this communication or money. Nonetheless, the letter was used against me.

What followed was a Sports Committee meeting. The ranking officials in attendance had copies of the translated letter before them. By the expression on their faces I might have robbed the Bank of Canada and smuggled millions of dollars into the country. The Minister for Sports Pavlov, looking very angry, charged me with contraband and the reading of books that he would be disgusted even to touch. The sentence you already know-I was deprived of everything they could deprive me of. Pavlov even tried to take away my title of international grandmaster, but stopped short saying: We cannot do that, the title was not awarded by us.

I recall the bitter joke of my old friend the great musician Rostropovich: Do you now that Solzhenitsyn is in trouble...they have found Taimanov's The Nimzovich Defense among his belongings!

Help came from an unexpected quarter: Bent Larsen lost to Fischer 0:6, the same score. This had a sobering effect on my persecutors: they could not dream of suspecting a Danish grandmaster of collusion with the imperialists!

Altough this blunted the attacks against me somewhat, for many more years I felt the effects of official displeasure.”

This post has gone too long, so I'll wrap things up. Fischer's opponent for the finals would be the winner of the match between Victor Korchnoi and Tigran Petrosian. The first eight games of the match had been drawn, and at this point Fischer had completed his demolition of Larsen. The Soviet chess authorities decided that Petrosian had the better chances against Fischer, so Korchnoi was ordered to throw the match.

Fischer played Petrosian, and spanked him.

Then he played Spassky, and spanked him too.

GREAT stuff! If only Fischer had he been more personable & more of a crowd-pleaser no telling what he might've accomplished in life; such a mix of glory and sadness as it was.

I'm looking forward to seeing the movie. In July of 1966 I had a summer job digging ditches outside a hotel in Santa Monica where the 2nd Piatagorsky chess tournament was underway. Fischer used to walk back and forth beside my ditch talking to his second, William Lombardy, so I got a chance to overhear them. Lombardy kept talking about nuts and bolt chess stuff—I used to play in amateur tournaments and could understand the lingo—but Fischer simply ranted on and on about how he was going to crush Spassky and demolish Nadjorf and wipe out Petrosian and on and on. He sounded a bit like Mohammad Ali back when he was still Cassius Clay except that the boxer was playing to the cameras with his trash talk and Fischer apparently couldn't turn it off. After listening to him, I never had any trouble believing that Fischer was off in the head.

I remember the Reykjavik match as much for the off screen tension and psychological warfare as for the playing itself.

Hey, thanks for the book recommendation! I didn't even know it existed.

Fischer to me is practically the definition of the word tragedy. Certainly he was correct in his perception of the Russian control-freak Chess Federation. Heck, the Russian society as a whole -- just look at what they did to Shostakovich, quite possibly the very greatest music composer of the 20th century ( check out his string quartets if you don't believe me).

But his hatreds just overwhelmed him and deprived the chess world of such treasures.

It might have been.

Then there is the musical Chess by Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus, which is loosely based on Fischer vs Russians. Great music, but perhaps not so many details on chess.

Bobby has always been an idol to me. I remember 1972 well even though I am an average player at best. Also enjoyed the movie. P. S. The reason that my email is what it is...is because I love CHESTNUTS.