tags: evolutionary biology, behavioral ecology, molecular ecology, personality, novelty seeking, exploratory behavior, dopamine receptor, dopamine receptor D4 gene, DRD4 gene polymorphism, ornithology, birds, Great Tit, Parus major, researchblogging.org,peer-reviewed research, peer-reviewed paper

Bold or cautious? Individuals with a particular gene variant are very curious --

but only in some populations.

Image: Henk Dikkers.

Research suggests that personality variations are heritable in humans and other animal species, and there are many hypotheses as to why differences in personality exist and are maintained. One approach for investigating the heritability of personality lies in identifying which genes underlie specific personality traits so scientists can then determine how the frequencies of specific variants of personality-related genes change in both space and time as well as in relation to changing environmental influences.

For example, in humans, the best-studied "personality gene" is the dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4) gene, which is involved in motivation, pleasure, cognition, memory, and learning. The DRD4 gene encodes a receptor protein that binds to the neurotransmitter, dopamine. When DRD4 binds dopamine, this interaction influences novelty seeking and exploratory behavior in a range of species, including humans and birds.

As is true for most genes, there are variants -- known as polymorphisms -- of DRD4. These polymorphisms alter the binding dynamics of DRD4 for its ligand, dopamine: different variants bind dopamine more or less tightly, and this difference in binding affinity alters behavior. For example, previous research has suggested that variations in the DRD4 gene in the Great Tit, Parus major, are the underlying reason that some of these birds are more curious than others [DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.006]. This association was originally noted and tested in 2007 in only one population of Great Tits that were hand-raised captives [DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0337].

But association studies such as these rarely show consistent correlations between genes and behavior across populations and environments. Thus, it was decided to repeat this work with large numbers of wild Great Tits from four distantly located populations.

"It was important to confirm the association between the DRD4 variants and exploratory behavior in the original population," explained Bart Kempenaers, director at the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Germany.

To repeat this work, Dr Kempenaers and an international team of scientists captured young adult birds captured in the field (Figure 1) from four different populations -- including wild relatives of the original group of captive Great Tits studied; Westerheide.

Fig. 1 Locations of four wild great tit populations investigated for associations between exploratory behaviour and DRD4 SNP830 and ID15 polymorphisms. Populations are Westerheide (WH), Lauwersmeer (LM), Boshoek (BH) and Wytham Woods (WW).

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04518.x

To do this work, the team captured only wild birds that had been individually marked with color-coded leg bands when nestlings, so they knew the precise age and family relationships for each bird. After capture, the birds were kept overnight in individual cages adjacent to the test chamber. The following morning, each bird was separately released into the test chamber, a novel environment containing five artificial "trees," and the bird's behavior was documented. The frequency of hops and flights between the perches on the artificial trees were counted and scored as a proxy for exploratory behavior (pictured below).

Test chamber containing five artificial "trees" where the birds' exploratory behaviors in a novel environment were assessed.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04518.x

Image: Anne Rutten.

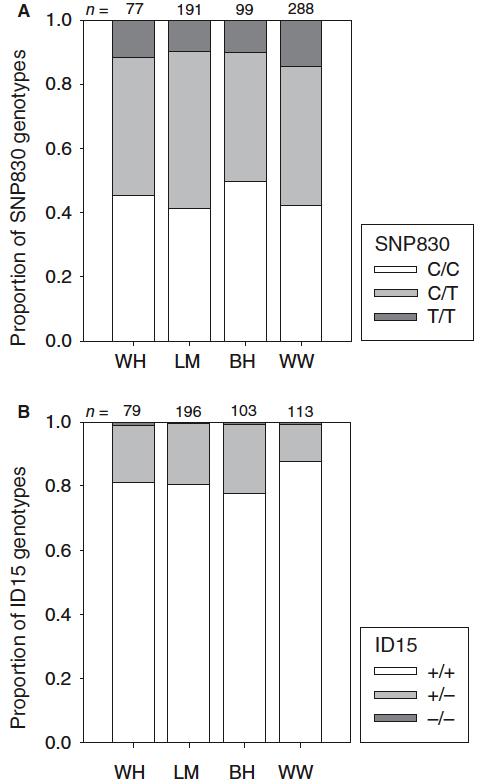

Prior to releasing the birds in their respective homes, a feather or a small blood sample was collected and then the two DRD4 gene variants (SNP830 and ID15) were identified for each of the 491 individual birds. When the team analyzed the genetic data, they were surprised to learn that the frequency of the SNP830 and ID15 polymorphisms of DRD4 were the same in all of the populations (Figure 2):

Fig. 2 Proportions of DRD4 SNP830 (A) and ID15 (B) genotypes in four wild great tit populations: Westerheide (WH), Lauwersmeer (LM), Boshoek (BH) and Wytham Woods (WW).

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04518.x

Interestingly, although the team found that DRD4 polymorphisms were statistically the same, the average exploratory scores differed significantly between the four populations studied (Figure 3):

Fig. 3 Box plots of exploration scores (corrected for seasonal trend) of four wild great tit populations: Westerheide (WH), Wytham Woods (WW), Boshoek (BH), and Lauwersmeer (LM). Box plots indicate medians and the 10th, 25th, 75th and 90th percentiles; 5th and 95th percentiles are indicated by the filled circles; the open circles indicate the population means.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04518.x

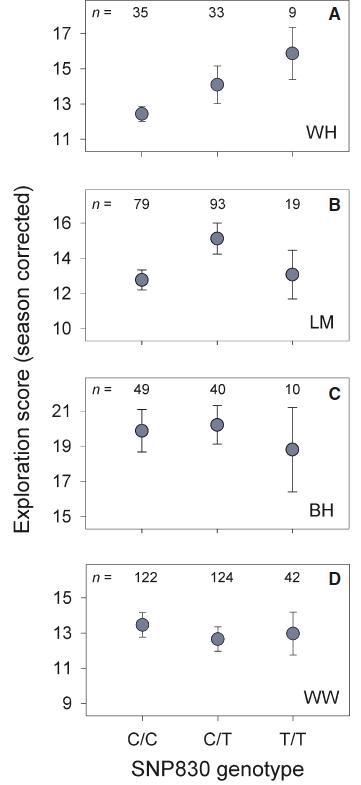

To their surprise, the team found that exploratory behavior demonstrated by the Westerheide population was significantly associated with SNP830 genotype, while birds from the other three populations showed either a weak or nonexistent correlation (Figure 4):

Fig. 4 Exploration scores (corrected for seasonal trend; means with standard errors) of wild great tits of four populations in relation to the DRD4 SNP830 genotype. Exploration scores were significantly associated with SNP830 genotype in Westerheide.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04518.x

Additional analyses showed that the strength of this association was not different between the original 2007 group of hand-raised birds and the free-living birds from the population tested in this follow-up study.

"But," Dr Kempenaers cautioned, "we do not yet understand the differences between populations."

They also found that the relationship between the SNP830 genotype and exploratory behavior was independent of the sex of individuals.

"To our knowledge, this is the most extensive study of gene variants underlying personality-related behavioral variation in a free-living animal to date, and the first to compare different wild populations", said Peter Korsten, first author on the paper and a former member of Bart Kempenaers' lab.

These differences between avian populations are a reiteration of the age-old "nature versus nurture" controversy. Basically, an individual gene's influence on behavior is usually subtle and very likely occurs in concert with many other still unidentified genes. Additionally, a gene's located on a chromosome is important: close neighbors on the DNA strand tend to travel together during genetic reassortment, even when their functions are quite different, so these findings could be a "location artifact." Further, genetic effects probably play a small role in personality when compared to the strong influence of the environment, especially in species such as birds where learning is so vitally important to their socialization.

"Perhaps further investigation of Great Tit populations could shed some light on the differences in outcome in the human populations," suggested Dr Korsten optimistically.

For example, several polymorphisms in the DRD4 gene sequence have been identified in humans that are associated with certain mental health and cognitive disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Call me a skeptic, but I do not share Dr Korsten's optimism.

Source:

Korsten, P., Mueller, J., Hermannstädter, C., Bouwman, K., Dingemanse, N., Drent, P., Liedvogel, M., Matthysen, E., van Oers, K., van Overveld, T., Patrick, S., Quinn, J., Sheldon, B., Tinbergen, J., & Kempenaers, B. (2010). Association between DRD4 gene polymorphism and personality variation in great tits: a test across four wild populations. Molecular Ecology, 19 (4), 832-843 DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04518.x

Most. Misleading. Title. Ever.

Not that misleading. If you were thinking of a great rack, aka human female mammaries, you could easily make a not so great jump to the conclusion that 'Within a population/culture/region individuals with similar phenotypes tend to express similar personalities, but that same phenotype in a different place will most certainly have different personalities from your previous population.'

Right?

not even nearly, Chris. there used to be a webpage around titled "watch these great tits", leading to a webcam of the inside of a birdhouse --- the ornithologist's version of rickrolling.

(the hatchlings were pretty cute, though.)

tits are among the world's cutest birds.

:)

How cute are boobies, though?

They are about as cute as hooters.

At the risk of stoking the fires of innuendo further, Titmouse (the original name of these birds) derives from the Middle English "tit" meaning small and the old German "mees" also meaning small so the bird is really "smallsmall". Anagram says "Timeouts"