![]() We saw that the littlest differences can lead to dramatic variations when we looked at the wide variety in dogs. But despite their differences, all breeds of dogs are still the same species as each other and their ancestor. How do species split? What causes speciation? And what evidence do we have that speciation has ever occurred?

We saw that the littlest differences can lead to dramatic variations when we looked at the wide variety in dogs. But despite their differences, all breeds of dogs are still the same species as each other and their ancestor. How do species split? What causes speciation? And what evidence do we have that speciation has ever occurred?

Critics of evolution often fall back on the maxim that no one has ever seen one species split into two. While that's clearly a straw man, because most speciation takes far longer than our lifespan to occur, it's also not true. We have seen species split, and we continue to see species diverging every day.

For example, there were the two new species of American goatsbeards (or salsifies, genus Tragopogon) that sprung into existence in the past century. In the early 1900s, three species of these wildflowers - the western salsify (T. dubius), the meadow salsify (T. pratensis), and the oyster plant (T. porrifolius) - were introduced to the United States from Europe. As their populations expanded, the species interacted, often producing sterile hybrids. But by the 1950s, scientists realized that there were two new variations of goatsbeard growing. While they looked like hybrids, they weren't sterile. They were perfectly capable of reproducing with their own kind but not with any of the original three species - the classic definition of a new species.

For example, there were the two new species of American goatsbeards (or salsifies, genus Tragopogon) that sprung into existence in the past century. In the early 1900s, three species of these wildflowers - the western salsify (T. dubius), the meadow salsify (T. pratensis), and the oyster plant (T. porrifolius) - were introduced to the United States from Europe. As their populations expanded, the species interacted, often producing sterile hybrids. But by the 1950s, scientists realized that there were two new variations of goatsbeard growing. While they looked like hybrids, they weren't sterile. They were perfectly capable of reproducing with their own kind but not with any of the original three species - the classic definition of a new species.

How did this happen? It turns out that the parental plants made mistakes when they created their gametes (analogous to our sperm and eggs). Instead of making gametes with only one copy of each chromosome, they created ones with two or more, a state called polyploidy. Two polyploid gametes from different species, each with double the genetic information they were supposed to have, fused, and created a tetraploid: an creature with 4 sets of chromosomes. Because of the difference in chromosome number, the tetrapoid couldn't mate with either of its parent species, but it wasn't prevented from reproducing with fellow accidents.

This process, known as Hybrid Speciation, has been documented a number of times in different plants. But plants aren't the only ones speciating through hybridization: Heliconius butterflies, too, have split in a similar way.

It doesn't take a mass of mutations accumulating over generations to create a different species - all it takes is some event that reproductively isolates one group of individuals from another. This can happen very rapidly, in cases like these of polyploidy. A single mutation can be enough. Or it can happen at a much, much slower pace. This is the speciation that evolution is known for - the gradual changes over time that separate species.

But just because we can't see all speciation events from start to finish doesn't mean we can't see species splitting. If the theory of evolution is true, we would expect to find species in various stages of separation all over the globe. There would be ones that have just begun to split, showing reproductive isolation, and those that might still look like one species but haven't interbred for thousands of years. Indeed, that is exactly what we find.

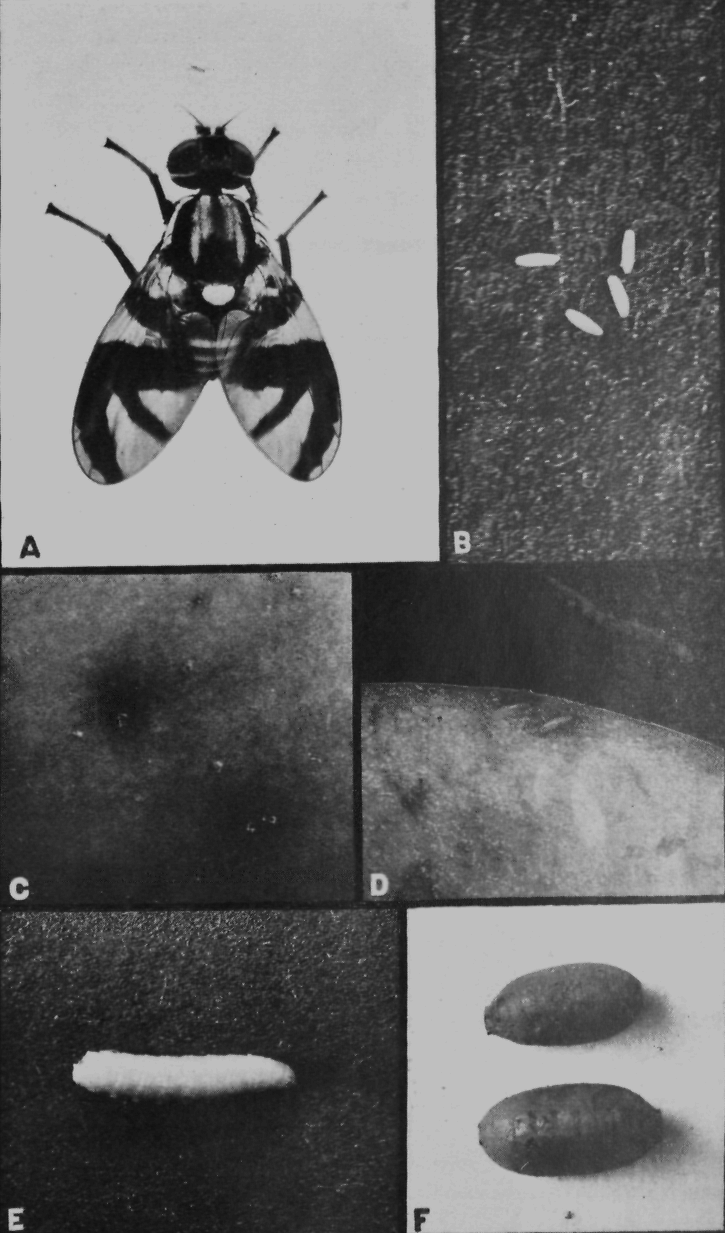

The apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomonella is a prime example of a species just beginning to diverge. These flies are native to the United States, and up until the discovery of the Americas by Europeans, fed solely on hawthorns. But with the arrival of new people came a new potential food source to its habitat: apples. At first, the flies ignored the tasty treats. But over time, some flies realized they could eat the apples, too, and began switching trees. While alone this doesn't explain why the flies would speciate, a curious quirk of their biology does: apple maggot flies mate on the tree they're born on. As a few flies jumped trees, they cut themselves off from the rest of their species, even though they were but a few feet away. When geneticists took a closer look in the late 20th century, they found that the two types - those that feed on apples and those that feed on hawthorns - have different allele frequencies. Indeed, right under our noses, Rhagoletis pomonella began the long journey of speciation.

The apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomonella is a prime example of a species just beginning to diverge. These flies are native to the United States, and up until the discovery of the Americas by Europeans, fed solely on hawthorns. But with the arrival of new people came a new potential food source to its habitat: apples. At first, the flies ignored the tasty treats. But over time, some flies realized they could eat the apples, too, and began switching trees. While alone this doesn't explain why the flies would speciate, a curious quirk of their biology does: apple maggot flies mate on the tree they're born on. As a few flies jumped trees, they cut themselves off from the rest of their species, even though they were but a few feet away. When geneticists took a closer look in the late 20th century, they found that the two types - those that feed on apples and those that feed on hawthorns - have different allele frequencies. Indeed, right under our noses, Rhagoletis pomonella began the long journey of speciation.

As we would expect, other animals are much further along in the process - although we don't always realize it until we look at their genes.

Orcas (Orcinus orca), better known as killer whales, all look fairly similar. They're big dolphins with black and white patches that hunt in packs and perform neat tricks at Sea World. But for several decades now, marine mammalogists have thought that there was more to the story. Behavioral studies have revealed that different groups of orcas have different behavioral traits. They feed on different animals, act differently, and even talk differently. But without a way to follow the whales underwater to see who they mate with, the scientists couldn't be sure if the different whale cultures were simply quirks passed on from generation to generation or a hint at much more.

Now, geneticists have done what the behavioral researchers could not. They looked at how the whales breed. When they looked at the entire mitochondrial genome from 139 different whales throughout the globe, they found dramatic differences. These data suggested there are indeed at least three different species of killer whale. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the different species of orca have been separated for 150,000 to 700,000 years.

Now, geneticists have done what the behavioral researchers could not. They looked at how the whales breed. When they looked at the entire mitochondrial genome from 139 different whales throughout the globe, they found dramatic differences. These data suggested there are indeed at least three different species of killer whale. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the different species of orca have been separated for 150,000 to 700,000 years.

Why did the orcas split? The truth is, we don't know. Perhaps it was a side effect of modifications for hunting different prey sources, or perhaps there was some kind of physical barrier between populations that has since disappeared. All we know is that while we were busy painting cave walls, something caused groups of orcas to split, creating multiple species.

There are many different reasons why species diverge. The easiest, and most obvious, is some kind of physical barrier - a phenomenon called Allopatric Speciation. If you look at fish species in the Gulf of Mexico and off the coast of California, you'll find there are a lot of similarities between them. Indeed, some of the species look almost identical. Scientists have looked at their genes, and species on either side of that thin land bridge are more closely related to each other than they are to other species, even ones in their area. What happened is that a long time ago, the continents of North and South America were separated, and the oceans were connected. When the two land masses merged, populations of species were isolated on either side. Over time, these fish have diverged enough to be separate species.

Species can split without such clear boundaries, too. When species diverge like the apple maggot flies - without a complete, physical barrier - it's called Sympatric Speciation. Sympatric speciation can occur for all kinds of reasons. All it takes is something that makes one group have less sex with another.

For one species of Monarch flycatchers (Monarcha castaneiventris), it was all about looks. These little insectivores live on Solomon Islands, east of Papua New Guinea. At some point, a small group of them developed a single amino acid mutation in the gene for a protein called melanin, which dictates the bird's color pattern.  Some flycatchers are all black, while others have chestnut colored bellies. Even though the two groups are perfectly capable of producing viable offspring, they don't mix in the wild. Researchers found that the birds already see the other group as a different species. The males, which are fiercely territorial, don't react when a differently colored male enters their turf. Like the apple maggot flies, the flycatchers are no longer interbreeding, and have thus taken the first step towards becoming two different species.

Some flycatchers are all black, while others have chestnut colored bellies. Even though the two groups are perfectly capable of producing viable offspring, they don't mix in the wild. Researchers found that the birds already see the other group as a different species. The males, which are fiercely territorial, don't react when a differently colored male enters their turf. Like the apple maggot flies, the flycatchers are no longer interbreeding, and have thus taken the first step towards becoming two different species.

These might seem like little changes, but remember, as we learned with dogs, little changes can add up. Because they're not interbreeding, these different groups will accumulate even more differences over time. As they do, they will start to look less and less alike. The resultant animals will be like the species we clearly see today. Perhaps some will adapt to a lifestyle entirely different from their sister species - the orcas, for example, may diverge dramatically as small changes allow them to be better suited to their unique prey types. Others may stay fairly similar, even hard to tell apart, like various species of squirrels are today.

The point is that all kinds of creatures, from the smallest insects to the largest mammals, are undergoing speciation right now. We have watched species split, and we continue to see them diverge. Speciation is occurring all around us. Evolution didn't just happen in the past; it's happening right now, and will continue on long after we stop looking for it.

Soltis, D., & Soltis, P. (1989). Allopolyploid Speciation in Tragopogon: Insights from Chloroplast DNA American Journal of Botany, 76 (8) DOI: 10.2307/2444824

McPheron, B., Smith, D., & Berlocher, S. (1988). Genetic differences between host races of Rhagoletis pomonella Nature, 336 (6194), 64-66 DOI: 10.1038/336064a0

Uy, J., Moyle, R., Filardi, C., & Cheviron, Z. (2009). Difference in Plumage Color Used in Species Recognition between Incipient Species Is Linked to a Single Amino Acid Substitution in the Melanocortinâ1 Receptor The American Naturalist, 174 (2), 244-254 DOI: 10.1086/600084

Phillip A Morin1, Frederick I Archer, Andrew D Foote, Julie Vilstrup, Eric E Allen, Paul Wade, John Durban, Kim Parsons, Robert Pitman, Lewyn Li, Pascal Bouffard, Sandra C Abel Nielsen, Morten Rasmussen, Eske Willerslev, M. Thomas P Gilbert, & Timothy Harkins (2010). Complete mitochondrial genome phylogeographic analysis of killer whales (Orcinus orca) indicates multiple species Genome Research

So full of win.

I think it's also worthwhile to note that de-speciation is also occurring constantly. Species that were separated by habits or habitat that are no longer separated can start inter-breeding. The Grants showed this remarkably well looking at the finches in the Galapagos (insert a plug for "The Beak of the Finch", one of the best science books I've ever read). Speciation that hasn't gone to extremes (producing sterile hybrids or no offspring at all) is erasable.

Evolution isn't moving "forward" toward a goal, it's random chance that wobbles in both directions!

I'm most familiar with freshwater fish species in the New World. I think most of their speciation is allopatric speciation. Suppose, in the field, I see two somewhat different allopatric populations which I think to represent a single species. Is speciation occurring? One can only speculate. The two populations could persist and diverge such that we now have two species. They could come into contact and merge together in such a way that we could not deduce they had ever been separated. Or, perhaps most likely, one or both goes extinct. So I think speciation events of this kind are to be inferred rather than observed. Just a comment, not a criticism of your post.

Good post. Thanks.

I am unaware of anyone doing any work on the question, but looking at the differences between [for example] a chihuahua and a St. Bernard I am tempted to think that dogs may be approaching the outer edge of their unity as a species. It might not take much more artificial selection to turn dogs into a quasi-ring species, a non-mutually inter-fertile collection of canines that cannot and would not interbreed, but who can and will interbreed with other dogs who can breed with other dogs who can breed with the other non-inter-fertile dog breeds.

all look fairly similar.

that's a major issue with arguing with creationists. what they want to see is visible body plan changes. the kind of stuff that literally takes millions of years.

i think the 'species concepts' debates are interesting, but view species instrumentally anyhow. by contrast, creationists believe in species as kinds which qualities which make them fundamentally different. in other words, they're still operating with an aristotelian framework.

My impression is that that's a very vertebrate-centric view: the people who say that sympatric speciation is important tend to be entomologists (NB this is just my impression, I haven't looked at it seriously). I'm not going to take a position on who's right!

Sean Carroll in The Making of the Fittest describes the speciation story that produced the curious ice fish of the Antarctic. The land bridge joining Antarctica to the tip of South America disappeared changing the ocean's circulation and dropping the water temperature drastically so that fish couldn't survive. But DNA errors produced fish lacking haemoglobin and scales, and with antifreeze molecules in their blood. The resultant ice fish have less viscous non-freezing blood and absorb some oxygen through their skin. It took 20-40 million years for these adaptations to appear, but what I like is that the changes were the result of fluke errors in the exisiting DNA.

Hmmm!: "Sympatric speciation can occur for all kinds of reasons. All it takes is something that makes one group have less sex with another." You imply here that the "all kinds of reasons" are the set of reasons that exclude having sex (technically prezygotic isolation). But you should know that sympatric speciation can also occur even in forms that can still have sex (technically known as postzygotic isolation).

love!

Christie, love this blog. Your writing is excellent.

With all the dog breeding we humans do, are we seeing any speciation among dogs? Has anyone come up with a breed that crosses only with itself? (maybe we wouldn't know because it wouldn't be mated with relatives and the new species would die out...)

Has anyone done a DNA analysis on those Tea Party people? I strongly suspect that they are, in fact, a separate species that only recently split from homo sapiens.

How is this known? Is it known? Has it actually been tested? Say, Chihuahua and Great Dane...