"Everything that slows us down and forces patience, everything that sets us back into the slow circles of nature, is a help." -May Sarton

It's unbelievable how much more amazing the world becomes in slow-motion. You've probably seen some high speed cameras that shoot at astounding frame rates, such as the video (below) of a popping water balloon, at literally ten thousand frames-per-second.

Compared to normal television or film, where frame-rates are typically only 24 to 30 frames-per-second, it's no wonder that this appears spectacular to our eyes! Played back at a rate where a few mere milliseconds get stretched into entire seconds, we can see some amazing details. Single still photos, such as the one of a bullet below, can be taken using this ultra-high-speed technology, grabbing amazing physical detail that would be missed by our pathetically slow neurons.

But even with the highest-speed cameras ever engineered -- which may approach one million frames-per-second (fps) -- we still have no hope of seeing how individual light pulses work. After all, light moves at a whopping 300,000 km/s; even taking a million fps means that your photons will move something like 300 meters (1,000 feet) in between individual frames, so how could we possibly expect to see a light pulse illuminating an object? (That is, going from dark to light back to dark again.)

In theory, this isn't hard. We think we know how individual, visible light pulses ought to bounce off of objects: it's simple geometry for photons traveling at the speed of light, where the photons would simply register with your eyes (or with the camera's electronics) when they reach you.

But in practice, if you wanted to catch light in the process of illumination, you'd need something that could effectively take pictures at around a trillion frames-per-second, or 1012 fps. If you wanted to create a high-speed camera that could do this, it would need to take a picture every trillionth of a second.

The physics of your system, however, will have none of that. In a trillionth of a second, light can only move 300 microns, and electrons -- which is what moves in your electronics -- are even slower. Even the smallest, shortest distances we could design to accomodate the taking of a photograph and the resetting of the interior electronics is nowhere close to the required distances to take pictures at that rate!

And yet, this video exists, and is real, not computer generated.

Others have noted that you can't have a camera really take pictures at 1,000,000,000,000 fps, so -- if you're anything like me -- you've got to be curious as to how they made this.

So here's the science of how you do it, and it's one of the coolest physics tricks I've ever heard of! It's a trick, believe-it-or-not, that's based on the way that old television sets work.

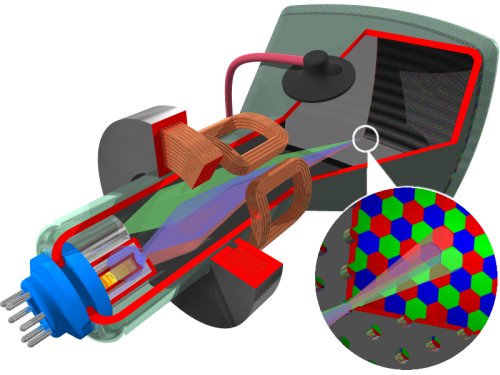

Rather than shooting light, as you might think from the diagram above, old cathode-ray-tube television sets fire electrons at the screen! Right up against the screen are fluorescent materials (known as phosphors) capable of emitting red, green, or blue light, and there are three electron guns corresponding to each of the three phosphor types.

On their own, the electrons would simply move in a straight line, all passing through the center aperture. (Which is why, for those of you old enough to remember, old TV screens would leave a white dot in the center right after you shut them off.) But inside the television, there are electromagnets, which use electricity to generate magnetic fields capable of bending electrons!

By delivering the right electrical signal to the electromagnet, you can create a magnetic field that bends these three electron beams both horizontally and vertically! A 10,000 fps high-speed camera can show you this in far greater detail than I can explain, so watch for yourself.

Either electric or magnetic fields are capable of bending electrons like this, and can do so very quickly, which is what's important here. Remember this video, because even though a single line on the screen takes just a couple of microseconds, and scanning once down the entire screen takes maybe 16 milliseconds, electric and magnetic fields can be changed very rapidly in one direction, allowing a constant beam of electrons to be bent by varying amounts over very short timescales.

So how do we get down to trillionths of a second, or picosecond resolution?

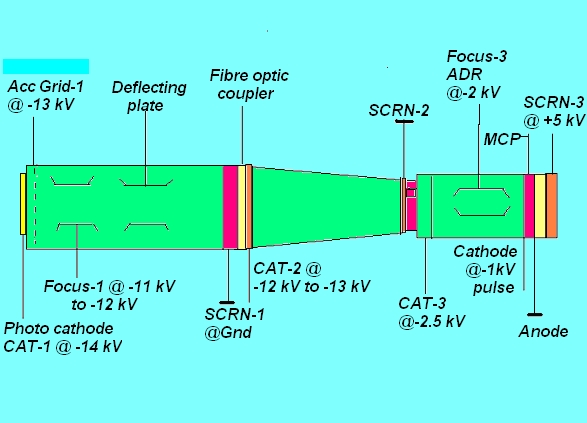

Use a streak tube! What a streak tube typically does is takes -- with incredibly high-speed resolution -- incoming photons and converts them into electrons! But even with technology like this, you can't take a picture at a trillion frames per second; the best you can do is get information-containing electrons coming in, one-after-another, separated by mere picoseconds.

So, if that's what the streak camera can give you, how can you use this information to construct a movie, say, of a single laser pulse? What they do, instead of taking a full, 2-dimensional snapshot like an ordinary camera does, is they only take a single, horizontal row of pixels into the streak camera, and apply either a changing electric or magnetic field to bend-and-separate the electrons, dependent on the arrival time. The principle is the same as a photo like this.

Rather than taking a 2-D video and smearing it out over space, like this time-lapse photo does, the streak camera uses electronics to take a 1-D video and smear it out over time into a 2-D image! In other words, rather than a picture that has the x-axis as horizontal position and y-axis as vertical position, this camera uses its electric and/or magnetic fields to have the x-axis be horizontal position and the y-axis be the smeared-out axis of time!

Although I was unable to find exactly the technical modifications were that this particular group used, this example (from this site) helps illustrate what the setup might look like.

You have a horizontally incoming line, and your changing electric field smears the image out vertically, creating a "video slice" where the earliest arriving electrons (corresponding to early times) create the bottom of the image, but the later ones create the top of the image. So that's what you'll get: a "video slice" of a 1-dimensional line and what that looks like over time. All you need to do now is take a few hundred (or maybe a thousand) of those slices, until you can piece together a video from the different slices -- or layers -- of the video!

So what they do is send out a series of very short, very regularly spaced laser pulses, and have the pulse strike the object they're trying to make the video of.

And with each pulse, you adjust your setup to get the next horizontal line up. You can't physically take a full, 2-dimensional snapshot in just a picosecond or two, but you can take a snapshot of a single line with picosecond time-resolution. If you do that -- and accurately control your timing -- a thousand times in a row, you can reconstruct the video by piling the lines atop one another, stitching a video of the separate pulses together, layer-by-individual-layer.

The end result? Well, do it properly, and you've got yourself the slowest slow-motion video ever, capable of observing what an individual object would look like when a single photon pulse is shone on it. Take a look!

Congratulations to Ramesh Raskar and his entire team on a very clever setup, amazing videos and a fantastic new technology and technique!

It's a pretty amazing world we live in where we can visualize single photon pulses as they travel through space and reflect off of objects, where we can slow it down a trillion times and see it with our own eyes. Not bad at all!

I shared this last video on my blog on the 13th. It's really incredible. I monitor news and media coming out of MIT and I've noticed they have a HORRIBLE habit of assigning ambiguous or very vague titles to their articles that convey little information concerning the content. I think their stories would get picked up a little easier if they worked on this.

On November 4th I posted a video from arXiv on slow motion video capturing of water balloons being pierced. It's got a little extra information on the fluid dynamics behind this process.

If interested, the water balloon post is at http://astronasty.blogspot.com/2011/11/hydrodynamics-wine-swirling-and…

I wouldn't say single photon pulses since you obviously have to illuminate the object the same way numerous times to produce a single image. Besides, the terminology is vague; I'd imaged single pulses over 20 years ago - it's just that the time resolution was coarse and I had an ordinary photo taken with a narrow frequency very bright flash. In other words I couldn't see the apparent propagation of light with time.

The image from "howstuffworks" is a bit weird. The mask used is the Trinitron mask (created by Sony and better known as 'aperture-grille') which has vertical slits as opposed to the triangular pattern of dots typically used in masks. The electrons of course have no color (unlike in the image) nor do the electrons for a specific color pass through the same slit - each slit has only one color phosphor behind it.

About the TV tube image, sure electons have no color but there are three beams for red, green and blue. They do all go through the same slit hitting the right one of three phosphor dots because of the angle.

Here is a link to Abramson's orighinal article using a holographic method for capturing light in flight:

http://www.opticsinfobase.org/abstract.cfm?URI=ol-3-4-121

What exactly are we seeing? What is that wave? That's not a single photon, is it?

No, it's a great many photons. Really it's just an expanding shell of light. In a more everyday setup that "wave" would just be the front line of light continually washing over the scene. Imagine turning a light source on for a tiny fraction of a second and then immediately turning it back off again: that's pretty much what you're seeing here.

Ok. But what about the wave shape fo the pulse, is that an artifact of the emitter, or does it have to do with the wave nature of photons?

As usual, an excellent blog post. My new favorite website. Thank you! - Ethan from Seattle, WA

Great post.

I love how the crack in the glass has overtaken the bullet.

Two questions:

If, instead of a slowly rotating mirror and numerous photon pulses (one for every row of pixels collected)... you had a curved mirror that re-directed the input at X number of sensors, could you not collect a moving image of X rows from a single photon pulse?

Secondly... could this technique be used to capture at a virtually arbitrary framerate? What are the limits of it?

@Dave#3: No, electrons for R G B all pass through different slits. The mask is hard up against the phosphor screen; you cannot illuminate different color phosphors from the same slit - if you could then you'd have all sorts of problems including 'bleeding'.