“It’s hard to build models of inflation that don’t lead to a multiverse. It’s not impossible, so I think there’s still certainly research that needs to be done. But most models of inflation do lead to a multiverse, and evidence for inflation will be pushing us in the direction of taking [the idea of a] multiverse seriously.” -Alan Guth

You've heard the question asked before about controversial or new-style pieces of work, "But is it art?" Well, what about the scientific counterpart of that?

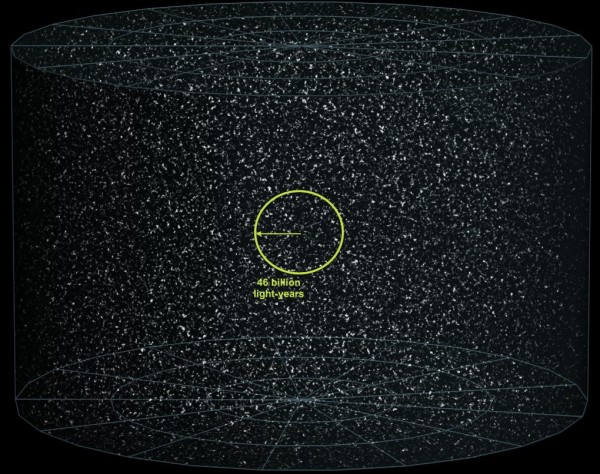

Image credit: Moonrunner Design, via http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/03/140318-multiverse-infla….

Image credit: Moonrunner Design, via http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/03/140318-multiverse-infla….

If we have an idea whose foundations are rooted in science -- that may even come about as an inevitable consequence of our best scientific understanding -- is that idea inherently scientific? Or if it fails to meet certain criteria, is it moved out of the realm of science and into... another place?

The Multiverse certainly falls into that category, so what is it?

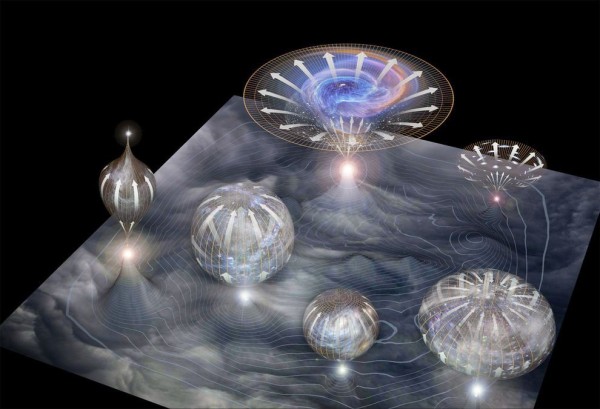

Image credit: Moonrunner Design, via http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/03/140318-multiverse-infla….

Image credit: Moonrunner Design, via http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/03/140318-multiverse-infla….

Interesting read.

Beautifully done. Thank you, Ethan.

SEems like we're stuck at both ends. Neither strings nor multiverses are experimentally accessible.

Could this be the Physics equivalent of the Göedel Incompleteness Theorem? There are true facts about the universe that can not be proven in a finite amount of time?

You might, perhaps, want to be a lmore accurate and circumspect when speaking about biology, It is wrong to say: "Darwin’s theory of evolution was a great example, superseded by genetics and then further superseded by the discovery of DNA".

The theory of evolution has been extended mechanistically through a number observations, such as how genetic information is stored and used, it has not been superseded.

Nice work.

At first (more than a few years ago) I paid no attention to the multiverse theory specifically because it appeared to be untestable. Later (last couple of years) I ended up thinking it was common sense, on the basis of an extension of "non-privileged position:" if the Earth, the solar system, and the Milky Way were each in its day found to not be at the center of the universe, then the universe itself may as well not be the center or the one-and-only. That's not exactly sound scientific reasoning, more like the process of accepting something as one becomes more familiar with it: a change in the emotional response to the idea, backfilled with retrodiction ("of course it had to be this way"). None the less, arguably not-unreasonable for laypeople.

I've read before that the multiverse theory is a logical outgrowth of cosmic inflation, but you here spelled it out clearly enough that this part now "makes sense" (again, "makes sense" in that layperson sort of way;-). So now we come to the question of whether we're quantum-entangled with other universes, also untestable within current and expected physics. None the less interesting to speculate how one might build an apparatus to detect any indication that e.g. photons are being tweaked elsewhere in an attempt to send any sort of message, even a slight skew from randomness.

As for metaphysics, good! Metaphysics that arises "bottom up" from physics, is far better than metaphysics that arises "top down" from someone's idea of what "ought" to be. "Ought" should come from "is," not vice-versa, and at risk of digression I'll say that the same case should obtain for the "oughts" of moral and ethical systems. Facts plus values should produce praxis. If we value knowledge and understanding, then the facts we presently have about the universe should impel the ongoing quest to learn more, and yes to engage in metaphysical speculations as a route to developing more inclusive theories.

Since this is controversial, let me get rid of the uncontroversial first. Like Mike already noted, it is wrong - in biologist's terms - to claim that evolution has been superseded. Biologists treats theories differently in that they are additive insteadof exclusive.

Hence classic evolution was married with Fisher's population genetics (which built on Mendel's empirics) into the "Modern Synthesis". (In the 50's I think.) Later modern genetics has been added and so on. You can't understand population genetics without evolution, and it is considered the basics of biology.

As for the controversial, it seems to me you conflate theories with well tested theories. general relativity was not any less of a theory before it was first tested with Mercury's precession and gravitational light bending?

I am going to punt on "solve", since I can't understand why predictive description wouldn't suffice by your own description of theories. Either the description is wrong (and I think not), or you are secretly inserting some criteria you haven't stated.

Is eternal inflation predictive? Not necessarily, as you have described. Is it not doable - assuming multiverses vary in properties - to predict? Weinberg showed already 1989 that it is an inherently predictive physics, it predicts the vacuum energy. Maybe that is because multiverses _do_ vary in properties, and so we have learned much about them.

I should add that I know some of biology since I have a long interest in astrobiology. But don't take my word for it: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolution#History_of_evolutionary_thought [So I see the synthesis was in the 20-30's. Always check...]

Oy. "general relativity was not any less of a theory before it was first tested with Mercury’s precession and gravitational light bending?"

Intended: General relativity was not any less of a theory before it was first tested with Mercury’s precession and gravitational light bending.

I believe that the problem with today's cosmological physics is an inaccurate and incomplete understanding of the relationship between space time and energy. The three dimensions of space, one of time and one of energy form a five dimensional manifold which existing mathematics cannot effectively model. As to this mathematical lack, let me point to Maxwell's 3rd and 4th laws which although being very successful, are mathematically incomplete. This can be determined by Maxwell having to add a term to the third law, to make it compatible with the existing mathematics. Vector algebra cannot handle equations in dimensions higher than 3. Mathematical models of the universe and physics are dependent on the mathematics chosen for the model. The worst of all mathematics to choose as a model for physics is statistics.

I think if we were to confirm a specific variant of inflationary theory to a great extent, and that variant had a multiverse as a necessary component, then we would call it confirmed. This is standard science; if you have a theory that predicts A-Z (when other theories don't), and you confirm A-Y but can't get at Z, you provisionally conclude that the theory and all its deductive conclusions are confirmed, and that includes accepting conclusion Z. At least until some other theory comes along to unseat it.

Right now, I'd say we are in the position where there are many experimentally indistinguishable variants of inflation theory. While this is not my field, AIUI, most and the strongest predict a multiverse (this is Guth's position). So as a scientist it is reasonable to provisionally conclude that one exists. However, since there are some viable flavors of inflationary theory that don't require a multiverse, it is also not irrational or completely unreasonable to conclude it doesn't.

To liken it to a horse race, there are favorites, contenders, and longshots. You're not being crazy or silly if you bet on a contender against the favorite, though if you bet on a 10,000-to-1 longshot you might rightly be called that. IMO right now an inflationary multiverse is the favorite, but there are inflationary non-multiverse contenders. A non-multiverse is not a longshot, so its not necessarily irrational to bet on it. AIUI a singular universe is not the favorite either, though, so when you bet on it you are betting against the leading form of the theory.

OK, wordsalad there.

What is it about YOUR SPECIFIC CLAIM of what energy is that makes it a dimension to place on the same level as x, y, z and t?

And why do they all make a manifold? And what do you MEAN by it?

or

Tensorial mathematics can.

Simultaneous equations can too.

Oh, and vector maths too. Given that a vector is just a line to modify in a matrix analysis and must be expanded to cover more than two dimensions to get to three dimensions, therefore can be expanded likewise to three.

No vectors past three dimensions? Does that mean my time learning about Hilbert space and functional analysis was wasted?

Let me guess, "PE" stands for 'professional engineer,' doesn't it?

"The worst of all mathematics to choose as a model for physics is statistics."

Good grief .

"It means that the Multiverse — assuming that our current picture of the Universe and its history is valid — is probably real ...... But it also means it’s beyond the realm of testability, even in principle."

Aren't these two statements contradictory?

Any kind of scientific test amounts an assignment of probability to the hypothesis in question - an evaluation of the evidence in its favour. If you can say that a thing is probably real, then its existence has already passed some kind of test.

If by 'scientific test' one means something that will return a definitive answer - an immutable P = 0 or P = 1 - then I suspect only a couple of seconds of reflection are enough to realize one's mistake. So what we are necessarily left with as the only option is a probability assignment (or something that serves as a reasonable approximation).

No. Popperian falsifiability is a decent yardstick of what is validly science, but it isn't the sole determinant of what can be scientific.

Wow,

Actually, a non-falsifiable theory amounts to one with infinite degrees of freedom, which, as I explain here, has the consequence that no amount of evidence can raise its associated probability above zero.

For this reason, falsifiability is a necessary condition for a proposition to be considered scientific.

What 'testability' really means, is that we can gather and process evidence that can potentially change our probability assignment. It is fundamentally necessary for science to proceed. See, for example (both by me), Inductive inference or deductive falsification? and The Calibration Problem: Why Science Is Not Deductive.