Experiment

Element: Cesium (Cs)

Atomic Number: 55

Mass: One stable isotope, mass 133 amu.

Laser cooling wavelength: 854nm, but see below.

Doppler cooling limit: 125 μK.

Chemical classification: Yet another alkali metal, column I of the periodic table.

This one isn't greyish, though! It's kind of gold color. Still explodes violently in water, though.

Other properties of interest: The definition of the second in the SI system of units is in terms of the microwave transition between hyperfine ground states in Cs-- 9,192,631,770 oscillations to one second, to be precise. Has a really large scattering…

Element: Chromium (Cr)

Atomic Number: 24

Mass: Four "stable" isotopes between 50 and 54 amu. Chromium-50 is technically radioactive, with a half-life considerably longer than the age of the universe, so...

Laser cooling wavelength: 425nm, but see below.

Doppler cooling limit: 120 μK.

Chemical classification: Transition metal, smack in the middle of the periodic table. Shiny.

Other properties of interest: Has a fairly large magnetic moment in its ground state, 6 Bohr magnetons, which means it has strong magnetic interactions. For this reason, it's kind of an interesting system to study-- you…

Element: Lithium (Li)

Atomic Number: 3

Mass: Two stable isotopes, masses 6 and 7 amu

Laser cooling wavelength: 671 nm

Doppler cooling limit: 140 μK.

Chemical classification: Alkali metal, column I in the periodic table. Yet another greyish metal. We're almost done with alkalis, I promise. Less reactive than any of the others, so the explosions in water aren't very impressive.

Other properties of interest: Lithium-7 is a boson, but has a negative scattering length, meaning that BEC's of lithium-7 tend to implode unless you modify the collisional properties. Lithium-6 is a fermion, and much…

Element: Francium (Fr)

Atomic Number: 87

Mass: Numerous isotopes ranging in mass from 199 amu to 232 amu, none of them stable. The only ones laser cooled are the five between 208 amu and 212 amu, plus the one at 221 amu.

Laser cooling wavelength: 718 nm

Doppler cooling limit: 182 μK.

Chemical classification: Alkali metal, column I in the periodic table. The heaviest known alkali, it's presumably metallic in appearance, if you could ever get enough of it together to look at.

Other properties of interest: Francium has no stable isotopes, and the longest lifetime of any of its isotopes is around…

Element: Strontium (Sr)

Atomic Number: 38

Mass: Four stable isotopes, ranging from 84 to 88 amu

Laser cooling wavelength: Two different transitions are used in the laser cooling of strontium: a blue line at 461 nm that's an ordinary sort of transition, and an exceptionally narrow "intercombination" line at 689 nm.

Doppler cooling limit: 770 μK for the blue transition, below a microkelvin for the red. The Doppler limit for the red line turns out not to be all that relevant, as other factors significantly alter the cooling process.

Chemical classification: Alkaline earth, column II of the…

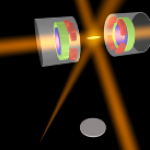

When I wrote up the giant interferometer experiment at Stanford, I noted that they've managed to create a situation where the wavefunction of the atoms passing through their interferometer contains two peaks separated by almost a centimeter and a half. This isn't two clouds of atoms each definitely in a particular position, mind, this is a wavefunction representing a bunch of atoms that are each partly in two places at the same time , separated by 1.4 centimeters.

I emailed Mark a link to the post, and in his reply he said that they've increased that to about 4cm (which is just a matter of…

Element: Xenon (Xe)

Atomic Number: 54

Mass: nine "stable" isotopes, masses from 124 to 136 amu. Xenon-136 is technically radioactive, but with a half-life of a hundred billion billion years, so, you know, it's pretty much stable.

Laser cooling wavelength: 882 nm

Doppler cooling limit: 120 μK

Chemical classification: Noble gas, part of column VIII of the periodic table. Doesn't react with anything, so poses much less danger to scientists than any of the alkalis, though it has, at times, been used as an anesthetic, and Will Happer's group at Princeton has a funny story about a student's…

Element: Helium (He)

Atomic Number: 2

Mass: two stable isotopes, 3 and 4 amu.

Laser cooling wavelength: 1083 nm

Doppler cooling limit: 38 μK

(It should be noted, though, that despite the low temperature, laser-cooled helium has a relatively high velocity-- that Doppler limit corresponds to an average velocity that's just about the same as for sodium at 240 μK. This is because temperature is a measure of kinetic energy, and helium is much, much lighter than any of the other laser-cooled elements.)

Chemical classification: Noble gas, part of column VIII of the periodic table. Doesn't react with…

I'm writing a bit for the book-in-progress about neutrinos-- prompted by a forthcoming book by Ray Jaywardhana that I was sent for review-- and in looking for material, I ran across a great quote from Arthur Stanley Eddington, the British astronomer and science popularizer best known for his eclipse observations that confirmed the bending of light by gravity. Eddington was no fan of neutrinos, but in a set of lectures about philosophy of science, later published as a book, he wrote that he wouldn't bet against them:

My old-fashioned kind of disbelief in neutrinos is scarcely enough. Dare I…

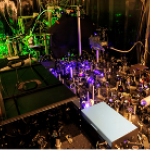

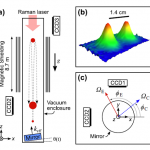

A little over a year ago, I visited Mark Kasevich's labs at Stanford, and wrote up a paper proposing to use a 10-m atom interferometer to test general relativity. Now, that sounds crazy, but I saw the actual tower when I visited, so it wasn't complete nonsense. And this week, they have a new paper with experimental results, that's free to read via this Physics Focus article. Which might seem to make me blogging it redundant, but I think it's cool enough that I can't resist.

OK, dude, "Multiaxis Inertial Sensing with Long-Time Point Source Atom Interferometry" is not the sexiest title in the…

Element: Rubidium (Rb)

Atomic Number: 37

Mass: two "stable" isotopes, 85 and 87 amu (rubidium-87 is technically radioactive, but it's half-life is 48 billion years, so it might as well be stable for atomic physics purposes.

Laser cooling wavelength: 780 nm

Doppler cooling limit: 140 μK

Chemical classification: Alkali metal, column I of the periodic table. Like the majority of elements, it’s a greyish metal at room temperature. Like the other alkalis, it’s highly reactive, and bursts into flame on contact with water, even more so than sodium (in general, the alkalis get more violently reactive…

Element: Sodium (Na)

Atomic Number: 11

Mass: one stable isotope, 23 amu

Laser cooling wavelength: 589 nm

Doppler cooling limit: 240 μK

Chemical classification: Alkali metal, column I of the periodic table. Like the majority of elements, it's a greyish metal at room temperature. Like the other alkalis, it's highly reactive, and bursts into flame on contact with water. For this reason, all physicists working with sodium have True Lab Stories about accidentally blowing stuff up with it.

Other properties of interest: Scattering length of around 80 a0; Feshbach resonance at around 900 G.

History:…

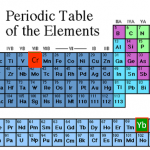

At the tail end of the cold-atom toolbox series, I joked about doing a "trading card" version shortening the posts to a more web-friendly length. In idly thinking about this, though, it occurred to me that if one were going to have cold-atom trading cards, it might make more sense to have them for the atoms, rather than the techniques. And having just devoted many thousands of words to technique, I don't really feel like trying to cut those down more, but atoms...

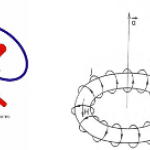

The "featured image" up top is a slide from my laser cooling lectures for our first-year seminar class. Elements outlined in red…

This is probably the last trip into the cold atom toolbox, unless I think of something else while I'm writing it. But don't make the mistake of assuming it's an afterthought-- far from it. In some ways, today's topic is the most important, because it covers the ways that we study the atoms once we have them trapped and cooled.

What do you mean? They're atoms, not Higgs bosons of something. You just... stick in a thermometer, or weigh them, or something... OK, actually, I have no idea. They're atoms, yes, but at ultra-low temperatures and in very small numbers. You can't bring them into…

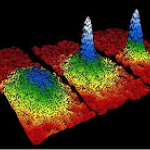

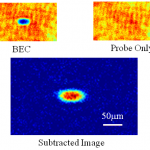

In our last installment of the cold-atom toolbox series, we talked about why you need magnetic traps to get to really ultra-cold samples-- because the light scattering involved in laser cooling limits you to a temperature that's too high for making Bose-Einstein condensation (BEC). This time out, we'll talk about how you actually get to those ultra-cold temperatures.

What do you mean? I assumed it was just part of the trapping process? No, because the forces involved in magnetic trapping are like those involved in optical dipole traps. In physics jargon, they're "conservative" forces, which…

We're getting toward the end of the cold-atom technologies in my original list, but that doesn't mean we're scraping the bottom of the barrel. On the contrary, the remaining tools are among the most important for producing and studying truly ultra-cold atoms.

Wait, isn't what we've been talking about cold enough? There is, as always, more art than science in the naming of categories of things. "Cold" and "ultra-cold" get thrown around a lot in this business, and the dividing line isn't quite clear. Very roughly speaking, most people these days seem to use "cold" for the microkelving scale…

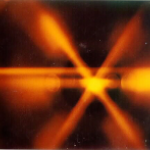

Today's dip into the cold-atom toolbox is to explain the real workhorse of cold-atom physics, the magneto-optical trap. This is the technology that really makes laser cooling useful, by letting you collect massive numbers of atoms at very low temperatures and moderate density.

Wait a minute, I thought we already had that, with optical molasses? Doesn't that make atoms really cold and stick them in space? Molasses does half the job, making the atoms really cold, but it doesn't actually confine them. The photon scattering that gives you the cooling force and Doppler cooling limit produces a "…

This topic is an addition to the original list in the introductory post for the series, because I had thought I could deal with it in one of the other entries. Really, though, it deserves its own installment because of its important role in the history of laser cooling. Laser cooling would not be as important as it is now were it not for the fact that cooling below the "Doppler limit" in optical molasses is not only possible, but easy to arrange. That's thanks to the "Sisyphus cooling" mechanism, the explanation of which was the main reason Claude Cohen-Tannoudji got his share of the 1997…

I spent an hour or so on Skype with a former student on Tuesday, talking about how physics is done in the CMS collaboration at the Large Hadron Collider. It's always fascinating to get a look at a completely different way of doing science-- as I said when I explained my questions, the longest author list in my publication history doesn't break double digits. (I thought there was a conference proceedings with my name on it that got up to 11 authors, but the longest list ADS shows is only eight). It was a really interesting conversation, as was my other Skype interview with a CMS physicist.…

Last time in our trip through the cold-atom toolbox, we talked about light shifts, where the interaction with a laser changes the internal energy states of an atom in a way that can produce forces on those atoms. This allows the creation of "dipole traps" where cold atoms are held in the focus of a laser beam, but that's only the simplest thing you can use light shifts for. One of the essential tools of modern atomic physics is the "optical lattice," which uses patterns of light to make patterns of atoms.

OK, what do you mean "patterns of light"? Well, remember, light has both wave and…