Two Cultures

Writing for the Internet is like yelling into the void: freeing, probably more than a little cathartic, but ultimately lonely. That's not to say that I haven't made profound connections out here, but like most writers I long for a little thing with my name on it that fits in the hand, that can be passed around and earmarked, tossed away and re-discovered.

Which is why I'm so pleased to announce the existence of precisely such a little thing: my brand-new collection of essays and arcana, High Frontiers, fresh from the presses of Publication Studio:

High Frontiers brings together…

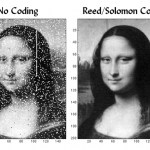

The cultural critic Walter Benjamin, in his seminal 1936 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, argued that the "aura" of a work of art, that sense of special awe and reverence we feel, being in its presence, isn't inherent to art itself. Rather, it's a side-effect of its exclusivity, restricted exhibition, authenticity, or perceived value. With the age of "mechanical reproduction" (i.e. printed copies, films, and photographs), that aura disappeared, freeing art from its ties to the bourgeoisie and allowing mass audiences to, in a sense, "own" the work too. Take the Mona…

"This one will look like a jellybean," the session director warns us. "Or, you know, when you empty a hole punch? The circles of paper that fall out? One of those." She's talking about Neptune, and I am about to step, carefully, up a ladder painted industrial yellow and wheeled into place in front of the centenarian eyepiece of the 60" Hale telescope at Mt. Wilson Observatory, incidentally the very place where Edwin Hubble, in 1925, discovered that our galaxy was not the entirety of the Universe, and later, that our Universe was expanding.

A jellybean, a piece of confetti: it seems her…

I probably don't need to introduce Oliver Sacks to you. You've undoubtedly already delighted over his wobbly affectation and tales of neurological strangeness on RadioLab or NPR. You might have read his lovely first-person account, in the New Yorker, of his early experiments with hallucinogens of all stripes, from the "pharmacological launch pad" of amphetamines and LSD, to the synthetic belladonna-like drug, artane. You may even have read one of his bestselling books of clinical studies, like The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat or Awakenings.

I interviewed Dr. Sacks in 2007, on the…

To scientists, "experimental" is a technical word, one with a precise meaning: that which relates to a procedure of methodical trial and error, to a systematic test for determining the nature of reality. I got in trouble on this blog once, with commenters, for using the word "experimental" too flippantly.

But artists experiment too, of course. Their method of inquiry is different, free from the rigidity that characterizes the scientific method. Artistic experiments are designed to be singular; they aren't supposed to be repeated. They have no control variables. Often, even the…

Last week, I wrote a piece for Motherboard about an android version of the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick. The story of the android is truly surreal, stranger than even Dick's flipped-out fiction, and I recommend you pop over to Motherboard and mainline it for yourselves. For the piece, I interviewed the lead programmer on the first version of the PKD Android, Dr. Andrew Olney. Aside from bringing science fiction legends back from the dead, Olney is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Memphis and Associate Director of the same university's…

"I read this book. It's pretty good even if they made it in a week. Worth the fifty bucks, easy."

Bruce Sterling

In February of this year, I had the distinct pleasure of being invited to the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, a zygote of an institution nestled between departments at Carnegie Mellon University, to work on a strange collaborative project called a "booksprint." A booksprint, I discovered, is a fairly new practice, derived from the world of open-source software "codesprints." In this version, a group of writers work exhaustively for a week on a shared project, which is then made…

Ed: This is an essay I wrote for my friends at the World Science Festival, riffing on the central themes of this years' event. If you prefer, you can also read this piece on the World Science Festival site. And, if you're in New York between the first and fifth of June, you could do much worse than popping into the Festival and getting a load of panel discussions like The Dark Side of the Universe, or Science & Story: The Art of Communicating Science Across All Media.

Science communication is difficult.

It can be crippled by the complexity of its own subject matter. It can be steeped in…

The moon is a rock.

But it's also Selene, Artemis, Diana, Isis, the lunar deities; an eldritch clock by which we measure our growth and fertility; home of an old man in the West and a rabbit in the East; the site of countless imaginary voyages; a long-believed trigger of lunacy (luna...see?). It's another world, close enough to our to peer down at us; to it, we compose sonatas. It can be blue, made of cheese, a harvest moon; we've long fantasized about its dark side, perhaps dotted with black monoliths or inhabited by flying men.

The moon is a totem of great importance in all religions…

This is the first in a series of posts about art, the moon, and art on the moon. You would think this would be a fairly limited subject, but...

Art on the moon has been happening for a long time.

In 1969, a coterie of American contemporary artists devised a plan to put an art museum on the Moon. When NASA's official channels proved too dauntingly bureaucratic, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, David Novros, Forrest "Frosty" Myers, Claes Oldenburg, and John Chamberlain weren't deterred. Instead, they managed to sneak their "museum" -- in reality a minuscule enamel wafer inscribed with six…

In 2007, my friends at m ss ng peces and I started work on a new Internet-television show called RESET, for the Sundance Channel. The idea was to make a show designed for computers to watch, that could teach them what it was like to be human -- a show that, while ostensibly made for human beings, would also nourish our computers' circuit boards with generous descriptions of the richness of human experience. Obviously this is just an artistic conceit, and not, as far as I know, a practicable reality, but it does raise a lot of interesting questions. You probably spend your entire day within…

To prepare for a "Book Sprint" I'm participating in at the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry at Carnegie-Mellon University next week, I've been doing lots of research about notable historical interactions between art, science, and technology. In suit, Universe fringe benefits!

First, I'd like to tell you about "9 Evenings," organized in 1966 by a very interesting engineer named Billy Klüver with the help of the great American artist, Robert Rauschenberg.

Klüver is a fascinating character, a brilliant engineer who saw the potential in the integration of art and technology, and noticed an absence…

We live in an age where truth is, if not stranger than fiction, then at least equally strange. Sometimes pop-science books illustrate this point with particular well-researched glee and Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void is such a book.

Where do I begin? It's a true nerd's smorgasbord. It answers all the scatological and emotional questions that kids always imprudently ask astronauts. It acknowledges the humanness of space travel as a venture: that astronauts are people who must eat, pass gas, have sex, take up space, sweat, sleep, fear, and otherwise learn to be…

A few months ago, I attended Cyborg Camp in my hometown of Portland, Oregon. Cyborg Camp is an "unconference," basically a room full of cyberpunks, mega-nerds, and aspirational coders that gather in an office building to talk about the "future of the relationship between humans and technology." This event deserves a separate entry, but for now I'd like to recall a particularly evocative thing: that the most heartbreaking thing I saw at Cyborg Camp was an adult man hopelessly tangled in a web of cables.

It was his own off-the-shelf wearable computing system, a gordian thing connecting his…

Let's talk about the God Particle.

It strikes me that people refer to the Higgs boson as the "God particle" in the same way some call the iPhone the "Jesus phone": with an almost pointed disregard for what such a prefix actually means. Considering the intensity of the culture wars, the popularity of the moniker is baffling. Is this about contextualizing the abstraction (and grandeur) of particle physics in a way "regular" people can understand? Does this represent a humanist concession to the religious? If so, can religious culture really be swayed by such a transparent ploy -- y'know, it…

I believe the world is a complex phenomenological experience that can be explained, rationalized, and lived in myriad different ways. The way I see it, we all begin with the same fundamental mystery -- why are we here? what is life? -- and we attack this problem with whatever tools we find work best; some of us use science, parsing and decoding the secrets of life with a toolbox of methods and reason. Others, with the same goals in mind, use art, arranging ideas and objects in intentional ways designed to root at the questions of existence. Others still depend on the framework of religion to…

If it has always been your fantasy to send your physical likeness out into the cosmos, now is your time! To commemorate the final two Shuttle missions, NASA has created a bonkers "Face in Space" initiative, which allows you to upload a picture of yourself to send to the International Space Station. What this actually entails, I imagine, is a burned data DVD in an astronaut's backpack -- nominal space travel if I've ever heard of it.

It's fun, and my face is already destined to launch on September 16th on STS-133; but, seriously, what is this about? Rousing public interest in the space…

A large part of my affection for science comes from the thrill of terror I get when a particularly insane piece of science news hits the presses. When an article begins with a sentence like, "there is something strange in the cosmic neighborhood," or "all the black holes found so far in our universe may be doorways into alternate realities," my pulse quickens and a dormant paranoia is roused from deep within my breast: a sensation of joyful panic. I used to call this the "fourth-grade nightmare fantasy." This might be because as a long-time science fiction adept, I tend to read science news…

I'm flying out to New York City on Sunday to participate in the very exciting BRAINWAVE series at the Rubin Museum of Art. BRAINWAVE, which is in its third year, brings thinkers from different disciplines to sit down with scientists to wrap their (and our) minds around the things that matter. Past pairings include Composer Philip Glass and astronomer Greg Laughlin, screenwriter Charlie Kaufman and physicist Brian Greene, and performance artist Laurie Anderson with astrophysicist Janna Levin. Needless to say, it's a fascinating series, and I'm honored to be involved.

I'll be talking with…

A couple of years ago, I was poking around in a European art museum and came across an exhibit of exquisitely beautiful Eastern Orthodox religious paintings, "icons." Beyond being visually striking -- they have an austere, hieratic, distant quality -- they are also, I realized at the time, in a way, scientific.

Alright, I know, that's a wild statement. But hear me out.

A religious icon is more than a painting. It has a semiotic value that's highly codified, a language and practical purpose of its own that sets it apart from all the other representational art preceding our modern era of…